Accessibility of Croatian Public and Private University Websites Home Pages

Valentina Kirinić1, Predrag Oreški21 University of Zagreb Faculty of Organization and Informatics 2 University of Zagreb Faculty of Teacher Education |

|

Digitalne obrazovne tehnologije |

Preliminary communication |

Abstract |

|

The provisions of the Act on the Accessibility of Websites and Software Solutions for Mobile Devices of Public Sector Bodies (Official Gazette 17/19, September 23rd, 2019) determine “measures to ensure the accessibility of websites and software solutions for mobile devices of public sector bodies to users, especially persons with disabilities.” The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) require that information or user interface components must be presented to users in such a way that they can perceive them. It is a legal but also a moral obligation of all web content creators which must be fulfilled in order to ensure accessibility to all users. This paper presents an analysis of the website accessibility of Croatian public and private universities with the aim of achieving, improving and promoting web accessibility and digital inclusion. The research sample consists of 9 public and 3 private Croatian universities’ websites home pages. Several tools are used to analyse their accessibility. In the research presented, methods of analysis, experiment, descriptive statistics and synthesis have been used. The results of checking the accessibility of Croatian public and private universities’ websites home pages, classification and ranking of the most common problems regarding web accessibility, i.e. non-compliance with WCAG, and guidelines to improve the accessibility of the web content have been stated. The analysis shows that the most common discrepancies are: lack of alternative descriptions of images, lack of discernible link names and inadequate colour contrast. The authors conclude that it is important to promote web accessibility in order to improve digital inclusion in education and that all stakeholders creating web content or user interface components contribute to this. |

|

Key words

|

|

accessibility check tools; digital inclusion; special needs; accessibility improvement; higher education |

Introduction

The number of students in higher education with a known disability is increasing, state Hubble and Bolton in their briefing paper (Hubble & Bolton, 2021, p. 3). In the paper it is emphasized that according to the data Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) collects on disabilities that students have, in 2019/20 332,300 (17.3%) home students in the UK said they had a disability of some kind, which is an increase of 47% compared to 2014/15. The situation is similar in Croatia (Kiš-Glavaš, 2016, p. 3).

According to the „National Strategy for Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities 2021 – 2027 of Republic of Croatia“ draft document (Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy & Ministry of Defence, 2021) there are public policy priorities which refer to achieving equal participation of persons with disabilities in higher education:

1st Priority: Inclusive upbringing and education and employment of persons with disabilities, and

3rd Priority: Ensuring the accessibility of basic social infrastructure and the content of public life, and strengthening security in crisis situations, which means accessibility of: physical environment, transport, and information and communication, including information and communication technologies and systems of other content and services open or intended for the public.

Since we literally live online, the need to check the accessibility of Croatian public and private university websites has emerged as one of the global and obvious indicators of the wider inclusion of children / students with disabilities and the inclusivity of Croatian higher education.

Web accessibility is undoubtedly something that must be ensured in every aspect of our (digital) life. According to the Web Accessibility Initiative (Web Accessibility Initiative - WAI, 2021) web accessibility means that websites, tools, and technologies are designed and developed so that people with disabilities can use them, specifically, people can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web as well as contribute to the Web. Web accessibility encompasses all disabilities that affect access to the web, including: auditory, cognitive, neurological, physical, speech and visual ones. It has to be emphasized that web accessibility also benefits people without disabilities, such as those using mobile phones, smart watches, smart TVs, and other devices with small screens, different input modes, etc., older people with changing abilities due to ageing, people with “temporary disabilities” such as a broken arm or lost glasses, people with “situational limitations” such as in bright sunlight or in an environment where they cannot listen to audio, people using a slow Internet connection, or who have limited or expensive bandwidth (Web Accessibility Initiative - WAI, 2021).

In general, accessibility of websites is regulated primarily by Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (W3C, 2022a) published also as an ISO/IEC standard ISO/IEC 40500:2012 Information Technology — W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (ISO/IEC, 2012)), as well as other standards and technical specifications provided by W3C (W3C, 2022b).

There is also a harmonised European standard - ETSI, CEN, CENELEC standard EN 301 549 V3.2.1 Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services (ETSI, CEN & CENELEC, 2021) focusing on broader aspects of digital/ICT accessibility. In Croatia, web accessibility is regulated by the Act on the Accessibility of Websites and Software Solutions for Mobile Devices of Public Sector Bodies (Hrvatski sabor, 2019).

