ICT In Primary Education – Students’ Perspective

|

Teaching (Today for) Tomorrow: Bridging the Gap between the Classroom and Reality 3rd International Scientific and Art Conference |

|

|

|

| Section - Education for digital transformation | Paper number: 1 |

Category: Original scientific paper |

Abstract |

|

In conclusion,

|

|

Key words: |

|

|

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a transformative force across industries and academic fields, influencing how societies operate and how individuals engage with technology (Russell & Norvig, 2021). As AI technologies continue to advance, understanding the factors that shape attitudes towards AI becomes increasingly important, especially among university students who represent the future workforce and societal leaders. Positive attitudes towards AI may foster greater acceptance and effective utilization of these technologies, while negative attitudes could hinder their adoption and integration (Grassini, 2023). Consequently, exploring the demographic influences on attitudes toward AI provides a pathway for tailoring AI education and policy-making to address diverse needs and perceptions. From personalized learning systems in education to intelligent medical diagnostics and autonomous transportation, AI has proven its potential to improve efficiency, decision-making, and innovation (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2017; Russell & Norvig, 2021). However, its rapid development has also sparked debates surrounding ethical concerns, including algorithmic biases, data privacy, and potential job displacement (Tegmark, 2017; Binns, 2018). As AI becomes increasingly ubiquitous, understanding the attitudes and perceptions of university students—the future leaders, workforce, and educators—toward AI is essential to facilitate its acceptance and integration.

Attitudes towards AI are not uniform and often vary based on demographic variables such as gender, age, education level, and field of study. Gender differences in technology adoption have been well-documented, with females often exhibiting either higher levels of caution or more positive attitudes towards certain technologies, including AI, compared to their male counterparts (Venkatesh et al., 2003). These differences could be attributed to social, cultural, and experiential factors influencing perceptions of technological utility and risks. Similarly, field of study significantly impacts students’ attitudes toward AI. For instance, students in social sciences or social work may approach AI with a focus on its ethical implications and potential societal benefits, while students in technical disciplines may emphasize its functionality and innovation (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). However, the role of other demographic factors, such as age and education level, in shaping attitudes remains less explored and often inconclusive (Wang et al., 2022). Conversely, students in the social sciences or humanities may be more concerned with its ethical, societal, and cultural implications (Holmes et al., 2019; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). These disciplinary differences underline the importance of tailored AI education to address varied perspectives and needs. Despite the growing body of literature, the role of other demographic factors, such as age and education level, remains less conclusive. Some studies suggest younger individuals are more open to technological innovations due to higher exposure, while others emphasize the significance of educational exposure over age (Makransky et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022).

In this study, we investigate the attitudes of university students at the University of Shkoder toward AI and explore how demographic factors influence these attitudes. Using a quantitative descriptive research design and the AI Attitude Scale (AIAS-4) developed by Grassini (2023), we examine variations in attitudes across gender, age groups, education levels, and fields of study. By addressing gaps in existing research and identifying demographic patterns, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the sociocultural dynamics of AI acceptance.

The integrationfindings offrom Informationthis research have practical implications for developing targeted AI education programs and Communicationinforming Technologyinstitutional (ICT)strategies intoto primaryenhance AI literacy. Understanding these attitudes can aid in promoting diversity and inclusivity in AI education has revolutionized the teaching and learningpolicy-making, process,ensuring aligningthat educationstudents from varied academic backgrounds are equipped to engage meaningfully with theAI demands of an increasingly digital society. ICT tools, such as interactive whiteboards, digital textbooks, gamified applications, and adaptive learning platforms, offer opportunities to make learning more engaging, interactive, and personalized. These technologies not only support cognitive development but also foster essential 21st-century skills, such as critical thinking, creativity, and digital literacy (Dingli et al. (2018)). However, the successful implementation of ICT in primary education requires addressing significant challenges, including teacher readiness, student attitudes, the digital divide, and the development of infrastructure and supportive policies.

technologies.