However, WCAG is recognised as the basic document to define accessibility principles - 4 principles (W3C, 2022c) as follows:

“Perceivable - Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive.

This means that users must be able to perceive the information being presented (it can't be invisible to all of their senses)

Operable - User interface components and navigation must be operable.

This means that users must be able to operate the interface (the interface cannot require interaction that a user cannot perform)

Understandable - Information and the operation of the user interface must be understandable.

This means that users must be able to understand the information as well as the operation of the user interface (the content or operation cannot be beyond their understanding)

Robust - Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies.

This means that users must be able to access the content as technologies advance (as technologies and user agents evolve, the content should remain accessible)”.

The examples of Accessibility Principles are as follows (W3C, 2022d):

“Perceivable information and user interface

Text alternatives for non-text content

Text alternatives are equivalents for non-text content.

Examples include:

-

-

-

-

- Short equivalents for images, including icons, buttons, and graphics

- Description of data represented on charts, diagrams, and illustrations

- Brief descriptions of non-text content such as audio and video files

- Labels for form controls, input, and other user interface components

-

-

-

Text alternatives convey the purpose of an image or function to provide an equivalent user experience. For instance, an appropriate text alternative for a search button would be “search” rather than “magnifying lens”.

Text alternatives can be presented in a variety of ways. For instance, they can be read aloud for people who cannot see the screen and for people with reading difficulties, enlarged to custom text sizes, or displayed on braille devices. Text alternatives serve as labels for controls and functionality to aid keyboard navigation and navigation by voice recognition (speech input). They also act as labels to identify audio, video, and files in other formats, as well as applications that are embedded as part of a website.”

Methodology

Aims

This paper presents an analysis of the website home page accessibility of Croatian public and private universities with the aim of achieving, improving and promoting web accessibility and digital inclusion. The results of analysis would show the state of the art of web accessibility in HEIs - institutions that should be leaders in practising and promoting web/digital accessibility and digital inclusion.

The analysis aims to answer the question whether all Croatian public and private universities websites home pages comply with web accessibility guidelines stated in WCAG.

Methods and Instruments

The research sample consists of 9 public and 3 private Croatian universities’ websites home pages. Several software tools are used to analyse their accessibility. In the research presented, methods of analysis, experiment, descriptive statistics and synthesis have been used.

Three software tools chosen for the accessibility analysis are from the Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool List (https://www.w3.org/WAI/ER/tools/) and analyse the web content according to WCAG 2.0 and WCAG 2.1:

- Google Lighthouse - https://developers.google.com/web/tools/lighthouse/ (WCAG 2.0)

- TAWDis - https://www.tawdis.net (WCAG 2.0)

- Accessibility Checker - https://www.accessibilitychecker.org/ (WCAG 2.1)

They are chosen as they are free, easy to use as an online web service or install as a web browser extension.

The 9 public and 3 private Croatian universities’ websites have been checked by all three tools under the same conditions at the same time (January, 2022).

Web Accessibility Tools

Three web accessibility analysis tools present its findings on different levels of detail.

Lighthouse gives a compliance index and a list of found issues (i.e. non-compliances with WCAG), mentioning them only once regardless of the number of actual occurrences on the analysed website. An example of a website accessibility analysis result obtained from this software tool is as follows:

“Accessibility - 95

CONTRAST

Background and foreground colors do not have a sufficient contrast ratio.

These are opportunities to improve the legibility of your content.

NAMES AND LABELS

Links do not have a discernible name

These are opportunities to improve the semantics of the controls in your application. This may enhance the experience for users of assistive technology, like a screen reader.”

Lighthouse tests the website for performance, best practices, SEO (Search Engine Optimization), and PWA (Progressive Web App) as well.

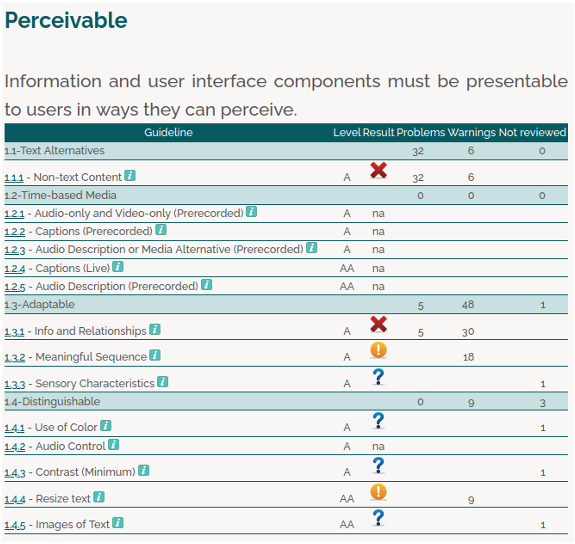

TAWdis lists and counts its findings in more detail, guideline by guideline. There is a total number of problems found, and the tool classifies them on the success criteria type (Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, Robust). A part of a website accessibility analysis result is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A part of a website accessibility analysis by TAWdis software tool

The Accessibility Checker software tool gives the score (from 0 to 100), and gives a number and a list of different issues classified as urgent or secondary (in percentage as well). Score of 95 and over means that the website is compliant with WCAG accessibility criteria. An example of a website accessibility analysis result is as follows:

“Status: NOT COMPLIANT

Score: 38

Urgent Issues: 2 (7%)

Secondary issues: 24 (86%)

Passed elements: 2 (7%)

Urgent issues (2):

Visual & motor - Document Doesn’t Have A <title> Element

Visual issue - <html> element does not have a [lang] attribute

Secondary issues: 24 (86%)

Visual issue - Custom controls have ARIA roles, [aria-*] attributes do not match their roles

Visual issue - [aria-hidden='true'] elements contain focusable descendants

Visual issue - ARIA items do not have accessible names

Visual issue - [role]s do not have all required [aria-*] attributes

Visual issue - Elements with an ARIA [role] that require children to contain a specific [role] are missing some or all of those required children

Visual issue - [role]s are not contained by their required parent element

Visual issue - [role] values are not valid

Visual issue - [aria-*] attributes do not have valid values

Visual issue - [aria-*] attributes are not valid or misspelled

Visual issue - <dl>s do not contain only properly ordered <dt> and <dd> groups, <script>, or <template> elements

Visual issue - Definition list items are not wrapped in <dl> elements

Visual issue - [id] attributes on active, focusable elements are not unique

Visual issue - ARIA IDs are not unique

Visual issue - Form fields have multiple labels

Visual issue - <input type='image'> elements do not have [alt] text

Visual issue - Presentational <table> elements do not avoid using <th>, <caption>, or the [summary] attribute

Visual issue - Lists do not contain only <li> elements and script supporting elements (<script> and <template>)

Visual issue - List items (<li>) are not contained within <ul> or <ol> parent elements

Cognitive issue - The document uses <meta http-equiv='refresh'>

Visual issue - Cells in a <table> element that use the [headers] attribute refer to an element ID not found within the same table

Visual issue - <th> elements and elements with [role='columnheader'/'rowheader'] do not have data cells they describe

Visual issue- [lang] attributes do not have a valid value

Visual issue - <video> elements do not contain a <track> element with [kind='captions']

Auditory - <video> elements do not contain a <track> element with [kind='description']

Passed audits: (2)

Visual issue - `[aria-hidden="true"]` is not present on the document `<body>`

Visual issue - Background and foreground colors have a sufficient contrast ratio”

Results and Discussion

The results of the web accessibility checking of Croatian public and private universities’ websites home pages, classification and ranking of the most common problems regarding web accessibility, i.e. non-compliance with WCAG, and guidelines to improve the accessibility of the web content have been stated. Table 1. shows the summary of anonymized web accessibility analysis data which were obtained by using the three web accessibility analysis tools. Detected issues are not written here in order to save space but for the Lighthouse they are stated in Table 2 as a ranked summary for all websites.

Table 1.

Summary of anonymized web accessibility analysis data using three web accessibility analysis tools

|

|

Accessibility Analysis Tools |

||

|

Website number |

Lighthouse | Tools for Web Developers WCAG Compliance Index(max. 100), Set of Issues that can be automatically detected (some presented in the Table 3) |

TAWdis Total number of issues, number of issues by success criteria |

Accessibility Checker Score (max. 100), Urgent issues and Secondary issues (number and %) |

|

1 |

73 |

117 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 37 Operable 25 Understandable 3 Robust 52 |

Score: 38 Urgent Issues: 2 (7%) Secondary issues: 24 (86%) |

|

2 |

77 |

69 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 14 Operable 23 Understandable 4 Robust 28 |

Score: 44 Urgent Issues: 10 (31%) Secondary issues: 19 (60%) |

|

3 |

(unfinished test) |

42 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 12 Operable 25 Understandable 2 Robust 3 |

Score: 0 Urgent Issues: 4 (13%) Secondary issues: 12 (38%) |

|

4 |

89 |

163 Problems in 6 success criteria Perceivable 60 Understandable 24 Robust 34 |

Score: 61 Urgent Issues: 2 (6%) Secondary issues: 14 (40%) |

Table 1.