ICTBy toolsexamining inthe primaryexisting education are transforming traditional pedagogies by providing diverseliterature and interactiveconducting methodsempirical forresearch, deliveringwe content. Digital platforms and applications offer a range of multimedia resources, enabling studentsseek to visualizeaddress andthe interactfollowing withresearch complex concepts. For example, Saif et al. (2021) presents how augmented reality (AR) enhances student engagement and comprehension. AR allows students to manipulate virtual models or explore learning content, turning abstract topics into tangible learning experiences.

question:

AdaptiveHow educationaldo platformsgender, useage, artificialeducation intelligence (AI) to tailor content to individual student needs, addressing specific strengthslevel, and weaknesses. This customization has been shown to improve learning outcomes and foster inclusivity by supporting students with varying abilities and learning styles (Lara Nieto-Márquez et al. (2020)). In addition, gamified platforms enhance motivation and sustained interest, as students receive real-time feedback and experience a sensefield of accomplishment.

ICT also facilitates collaborative learning. Digital tools enable students to work together on projects and connect with peers across the globe. These interactions encourage teamwork, cross-cultural understanding, and problem-solving. For instance, Kangas et al. (2022) highlighted how the integration of ICT in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) projects promote creativity and interdisciplinary thinking, preparing students for the complex challenges of the future.

The success of ICT in primary education depends significantly on students' attitudes toward technology. Positive perceptions can enhance engagement, motivation, and academic achievement. Rodriguez-Jimenez et al. (2023) argue that students often view ICT as a valuable addition to their learning experiences, particularly when tools are intuitive and aligned with their interests. Interactive applications and gamification have been particularly effective in maintaining students’ curiosity and enthusiasm.

However, not all students embrace ICT seamlessly. Technical challenges, lack of relevance in digital content, and insufficient teacher support can lead to frustration and disengagement (Althubyani (2024)). Ensuring that digital tools are accessible, reliable, and well-integrated into the curriculum is essential for fostering a positive learning environment.

Teachers are pivotal to the effective implementation of ICT in primary education. Their preparedness, attitudes, and teaching strategies directly impact how technology is utilized in classrooms. Despite the growing availability of digital tools, many educators feel inadequately trained to integrate ICT into their teaching practices effectively. Althubyani (2024) emphasized the importance of professional development programs in equipping teachers with the technical skills and pedagogical frameworks needed to harness ICT effectively.

Furthermore, teacher attitudes toward ICT play a crucial role in its adoption. Educators who view technology as an enabler of innovative teaching are more likely to use it creatively and confidently. Building a culture of collaboration, where teachers share best practices and successes, can enhance their confidence and willingness to experiment with new digital tools.

While ICT has the potential to democratize education, socio-economic disparities often hinder its equitable implementation. The digital divide remains a significant barrier, with students from underprivileged backgrounds facing limited access to devices and reliable internet connectivity. Kangas et al. (2022) stressed that this inequality restricts opportunities for many students, exacerbating existing educational disparities.

Addressing the digital divide requires multi-faceted approaches, including government initiatives to provide devices and internet access to underserved communities, investment in school infrastructure, and partnerships with technology developers. Schools can also play a crucial role by implementing inclusive ICT programs and ensuring that all students, regardless of their socio-economic background, have opportunities to develop digital skills.

The successful integration of ICT in primary education calls for a coordinated approach involving educators, policymakers, and technology developers. Policies should prioritize investments in teacher training, infrastructure, and research to support sustainable ICT adoption. Furthermore, ICT initiatives must align with broader educational goals, such as fostering critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration.

Research into emerging technologies like virtual reality (VR), AI, and AR will continue tostudy shape the future of ICT in education. Saif et al. (2021) suggested that these technologies could create even more immersive and engaging learning experiences, further enriching the educational landscape. However, to maximize the potential of ICT, it is essential to address challenges related to access, equity, and teacher readiness.

This paper examines students’ attitudes toward ICT in primary education, drawing on recent studies to explore the factors influencing these attitudes and their implications for teaching and learning. By synthesizing evidence from contemporary research, it aims to provide insights into how educators can optimize ICT integration to maximize its benefits while addressing its challenges. Ultimately, understanding and shaping students' attitudes toward ICT will be crucial in preparing them for a rapidly evolving digital world.AI?

Methodology

Research Design

This study exploresadopted a descriptive research design within a quantitative research approach to explore university students’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence (AI) and the attitudesdemographic ofvariables primaryinfluencing schoolthese studentsattitudes. towardThis the use of ICT in their education. Studyapproach was conductedchosen betweento Aprilsystematically measure and Mayanalyze 2023,students’ theperspectives researchon surveyedAI, 199 students, aiming to gainproviding insights into theirvariations perspectivesacross gender, academic discipline, age, and educational level.