Summary of anonymized web accessibility analysis data using three web accessibility analysis tools (cont.)

|

|

Accessibility Analysis Tools |

||

|

Website number |

Lighthouse | Tools for Web Developers WCAG Compliance Index(max. 100), Set of Issues that can be automatically detected (some presented in the Table 3) |

TAWdis Total number of issues, number of issues by success criteria |

Accessibility Checker Score (max. 100), Urgent issues and Secondary issues (number and %) |

|

5 |

85 |

94 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 67 Operable 14 Understandable 3 Robust 10 |

Score: 58 Urgent Issues: 3 (33%) Secondary issues: 12 (33%) |

|

6 |

86 |

163 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 33 Operable 53 Understandable 4 Robust 73 |

Score: 95 (compliant!) Urgent Issues: 0 Secondary issues: 16 (44%) |

|

7 |

80 |

44 Problems in 4 success criteria Perceivable 15 Operable 20 Understandable 0 Robust 9 |

Score: 59 Urgent Issues: 4 (11%) Secondary issues: 10 (28%) |

|

8 |

95 |

31 Problems in 6 success criteria Perceivable 6 Operable 4 Understandable 1 Robust 20 |

(unfinished test) |

|

9 |

73 |

139 Problems in 7 success criteria Perceivable 56 Operable 35 Understandable 9 Robust 39 |

Score: 37 Urgent Issues: 5 (15%) Secondary issues: 13 (39%) |

|

10 |

84 |

54 Problems in 6 success criteria Perceivable 5 Operable 24 Understandable 2 Robust 23 |

Score: 56 Urgent Issues: 5 (14%) Secondary issues: 13 (35%) |

Table 1.

Summary of anonymized web accessibility analysis data using three web accessibility analysis tools (cont.)

|

|

Accessibility Analysis Tools |

||

|

Website number |

Lighthouse | Tools for Web Developers WCAG Compliance Index(max. 100), Set of Issues that can be automatically detected (some presented in the Table 3) |

TAWdis Total number of issues, number of issues by success criteria |

Accessibility Checker Score (max. 100), Urgent issues and Secondary issues (number and %) |

|

11 |

75 |

122 Problems in 6 success criteria Perceivable 11 Operable 18 Understandable 1 Robust 92 |

Score:56 Urgent Issues: 5 (14%) Secondary issues: 13 (36%) |

|

12 |

75 |

76 Problems in 6 success criteria Perceivable 21 Operable 36 Understandable 3 Robust 16 |

Score: 45 Urgent Issues: 5 (14%) Secondary issues: 17 (47%) |

All of the tools stated in Table 1 are very useful in terms of analysing websites and showing website accessibility non-compliance issues (at least those that can be automatically detected).

Table 2 lists the most common web accessibility non-compliance problems found in the web accessibility analysis of 12 university websites using the Lighthouse tool and ranked by the number of websites that are affected. The most common discrepancies are: links do not have a discernible name, background and foreground colours do not have a sufficient contrast ratio, image elements do not have [alt] attributes, and heading elements are not in a sequentially-descending order. All of these discrepancies can be fixed easily and can be easily avoided in the future web page’s design.

Table 2 mentions Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA), “Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) is a set of attributes that define ways to make web content and web applications (especially those developed with JavaScript) more accessible to people with disabilities. It supplements HTML so that interactions and widgets commonly used in applications can be passed to assistive technologies when there is not otherwise a mechanism. For example, ARIA enables accessible navigation landmarks in HTML4, JavaScript widgets, form hints and error messages, live content updates, and more.” (Mozilla, 2022)

Regarding the results presented, it should be emphasised that there are tools that can help web designers in their work by detecting web accessibility non-compliance and offering warnings that show that some of the WCAG guidelines demands are not met.

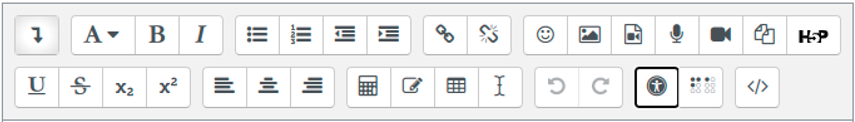

The web page accessibility check is present as an option/button in the popular text editors such as one in Learning Managements System (LMS) MOODLE, which can check the accessibility of edited web content (Figure 2).

Table 2. The ranked problems regarding web accessibility found on 12 websites analysed using the Lighthouse tool with the number and percentage of websites affected

|

No. |

Web accessibility non-compliance problem type |

Number of websites |

Percentage of websites |

|

1 |

Names and labels: Links do not have a discernible name |

12 |

100.00 |

|

2 |

Contrast: Background and foreground colors do not have a sufficient contrast ratio |

10 |

83.00 |

|

3 |

Names and labels: Image elements do not have [alt] attributes |

7 |

58.33 |

|

4 |

Navigation: Heading elements are not in a sequentially-descending order |

7 |

58.33 |

|

5 |

ARIA: ARIA input fields do not have accessible names |

3 |

25.00 |

|

6 |

ARIA: Elements with an ARIA [role] that require children to contain a specific [role] are missing some or all of those required children |

3 |

25.00 |

|

7 |

Names and labels: Buttons do not have an accessible name |

3 |

25.00 |

|

8 |

ARIA: [aria-hidden="true"] elements contain focusable descendents |

2 |

16.67 |

|

9 |

Best practices: [user-scalable="no"] is used in the <meta name="viewport"> element or the [maximum-scale] attribute is less than 5 |

2 |

16.67 |

|

10 |

Names and labels: <frame> or <iframe> elements do not have a title |

2 |

16.67 |

|

11 |

Navigation: Some elements have a [tabindex] value greater than 0 |

2 |

16.67 |

|

12 |

ARIA: [aria-*] attributes do not match their roles |

1 |

8.33 |

|

13 |

ARIA: [role] values are not valid |

1 |

8.33 |

|

14 |

Names and labels: Form elements do not have associated labels |

1 |

8.33 |

|

15 |

Navigation: [id] attributes on active, focusable elements are not unique |

1 |

8.33 |

|

16 |

Tables and lists: List items (<li>) are not contained within <ul> or <ol> parent elements |

1 |

8.33 |

|

17 |

Tables and lists: Lists do not contain only <li> elements and script supporting elements (<script> and <template>) |

1 |

8.33 |

Figure 2. Accessibility check option in MOODLE text editor

There are accessibility plugins for popular Content Management Systems (CMS) as well. They enable additional helpful features that can enhance the visual appearance of the web content with options such as resize font (increase/decrease), turn on grayscale, negative contrast, high contrast, light background, underline links, and readable font (Figure 3.).

Finally, there are web accessibility features already built in the core of the most popular CMS.

So far, only 7 out of 12 (58,33%) universities have some kind of web accessibility plug-ins or widgets or adjustments embedded in their websites home pages (such as USERWAY, One Click Accessibility, and the possibility to change background and foreground colours only). In one case, the web accessibility plug-in/widget is not visible immediately when accessing a website until the hidden menu is activated.

In the Article 7, Additional Measures, of the Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of The Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies (European parliament, 2016) it is stated that “Member States shall ensure that public sector bodies provide and regularly update a detailed, comprehensive and clear accessibility statement on the compliance of their websites and mobile applications with this Directive”. Regarding this, only 7 out of 12 (58,33%) universities have their Accessibility Statements published on their websites, giving “explanation concerning those parts of the content that are not accessible, and the reasons for that inaccessibility and, where appropriate, the accessible alternatives provided for” as defined in the EU Directive (European parliament, 2016). Additionally, from the published accessibility statements it is visible that the web accessibility and the content of those accessibility statements are not checked and changed on regular bases.

Figure 3. One Click Accessibility plugin for Wordpress

Conclusion

Web accessibility is a legal but also a moral obligation of all web content creators which must be fulfilled in order to ensure accessibility to all users. Higher education institutions / universities should be examples of best practices in the assurance of web and digital accessibility.

The analysis of the accessibility of the 12 Croatian universities’ websites home pages shows that they have issues regarding names and labels - links do not have a discernible name (all of the websites analysed, 100%), with contrast - background and foreground colors do not have a sufficient contrast ratio (most of the websites, 83.00 %), while more than a half of the websites (58.33%) have issues related to names and labels - image elements do not have [alt] attributes and navigation - heading elements are not in a sequentially-descending order. No matter the availability of web accessibility plug-ins or widgets, only 7 out of 12 (58,33%) universities have them or some kind of simple web accessibility adjustments embedded. The same number (percentage) of websites have their accessibility statement published.

The results of the analysis show and emphasise the need for the improvement of the web accessibility of university websites.