Participants and sampling

The study involved 170 university students from the University of Shkoder, where 144 are females (84.7%) and 26 are males (15.3%). Participants were selected through a non-probability sampling method, specifically convenience sampling, while practical for this study, has limitations in terms of generalizability. To mitigate potential biases, efforts were made to include students from diverse academic disciplines, ensuring representation from fields such as social work, psychology, and physical education.

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows:

Enrollment as a student at the University of Shkoder during the academic year 2023-2024.

Availability and willingness to participate in an online survey. Basic familiarity with digital technologies to ensure valid responses to the online questionnaire.

Instruments

The AI Attitude Scale (AIAS-4), developed by Grassini (2023), served as the primary tool for measuring students' attitudes toward AI. The AIAS-4 is a psychometrically validated instrument specifically designed to assess perceptions of AI across multiple dimensions, including its societal, ethical, and practical implications. The AIAS-4 consists of 20 items measured on howa ICT5-point impactsLikert scale, where responses range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .915. The scale evaluates attitudes along the following dimensions:

1. Social utility: perceptions of AI’s potential to address societal challenges.

2. Ethical concerns: concerns regarding the moral implications of AI usage.

3. Practical benefits: views on the efficiency and advantages AI brings to various fields.

4. Personal acceptance: willingness to engage with and trust AI technologies.

For this study, the AIAS-4 was administered online through a survey platform. The online format enabled wide accessibility and ease of participation while reducing logistical barriers. Before distribution, the survey was pilot-tested with a small group of students to ensure clarity and reliability of the instrument in the study's context.

Procedure

Participants were invited via email to complete the online survey. The survey link included a brief description of the study’s purpose, an assurance of confidentiality, and an informed consent form. Participation was voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any point without penalty. The data collection process spanned two weeks, during which reminders were sent to maximize participation. To ensure data quality, incomplete responses were excluded from the final analysis.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using statistical software. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and overall attitudes toward AI. Inferential analyses, including t-tests and ANOVA, were performed to examine differences in AI attitudes across demographic groups. The reliability of the AIAS-4 in this sample was assessed using Cronbach's alpha, ensuring the instrument’s internal consistency.

Ethical considerations

The study complied with ethical research standards. Participants were assured of their learning experience. By examining students’ experiences, preferences,anonymity and the challenges they face, this paper aims to provide a deeper understandingconfidentiality of the role ICT plays in shaping their educationalresponses. journeyNo personally identifiable information was collected, and toall offerdata recommendationswere forstored optimizing its use in primary education.securely.

Results

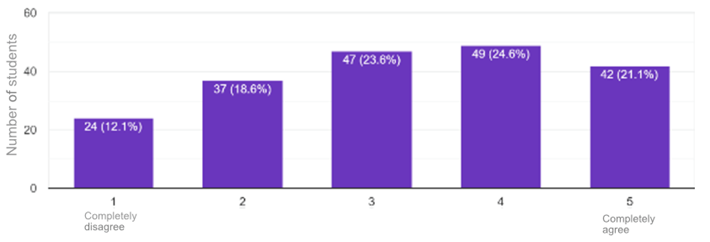

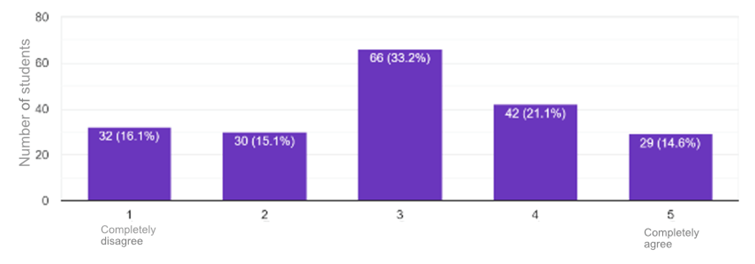

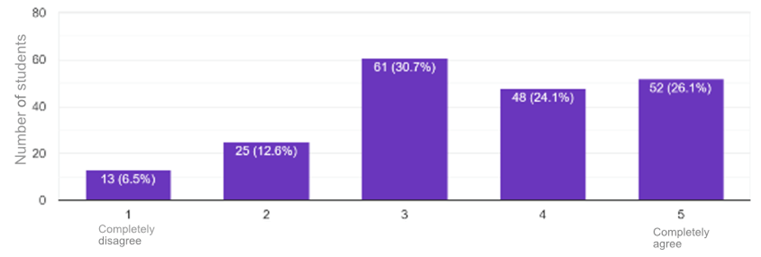

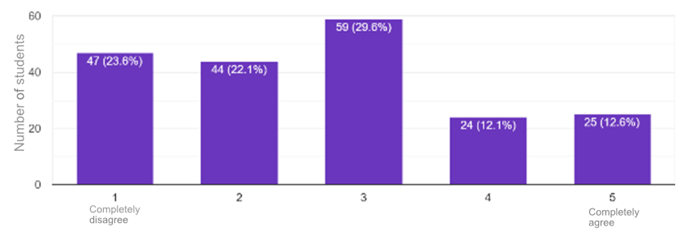

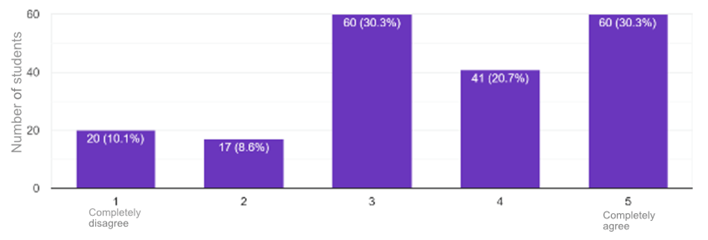

StudentsThe descriptive analysis of the survey data reveals interesting insights about the characteristics of the respondents. Among the students, 15% were male, while the majority, accounting for 85%, were female. This indicates a significant gender imbalance in the sample. The respondents’ ages were categorized into several groups, each representing a specific range. The largest age group was 20-21 years old, comprising 41.8% of the respondents. Following closely behind was the 18-19 years old group, accounting for 38.2%. The smaller age groups consisted of 22-23 years old (7.1%), 24-25 years old (4.1%), and those above 26 years old (8.8%). These results suggest that the majority of the respondents were in their late teens to early twenties, with a smaller proportion being older than 25. Among the respondents, 29.4% were studying Psychology, while 42.4% were pursuing Social Work and 28.2% were engaged in Physics education. These findings indicate that Social Work was the most prevalent discipline among the respondents. The analysis revealed that the largest proportion of respondents (51.8%) were in their second year of study. The first-year students accounted for 30% of the sample. The subsequent years had tosmaller express their agreementpercentages, with 17 statements about their attitudes about ICT10% in educationthe onthird ayear, scale2.9% fromin 1the (completelyfourth disagree)year, toand 55.3% (completelyin agree).the fifth year. These findings suggest that the survey primarily captured the perspectives of second-year students, with fewer respondents in higher academic years.

Independent samples t-test results show a significant difference in AI attitude scores between females and males. The results revealed that female students demonstrated more positive attitudes toward artificial intelligence (M = 73.16, SD = 11.49) compared to male students (M = 66.28, SD = 9.64), t(167) = 2.823, p < .05.

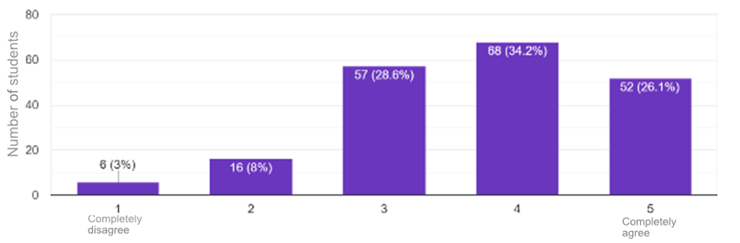

FigureTable 1. 1

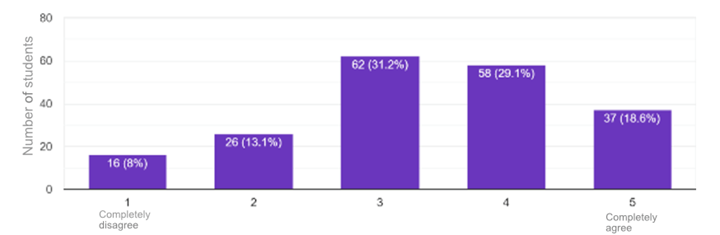

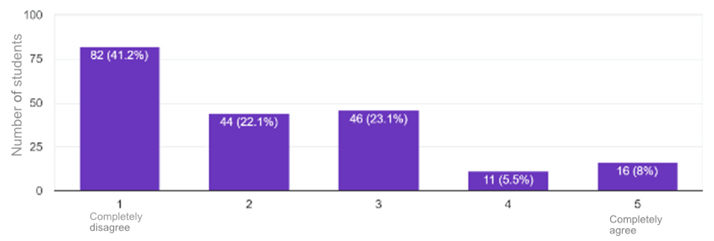

IMean thinkScores, IStandard manageDeviation, myand screent-values timeof wellfemale and male students in relation to artificial intelligence.

|

Gender |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t (167) |

F |

P |

|

|

|

|

144

|

73.16 |

11.49 |

2.823 |

0.321 |

.005* |

|

Male |

25 |

66.28 |

9.64 |

To explore potential differences in FigureAI 1attitudes reflectacross adifferent mixedage butgroups, relativelyan balancedone-way view on screen time management. While almost halfanalysis of the studentsvariance (47.7%)ANOVA) ratedwas theconducted. statementHowever, positively (Agree or Strongly Agree), ano significant numberdifferences in AI attitudes (31.2%)F(4,165) remained= neutral,1.145, andp about> 21.1%.05) expressedwere disagreementfound oracross stronglydifferent disagreed.age This suggests that, while many students feel they manage their screen time well, there is still a notable portion who may either struggle with it or are uncertain about how well they manage it.groups.

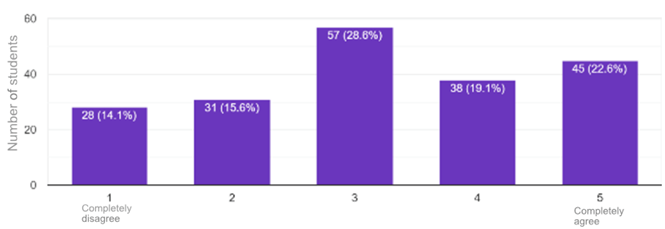

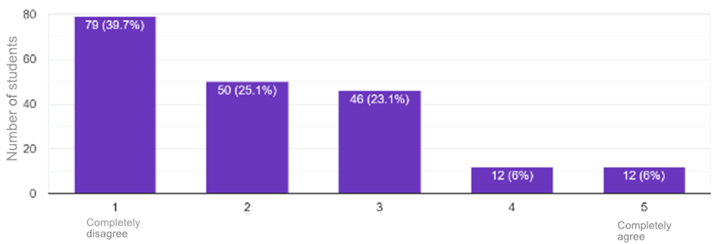

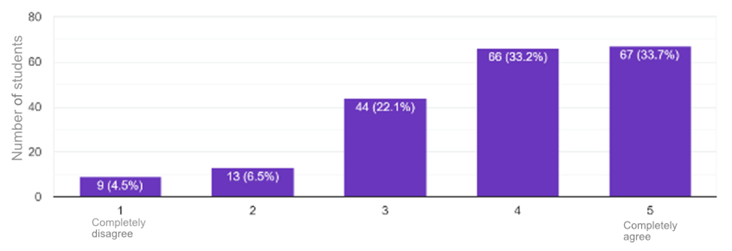

FigureTable 2.2

IMean, feelstandard greatdeviation, afterF spendingand moreP thanfor anage hourvariable in frontattitudes oftoward theartificial screenintelligence

|

Variables |

Group |

N |

Mean |

|

F (4, 165) |

P

|

|

|

18-19

|

65 12 7 15 |

71.83 72.73 72.83 63.42 73.60 |

11.70 10.75 11.76 18.98 8.71 |

|

.337 |

The results of differences in artificial intelligence across different years of study indicated that there are no significant differences in AI attitudes across different groups F(4,165) = .811, p > .05.

Table 3

Mean, standard deviation, F and P of years of study in attitudes toward artificial intelligence

|

Variables |

Group |

N |

Mean |

|

F (4, 165) |

P

|

|

AI attitudes |

First Second Third Fourth Fifth |

51 89 17 5 10 |

13.88 13.58 13.88 7.00 8.30 |

13.83 11.86 11.03 9.54 5.77 |

.811 |

.520 |

ANOVA results reveal a statistically significant difference in AI attitude scores between the three fields of study F(2,167) = 3.456, p < .05. The results indicated that students of social work exhibited more positive attitudes toward artificial intelligence (M = 73.76, SD = 11.69) compared to students of psychology (M = 73.14, SD = 9.76) and physics education (M = 68.48, SD = 12.17).

Table 4

Mean, standard deviation, F and P for academic discipline in attitudes toward artificial intelligence

|

Variables |

Group |

N |

Mean |

|

F (2, 167) |

P

|

|

AI attitudes |

Psychology Social Work Physics Education |

50 72 48 |

73.14 73.76 68.48 |

9.76 11.69 12.17 |

3.456 |

.005 |

Discussion

The findings from this study provide valuable insights into the complex relationship between university students' attitudes toward artificial intelligence (AI) and demographic factors such as gender, academic discipline, age, and educational level. One of the most striking results is the significantly more positive attitude of female students toward AI compared to their male counterparts. This finding aligns with research indicating that women often view AI technologies through a lens of social utility and practical benefits (Grassini, 2023). It reflects broader societal trends wherein women, historically underrepresented in technological fields, are increasingly recognizing the potential of AI to address societal and workplace challenges. Initiatives aimed at fostering gender diversity in AI-related disciplines could build on this trend, encouraging more women to pursue AI-focused careers and academic pursuits (Brown & Smith, 2021).

The study also highlights that Social Work students exhibit notably positive attitudes toward AI compared to students in fields such as Psychology and Physical Education. This enthusiasm could stem from the practical benefits AI offers to social work practice, including client management systems, predictive analytics for social interventions, and enhanced accessibility of services (Johnson et al., 2022). Social Work students may view AI as a tool to amplify their impact in addressing complex societal issues. This underscores the importance of designing AI curricula that resonate with the specific interests and professional goals of students within particular disciplines. Tailoring AI education to highlight relevant application such as ethical AI use in Psychology or AI-driven performance analytics in Physical Education could enhance engagement and learning outcomes across diverse fields of study.

Interestingly, the results showed no significant differences in AI attitudes among students across various age groups. This finding challenges assumptions that younger students, often labeled as “digital natives,” might have more favourable attitudes toward technology. Instead, it suggests that AI-related attitudes are influenced by factors beyond age, such as exposure to AI applications, personal interest, or perceived relevance to one’s field of study (Nguyen & Walker, 2023). Similarly, the lack of significant differences in AI attitudes across educational levels indicates that exposure to AI may be relatively consistent among undergraduate students, regardless of their academic progression. This consistency raises an important question: Are current AI education strategies adequately preparing students for the complexities of the evolving technological landscape, or do they merely provide a superficial introduction to AI concepts?

The methodological approach used in this study provides a strong foundation for understanding student attitudes but is not without its limitations. The use of convenience sampling, while pragmatic, limits the generalizability of the findings to broader student populations. Moreover, the online administration of the AI Attitude Scale (AIAS-4) might have introduced a selection bias, favouring participants who are more comfortable engaging with technology. Future research should consider employing more diverse sampling techniques and combining quantitative surveys with qualitative methods, such as interviews or focus groups, to capture a richer understanding of student perspectives (Smith et al., 2020).

These findings have significant implications for higher education institutions. The variation in attitudes across academic disciplines highlights the necessity of moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches to AI education. For instance, Social Work students might benefit from courses emphasizing AI's role in advancing social justice, while Psychology students could explore ethical considerations and cognitive models in AI development. Moreover, the enthusiasm of female students toward AI represents an opportunity to create inclusive and supportive learning environments that encourage their sustained engagement and leadership in AI-related fields (Garcia et al., 2021).

Interdisciplinary learning opportunities could further enrich students’ understanding of AI. Collaborative projects involving students from diverse academic backgrounds may foster a broader appreciation of AI's multifaceted applications while addressing potential gaps in knowledge or perspective. Additionally, longitudinal studies tracking changes in student attitudes over time could provide valuable insights into how exposure to AI in academic and professional contexts shapes perceptions and readiness to engage with AI technologies.

Finally, this study highlights the importance of continuous research into AI attitudes to ensure that educational practices remain aligned with the evolving needs and expectations of students. As AI continues to permeate every aspect of society, understanding and addressing the factors that influence student attitudes will be critical to preparing the next generation for the opportunities and challenges of an AI-driven world.

Conclusion

This study underscores the significant role of gender and academic discipline in shaping university students' attitudes toward AI, while finding no significant impact of age or educational level. Female students and Social Work majors demonstrate notably positive attitudes toward AI, likely influenced by their perception of AI’s societal relevance and practical applications. The findings highlight the importance of creating tailored and inclusive educational approaches to AI, emphasizing the need for ongoing research to understand the dynamic interplay between demographic factors and AI attitudes.

Recommendations

Develop AI courses that address the unique needs and challenges of individual disciplines. For example, focus on AI’s potential in social justice for Social Work students or its ethical implications for Psychology students.

Design programs and workshops that actively encourage female students to engage with AI, emphasizing its relevance to societal and professional contexts.

Facilitate opportunities for students from diverse fields to collaborate on AI-related projects, promoting a holistic understanding of AI applications.

Conduct longitudinal and mixed-method studies with diverse samples to validate findings and explore additional demographic and contextual variables influencing AI attitudes.

Integrate AI education into core curricula across age groups and educational levels to ensure consistent exposure and engagement with AI concepts.

Identify and mitigate factors that may deter certain groups from engaging with AI, ensuring equitable access and opportunities for all students.

Acknowledgment

We express our gratitude to the University of Shkoder “Luigj Gurakuqi” for providing financial support for our participation in this scientific conference.

References

Althubyani, A. R. (2024). Digital Competence of Teachers and the Factors Affecting Their Competence Level: A Nationwide Mixed-Methods Study. Sustainability, 16(7), 2796.

Dingli,Binns, S., Baldacchino, L.A. (2018). CreativityAlgorithmic andbias digitalin literacy:AI skillssystems. for the future.Springer.

Rodriguez-Jimenez,Brown, C., de la Cruz-Campos, J. C., Campos-Soto, M. N.A., & Ramos-Navas-Parejo,Smith, K. (2021). Gender diversity in artificial intelligence: Fostering inclusivity in AI-focused careers. Technology and Society, 33(1), 56-68.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2017). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

Garcia, E., Thompson, J., & Taylor, M. (2021). Inclusive learning environments in AI education: Engaging female students in technology. Journal of Educational Technology, 45(2), 102-115.

Grassini, S. (2023). TeachingDevelopment and learning mathematics in primary education: The role of ICT-A systematic reviewvalidation of the literature.AI MathematicsAttitude Scale (AIAS-4): A brief measure of attitude toward Artificial Intelligence,. 11(2), 272.DOI:10.31234/osf.io/f8hvy.

Kangas,Holmes, K.B., Sormunen,S. K.D. Binns, & D. G. Washington. (2019). The ethical implications of artificial intelligence: A sociocultural perspective. Technology and Ethics, 15(2), 55-73.

Johnson, M., Williams, L., & Korhonen,Harris, T. (2022). Creative learning with technologiesAI in youngsocial students’work STEAMpractice: education.Transforming Inclient STEM, Robotics, Mobile Apps in Early Childhoodmanagement and Primaryintervention Education: Technology to Promote Teaching and Learning strategies(pp. 157-179). Singapore:Journal Springerof NatureSocial Singapore.Work Technology, 27(3), 123-135.

LaraMakransky, Nieto-Marquez, N.G., Baldominos,M. A.,M. CardenaBørne, Martinez,L. A.,T. Jensen, & PerezD. Nieto,E. M. A.Damsgaard. (2020). AnThe exploratory analysisrole of theeducation implementationin shaping attitudes toward technology. Journal of Technology and useEducation, of an intelligent platform for learning in primary education. Applied Sciences, 10(8(3), 983.121-135.

Saif,Nguyen, A.T., & Walker, R. (2023). Age and attitude: Exploring generational differences in AI adoption. Technology and Education Review, 29(4), 204-215.

Russell, S., Mahayuddin, Z. R., & Shapi'i,Norvig, A.P. (2021). AugmentedArtificial realityintelligence: basedA adaptivemodern andapproach collaborative(4th learninged.). Pearson.

Smith, D., O’Reilly, K., & Collins, B. (2020). Advancing AI research through mixed-methods forapproaches: improvedIntegrating primaryqualitative educationperspectives towardsinto fourthquantitative industrial revolution (IR 4.0)studies. International Journal of AdvancedAI ComputerResearch ScienceMethods, 12(1), 58-73.

Tegmark, M. (2017). Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. Alfred A. Knopf.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Wang, J., Chen, X., & Zhang, J. (2022). Exploring the influence of education on technology adoption: A meta-analysis. Technology, Learning, and Applications,Innovation, 12(6).21(4), 175-188.

Zawacki-Richter, O., B. H. K. S. Hans, & C. D. J. L. M. (2019). AI in higher education: Trends, benefits, and ethical considerations. Journal of Higher Education Research, 47(4), 44-59.