References

Acosta-Vargas, P., Acosta, T., & Lujan-Mora, S. (2018). Challenges to assess accessibility in higher education websites: A comparative study of Latin America universities. IEEE access, 6, 36500–36508.

Acosta-Vargas, P., Luján-Mora, S., & Salvador-Ullauri, L. (2016). Evaluation of the web accessibility of higher-education websites. In 2016 15th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

Agangiba, M. A., Nketiah, E. B., & Agangiba, W. A. (2017). Web accessibility for the visually impaired: A case of higher education institutions’ websites in ghana. In International Conference on Web-Based Learning (pp. 147–153). Springer, Cham.

AlMeraj, Z., Boujarwah, F., Alhuwail, D., & Qadri, R. (2021). Evaluating the accessibility of higher education institution websites in the State of Kuwait: empirical evidence. Universal Access in the Information Society, 20(1), 121–138.

ETSI, CEN & CENELEC (2021). Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services - EN 301 549 V3.2.1 (2021-03) /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://rdd.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/SDURDD-dokumenti/en_301549v030201p.pdf

European parliament (2016). Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of The Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies. Retrieved on 25th February 2022 from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L2102&from=EN

Hrvatski sabor [Croatian Parliament] (2019). Zakon o pristupačnosti mrežnih stranica i programskih rješenja za pokretne uređaje tijela javnog sektora. Narodne novine 17/19, 23. rujan 2019. /online/ [Act on the Accessibility of Websites and Software Solutions for Mobile Devices of Public Sector Bodies (Official Gazette 17/19, September 23rd, 2019)]. Retrieved on 15th December 2021. from https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2019_02_17_358.html

Hubble and Bolton, (2021). Support for disabled students in higher education in England /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8716/CBP-8716.pdf

İşeri, E. İ., Uyar, K., & İlhan, Ü. (2017). The accessibility of Cyprus Islands’ higher education institution websites. Procedia computer science, 120, 967–974.

Ismail, A., & Kuppusamy, K. S. (2019). Web accessibility investigation and identification of major issues of higher education websites with statistical measures: A case study of college websites. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences.

Ismail, A., Kuppusamy, K. S., & Paiva, S. (2020). Accessibility analysis of higher education institution websites of Portugal. Universal Access in the Information Society, 19(3), 685–700.

ISO/IEC (2012). ISO/IEC 40500:2012 Information Technology — W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0

Kamal, I. W., Alsmadi, I. M., Wahsheh, H. A., & Al-Kabi, M. N. (2016). Evaluating web accessibility metrics for Jordanian universities. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 7(7), 113–122.

Kiš-Glavaš L. (2016). Smjernice za unapređenje sustava potpore studentima s invaliditetom u visokom obrazovanju u Republici Hrvatskoj /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://mzo.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/Obrazovanje/VisokoObrazovanje/RazvojVisokogObrazovanja/Smjernice%20za%20unapre%C4%91enje%20sustava%20potpore%20studentima%20s%20invaliditetom%20u%20visokom%20obrazovanju%20u%20Republici%20Hrvatskoj.pdf

Laufer Nir, H., & Rimmerman, A. (2018). Evaluation of Web content accessibility in an Israeli institution of higher education. Universal Access in the Information Society, 17(3), 663–673.

Máñez-Carvajal, C., Cervera-Mérida, J. F., & Fernández-Piqueras, R. (2021). Web accessibility evaluation of top-ranking university Web sites in Spain, Chile and Mexico. Universal Access in the Information Society, 20(1), 179–184.

Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy & Ministry of Defence, (2021). National Strategy for Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities 2021 – 2027 of Republic of Croatia. (Draft document). /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://esavjetovanja.gov.hr/ECon/MainScreen?entityId=18803#_Toc80878268

Mozilla (2022). ARIA. /online/. Retrieved on 2nd February 2022 from https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Accessibility/ARIA

W3C (2022a). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/

W3C (2022b). W3C Accessibility Standards Overview. /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/

W3C (2022c). Introduction to Understanding WCAG - Understanding the Four Principles of Accessibility. /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG21/Understanding/intro#understanding-the-four-principles-of-accessibility

W3C (2022d). Introduction to Understanding WCAG - Understanding the Four Principles of Accessibility. /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-principles/#perceivable

Web Accessibility Initiative - WAI (2021). Introduction to Web Accessibility - What is Web Accessibility. /online/. Retrieved on 3rd February 2022 from https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro/