The Digital Literacy of First Grade Primary School Students

|

Teaching (Today for) Tomorrow: Bridging the Gap between the Classroom and Reality 3rd International Scientific and Art Conference |

|

|

|

| Section - Education for |

Paper number: |

Category: Original scientific paper |

Abstract |

|

|

|

Key words: |

Introduction

Self-compassionChildren reflectsbegin beingto kinduse digital technologies at a very early age: two-year-old toddlers regularly watch films and understandingvideos towardand oneselflisten amidto lifemusic difficultieson tablet computers (Neff,Ólafsson 2003a)et al, 2014). ThroughChildren's self-compassionInternet oneuse canis restraingenerally fromover self-criticism,85% over-identificationfor the age group beginning at six, rising to around 95% for older children (14 and older). One study finds that even 40% of 3 to 6-year-olds use the Internet at least once a week, predominantly with the experienced difficulties and isolating from others. Self-compassion is usually operationalized as a multidimensionaltablet construct that entails self-kindness, mindful awareness of painful experiences and recognizing that difficulties are part of the shared human experiencedevice (Neff, 2003a). Studies have confirmed that self-compassion relates to higher subjective and psychological well-being (e.g., Neff, 2003b; TranÓlafsson et al.,al, 2022)2014).

Today's psychologychildren inuse educationdigital recognised self-compassion as a positive correlate of students’ stress resilience (Egan et al., 2021; McArthur et al., 2017), adaptive coping (Ewert et al., 2021; Neff, 2005) and various indicators of well-being (Fong & Loi, 2016; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Rahe et al., 2022). Thus, it seems important to study factors that promote self-compassion, especially among students who are preparing for stressful and demanding professionsdevices, such as preschooltablets, teaching.smartphones and computers, from an early age. Radesky et al. (2020) report research results on the sample of 346 parents and guardians of children aged 3 to 5 years where children were using tablets and smartphones to access applications such as YouTube, YouTube Kids, Internet browser, Quick Search Box or Siri, and streaming video services. 121 children (35%) had their own devices, and their average daily usage was 115 minutes (SD 115.1; range 0.20–632.5).

PreviousIt studiesis linkedimportant self-compassionto prepare children and young people to use information and communication technology safely and responsibly. In the era when Artificial Intelligence (AI) is having a growing influence on people’s everyday lives, it is important to acquire knowledge and skills to learn and work with mindfulnessthe (Egannewest etdigital al., 2021; Neff, 2003a; Tran et al., 2022). Mindfulness reflects a particular way of focusing attentiontechnologies and awareness on a present moment with a non-judgmental and non-reactive attitude towards ongoing experiences (Baer et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003). Although mindfulness is often studied as a momentary state that can be reached through meditative practice it can also be studied as a multifaceted disposition, i.e., a general tendency to be moreprepared mindfulfor the future. This set of knowledge and skills is known as digital literacy.

“Digital literacy is the set of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that enable children to confidently and autonomously play, learn, socialize, prepare for work and participate in everydaycivic lifeaction in digital environments. Children should be able to use and understand technology, to search for and manage information, communicate, collaborate, create and share content, build knowledge and solve problems safely, critically and ethically, in a way that is appropriate for their age, local language and local culture” (BrownNascimbeni & Ryan,Vosloo 2003)(UNICEF), (2019), p. 32). Being

In aware,the non-judgementalEuropean Union, digital literacy is defined through digital competence. “Digital competence involves the confident, critical and non-reactiveresponsible touse all,of, and engagement with, digital technologies for learning, at work, and for participation in society. It includes information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation (including painfulprogramming), present-moment experiences, allows one not to get overwhelmed by or avoidant of them. This implies mindfulness as a necessary precursor of self-compassionsafety (Biehlerincluding &digital Naragon-Gainey,well-being 2022;and Neff, 2003a). Previous studies found that self-compassion was positivelycompetences related to either all facets of mindfulness (Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011) or some of the facets of mindfulness (McArthur et al.cybersecurity), 2017),intellectual with total mindfulness being consistently positively associated with self-compassion (Egan et al., 2021; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Martinez-Rubio et al., 2023; Tran et al., 2022).

Previous studies alsoproperty related self-compassionquestions, withproblem emotional intelligence (EI) (Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2011; Neff, 2003b; Şenyuva et al., 2013). EI is a part of social intelligencesolving and referscritical to positive emotional resources and adaptive emotional functioningthinking” (SchutteEuropean &Union, Loi,2019, 2014).p. EI can be conceptualized twofold, as a trait (e.g., Petride & Furnham, 2000; Wong & Law, 2002), or as an ability (Mayer et al., 2004). There are several dimensions of trait EI, but the most common operationalization includes dimensions of perceiving and understanding emotions in self (SEA), perceiving and understanding emotions in others (OEA), regulation of emotion (ROE) and use of emotion for self-motivation (UOE) (Wong & Law, 2002). Previous studies found that individuals with higher levels of EI have greater mental health (Martins et al., 2010), better relationships with others (Lopes et al. 2004), as well as higher well-being (e.g., Schutte & Malouff, 2011) and flourishing both in general population (Du Plessis, 2023) and student population (Pradhan & Jandu, 2023; Zewude et al., 2024)10).

Self-compassionDigital maycompetence alsois be related to EI since self-compassion entails recognizing and transforming painful experiences into self-kindness and self-understanding (Neff, 2003a). Overall trait EI was found to be consistently positively related to self-compassion (DiFabio & Saklofske, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2024), while the studiesone of the relationshipkey betweencompetences specificfor EIlifelong dimensionslearning (European Union, 2019, p. 5): Literacy competence, Multilingual competence, Mathematical competence and self-compassioncompetence arein somewhatscience, scarce.technology Toand ourengineering, knowledge,Digital onlycompetence, Personal, social and learning to learn competence, Citizenship competence, Entrepreneurship competence, Cultural awareness and expression competence.

More than one suchin studyfive wasyoung conductedpeople fail to reach a basic level of digital skills across the European Union (European Commission, 2020b). Providing schooling in computing equips young people with a solid comprehension of the digital realm. Initiating students into computing early on and foundemploying thatinventive specificand dimensionsengaging teaching methods across both formal and informal settings, aids in building problem-solving, creativity, and teamwork skills. Furthermore, it nurtures enthusiasm for STEM fields and potential careers, simultaneously addressing gender stereotypes. Endeavours to enhance computing education's quality and inclusivity can significantly influence the enrolment of EI,female i.e.,students self-managementin IT-related higher education programs and self-motivation,subsequently weretheir positivelyparticipation associatedin withdigital allprofessions componentsacross ofvarious self-compassioneconomic sectors (ŞenyuvaEuropean etCommission, al., 2011)2020a).

BasedThe onDigital Education Action Plan (2021-2027) has two strategic priorities (European Commission, 2020b):

- to foster a high-performing digital education ecosystem, and

- to enhance digital skills and competences for the abovedigital presented,age.

The seemslatter thatincludes therethe following activities:

- support the provision of basic digital skills and competences from an early age:

- digital literacy, including management of information overload and recognising disinformation

- computing (informatics or computer science) education

- good knowledge and understanding of data-intensive technologies, such as AI

- boost advanced digital skills: enhancing the number of digital specialists and girls and women in digital studies and careers.

One of the Action Plan activities is to encourage female participation in STEM. Female students generally perform better than male students in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) international skills tests. However, only one in three STEM graduates is a lackwoman (European Commission, 2020a).

Digital literacy and communication include knowing the possibilities of studieshardware and software solutions and developing cooperation and communication skills in an online environment. Knowledge of the possibilities of current technology and computer programs is a prerequisite for their proper selection and effective and innovative application in various fields. It is necessary to develop digital literacy from an early age and throughout schooling so that examinestudents are prepared for life and work in a digital society (Ministry of Science and Education, 2018).

According to the rolesame source, after the first year of specificstudying EIthe dimensionssubject in self-compassion as well as their mediating roleInformatics in the relationshipfield betweenof mindfulnessDigital Literacy and self-compassion.Communication, Mindfulnessthe wasstudents foundshould acquire the following learning outcomes:

- C.1.1 with the support of the teacher student uses the proposed programs and digital educational content and

- C.1.2 with the support of the teacher student creates simple digital content with very simple actions.

Digital literacy is essential to belearn, relatedwork and succeed in today’s digital society and it is important to EIprepare both on overall (Baer et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003)children and atyoung thepeople specificto EIuse dimensions level (Cheng et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2015; Park & Dhandra, 2017). Even more, mindfulness was suggested as a factor that may encourage accurate perception of emotions, development of emotional regulation,information and morecommunication adaptivetechnology emotional functioning (Park & Dhandra, 2017). In other words, mindfulness may lead to higher EI,safely and higherresponsibly EIfrom mayan leadearly to positive outcomes, such as higher self-esteem (Park & Dhandra, 2017). Based on this, it may also be posed that higher mindfulness would lead to higher EI, which would lead to higher self-compassion. However, the mediating role of EI in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion was not investigated.age.

ObjectivesMethodology

Aims

The firstresearch aimaims to explore the digital literacy of thisfirst studygrade wasprimary toschool examinestudents theand rolepossible differences by gender and by place of mindfulnessresidence and(urban EIor dimensionsrural).

self-compassion.

Hypotheses

H1: aimThere wasis tono examinestatistically thesignificant mediating role of EI dimensionsdifference in the relationshipself-assessed betweendigital mindfulnessliteracy of first grade primary school students by gender.

It is expected that the respondents will self-assess their digital literacy equally regardless of their gender (female and self-compassion.male). Female students generally perform better than male students in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) international skills tests. However, only one in three STEM graduates is a woman (European Commission, 2020). The hypothesesresearch results can show whether there are differences in the digital literacy of female and researchmale questionsstudents werealready at this early age.

H2: There is no statistically significant difference in the self-assessed digital literacy of first grade primary school students by their place of residence.

It is expected that the respondents will self-assess their digital literacy equally regardless of their place of residence (rural and urban). There is a possibility that the availability of optional subjects of informatics in urban and rural schools is not the same and that Internet connectivity in schools and at home is not the same in rural and urban areas. These two factors, the availability of optional subjects of informatics and Internet connectivity, can influence the students’ digital literacy.

H3: More than 80% of students use the Internet.

From an early age, children are exposed to the Internet through information and communication technology such as follows:smartphones, tablets, laptops and desktop computers and know how to use it to search the Internet. It is expected that more than 80% of students use the Internet.

Sample

The research sample consists of 104 first grade primary school students from four primary schools and two primary district schools (district school in Croatian: područna škola) from northwestern Croatia in the spring of 2023. There are 48 female (46.2%) and 56 male (53.8%) students in the sample. There are 53 students (51.0%) from urban places of residence and 51 students (49.0%) from rural places of residence. There are 98 students (94.2%) who attend the optional subject of informatics in the first grade, and 6 students do not attend (5.8%) (Table 1).

H1: Mindfulness is bivariately (1a) and uniquely (1b) associated with self-compassion.

H2: Overall emotional intelligence is positively associated with self-compassion.

H3: Mindfulness is bivariately associated with EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, OEA, ROE, UOE.

H4: EI is the mediator between mindfulness and self-compassion: Higher mindfulness leads to higher EI, which in turn leads to higher self-compassion.

RQ1: Which EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, OEA, ROE, UOE are bivariately (1a) and uniquely (1b) associated with self-compassion?

RQ2: Which EI dimensions, i.e., SEA (2a), OEA (2b), ROE (2c), UOE (2d) act as parallel mediators in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion?

Method

Participants and procedure

161 female students of the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb, studying early and preschool education, participated in the research (M = 25.79 years; SD = 6.42) by voluntarily and anonymously filling out the paper-pencil questionnaire during the regular academic semester.

Measures

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS, Brown & Ryan, 2003) was used to measure disposition to mindful attention and awareness. MAAS consists of 15 items (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”, reversed) which participants rated using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). The total score was calculated as a mean of all item ratings with higher results indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The scale was previously used in a Croatian sample and demonstrated good psychometric characteristics (Kalebić Jakupčević, 2014).

The Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS, Wong & Law, 2002) was used to measure four EI dimensions, i.e., self-emotion appraisal (SEA, e.g., I really understand what I feel), others’ emotion appraisal (OEA, e.g., I have good understanding of the emotions of people around me), use of emotions (UOE, e.g., I am a self-motivated person), regulation of emotion (ROE, e.g., I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties rationally). All 16 items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total average score for each WLEIS subscale was used as an independent indicator of each EI dimension. A higher result on each WLEIS subscale indicates a higher level of that EI dimensions.

The Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form (SCS–SF, Raes et al., 2011) was used to measure six components of self-compassion, i.e., over-identification (e.g., When I fail at something important to me I become consumed by feelings of inadequacy, reversed), self-kindness (e.g., I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like), mindfulness (e.g., When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation), isolation (e.g., When I’m feeling down, I tend to feel like most other people are probably happier than I am, reversed), common humanity (e.g., I try to see my failings as part of the human condition) and self-judgement (e.g., I’m disapproving and judgmental about my

own flaws and inadequacies, reversed). All 12 SCS-SF items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). A total self-compassion score was calculated as a mean of all subscale scores but omitting mindfulness subscale items, in order to avoid an artificial increase of correlation between the constructs of mindfulness and self-compassion, which is a common practice in such cases (e.g., Martínez-Rubio et al., 2023). A higher total result indicates a higher level of self-compassion.

Results

Descriptive statistics, correlations among the study variables, and Cronbach’s alpha

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations and Cronbach’s alphas are detailed in Table 1. The mean results showed that students reported moderate levels of mindfulness, both overall EI and specific EI dimensions as well as moderate levels of self-compassion. Mindfulness was positively bivariately correlated with self-compassion thus supporting Hypothesis 1a. Overall EI was bivariately positively associated with self-compassion, in line with Hypothesis 2. Mindfulness was also positively bivariately correlated with three of four EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, ROE and UOE, thus partially supporting Hypothesis 3. Regarding Research question 1a, all EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, ROE and UOE except OEA were positively bivariately correlated to self-compassion.

Table 1

Means,Respondents’ standarddemographic deviations and corelations between study variables. data

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***Self-compassion scale with mindfulness items (item 3, item 7) omitted.

Regression analysis

A linear regression analysis was performed with mindfulness and four EI dimensions as predictors and self-compassion as criteria (Table 2). Together predictors explained 42% of the variance in students’ self-compassion (F5,155 = 22.69, p < 0.001). In line with Hypothesis 1b, mindfulness was a uniquely significant predictor of self-compassion. Regarding Research Question 1b, only EI dimensions of SEA, ROE and UOE were shown as uniquely significant predictors of self-compassion. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value for EI dimensions and self-compassion ranged from 1.13 to 1.64 indicating that all values are smaller than 10, meaning that there is no multicollinearity in the independent predictors.

Table 2

Regression analysis results with self-compassion as a criteria.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. β = standardized beta coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01.

Mediation analysis

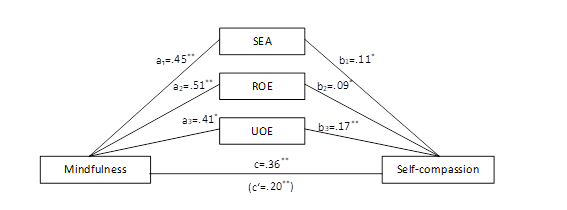

The results of the mediation analyses with EI dimensions of SEA, ROE and UOE, as parallel mediators between mindfulness and self-compassion are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 1. In line with Hypothesis 4, dimensions of EI mediated the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. In regard to Research Question 2, mediation analysis showed a partial mediation of mindfulness on self-compassion through the three EI dimensions, i.e., SEA (2a), ROE (2c) and UOE (2d) that acted as parallel mediators. The direct relation between mindfulness and self-compassion remained significant indicating the mediation was partial. Higher mindfulness fosters students’ self-compassion both directly, and indirectly via higher SEA, ROE and UOE. All mediators had a significant indirect effect on self-compassion. Although, UOE had the highest ratio of indirect to total effect (.19), specific indirect effect contrast analysis showed that the indirect effect of specific EI dimensions does not significantly differ from each other as shown in bootstrap method (with 5,000 bootstrap samples) at 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1

Mediating role of the three EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion

Note. SEA = self-emotional appraisal, ROE = regulation of emotion, UOE = use of emotion; non-standardized coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01. a relationship between predictor and mediator, b relationship between mediator and criteria, c total effect, c’ direct effect.

Table 3

Regression coefficients, standard errors, and confidence intervals for the indirect effects (mediators EI dimension: SEA, ROE, UOE)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

48 |

46.2 |

|

|

|

Male |

56 |

53.8 |

|

|

|

Total |

104 |

100.0 |

|

|

Place of residence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rural |

51 |

49.0 |

|

|

|

Urban |

53 |

51.0 |

|

|

|

Total |

104 |

100.0 |

|

|

Attending the optional subject of Informatics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

98 |

94.2 |

|

|

|

No |

6 |

5.8 |

|

|

|

Total |

104 |

100.0 |

Instruments

Since the respondents were aged six and seven, the data gathering method used was a simple questionnaire containing eleven items written on paper (Table 2).

Table 2

Questionnaire items with answer options

|

No. |

Item |

Item type |

Answer options |

|

1 |

Respondent’s gender |

Multiple choice |

Female / Male |

|

2 |

Respondent’s place of residence |

Multiple choice |

Rural / Urban |

|

3 |

I attend the optional subject of informatics in the first grade |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

4 |

I have a computer at home (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

5 |

I always ask parents or guardians for permission to use a computer (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

6 |

I know how to turn on/off the computer (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

7 |

I know the names of the computer parts (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

8 |

I know how to write a text using a computer (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

9 |

I know how to make a drawing using a computer (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

10 |

I know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube) (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

|

11 |

I understand and apply rules of conduct on the Internet (yes/no) |

Statement - multiple choice |

Yes / No |

The first two items dealt with students’ gender and the place of residence. The other nine items were statements concerning attending the optional subject of informatics, having the computer at home, asking parents or guardians for permission to use computers, knowledge of recognizing the computer parts, knowledge of the use of computer hardware and software to perform simple tasks such as turning on or off computers, writing and editing texts, make drawings, searching the Internet, and understanding and applying rules of conduct on the Internet. The students could answer if they agree or disagree with the statement with simple dichotomous options: yes or no.

The statements were chosen according to the curriculum of the optional subject Informatics and its learning outcomes in the first grade of primary school in Croatia (Ministry of Science and Education, 2018). The items of the questionnaire were adapted to the target group.

Procedure

The survey was implemented using the guidelines of the Ethical Code of Research with Children (National Ethics Committee for Research with Children, 2020).

The survey took place in two counties of northwestern Croatia from March to May 2023. The respondents were students of four primary schools, of which two are in urban and the other two in rural areas. The first author of this paper provided assistance and explanations to the respondents when they were filling out the questionnaire.

The chi-squared test is used to explore the statistically significant differences between students according to their gender and their place of residence (urban and rural).

The statistical software GNU PSPP 1.4.1 was used in the data processing.

Results

Table 3 shows the statements and the number of respondents’ responses (whether they agree with a specific statement or not). There is a total number of responses and there are responses by gender. In the next columns are the results of chi-squared tests (χ2, df, p).

Table 3.

Number of students’ responses by item and gender

|

|

Total |

Male |

Female |

|

|||||||||

|

No. |

Item |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

χ2 |

df |

p |

|||

|

1 |

I attend the optional subject of informatics in the first grade |

98 |

6 |

54 |

2 |

44 |

4 |

0. |

1 |

0. |

|||

|

2 |

I have a computer at home |

91 |

13 |

51 |

5 |

40 |

8 |

0.80 |

1 |

0.372 |

|||

|

3 |

I always ask parents or guardians for permission to use a computer |

73 |

31 |

34 |

22 |

39 |

9 |

4.27 |

1 |

0.039 |

|||

|

4 |

I know how to turn on/off the computer |

92 |

12 |

50 |

6 |

42 |

6 |

0.00 |

|

1.000 |

|||

|

|

I know the names of |

93 |

11 |

46 |

10 |

47 |

1 |

5.23 |

1 |

0. |

|

|

|

|

|

I know how to write a text using a computer |

91 |

13 |

48 |

8 |

43 |

5 |

0. |

1 |

0. |

|||

|

7 |

I know how to make a drawing using a computer |

98 |

6 |

51 |

5 |

47 |

1 |

1.15 |

1 |

0. |

|||

|

8 |

I know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube) |

98 |

6 |

52 |

4 |

46 |

2 |

0. |

1 |

0.820 |

|||

|

9 |

I understand and apply rules of conduct on the Internet |

95 |

9 |

51 |

5 |

44 |

4 |

0.00 |

1 |

1.000 |

|||

Note. B

Most of the respondents (98 out of 104, 94.2%) attend the optional subject of informatics in the first grade and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= non-standardized0.38, betadf=1, coefficients;p=0.538).

Most of the respondents (91 out of 104, 87.5%) have a computer at home and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ*2p= <0.80, df=1, p=0.372).05;

Most of the respondents (73 out of 104, 70.2%) always ask parents or guardians for permission to use a computer and there is a statistically significant difference by gender (χ**2= 4.27, df=1, p=0.039). There are more female respondents (81.3%) than male respondents (60.7%) who ask their parents or guardians for permission to use the computer.

Most of the respondents (92 out of 104, 88.5%) know how to turn on and off computers and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 0.00, df=1, p=1.000).

Most of the respondents (93 out of 104, 89.4%) know the names of the computer parts and there is a statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 5.23, df=1, p=0.022). There are more female respondents (97.9%) than male respondents (81.1%) who know the names of computer parts.

Most of the respondents (91 out of 104, 87,5%) know how to write a text using a computer and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 0.09, df=1, p=0.766).

Most of the respondents (98 out of 104, 94.2%) know how to make a drawing using a computer and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 1.15, df=1, p=0.284).

Most of the respondents (98 out of 104, 94.2%) know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube) and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 0.05, df=1, p=0.820).

Most of the respondents (95 out of 104, 91.3%) understand and apply the rules of conduct on the Internet and there is no statistically significant difference by gender (χ2= 0.00, df=1, p=1.000).

Table 4 shows the statements and the number of respondents’ responses (if they agree with a specific statement or not) by the place of residence. In the next columns are the results of chi-squared tests (χ2, df, p).

Table 4.

Number of students’ responses by item and the place of residence

|

|

Rural |

Urban |

|

|||||

|

No. |

Item |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

χ2 |

df |

p |

|

1 |

I attend the optional subject of informatics in the first grade |

50 |

1 |

48 |

5 |

1.47 |

1 |

0.225 |

|

2 |

I have a computer at home |

45 |

6 |

46 |

7 |

0.00 |

1 |

1.000 |

|

3 |

I always ask parents or guardians for permission to use a computer |

36 |

15 |

37 |

16 |

0.00 |

1 |

1.000 |

|

4 |

I know how to turn on/off the computer |

44 |

7 |

48 |

5 |

0.14 |

1 |

0.706 |

|

5 |

I know the names of the computer parts |

45 |

6 |

48 |

5 |

0.00 |

1 |

0.946 |

|

6 |

I know how to write a text using a computer |

42 |

9 |

49 |

4 |

1.59 |

1 |

0.208 |

|

7 |

I know how to make a drawing using a computer |

49 |

2 |

49 |

4 |

0.14 |

1 |

0.710 |

|

8 |

I know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube) |

45 |

6 |

53 |

0 |

4.63 |

1 |

0.031 |

|

9 |

I understand and apply rules of conduct on the Internet |

44 |

7 |

51 |

2 |

2.12 |

1 |

0.145 |

When the place of residence is considered then there is no statistically significant difference between rural and urban respondents except in the item “I know how to search the Internet” where there is a statistically significant difference (χ2= 4.63, df=1, p=0.031).01; CIThere 95%are confidencemore interval:urban LCI/UCIrespondents lower/upper(100.0%) confidencethan interval.rural respondents (88.2%) who know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube).

The research results show that most of the respondents (over 87.5%) self-assess themselves as having acquired the required learning outcomes specified in the informatics curriculum for the first grade in the field of Digital Literacy and Communication: 88.5% know how to turn on/off computers, 89.4% know the names of the computer parts, 87.5% know how to write a text using a computer, 94.2% know how to make a drawing using a computer, 94.2% know how to use the Internet, and 91.3% understand and apply the rules of conduct on the Internet. 87.5% have computers at home and 92.3% of the respondents attended the optional subject of informatics.

Discussion

This study contributes to an understandingConfirmation of the relationshiphypotheses

H1 mindfulness,states dimensionsthat there is no statistically significant difference in the self-assessed digital literacy of emotionalfirst intelligencegrade primary school students by gender (female and self-compassion.male).

AsThere expected,is no statistically significant difference in the resultsfollowing showeditems that mindfulness was positively relatedcontribute to self-compassion,the bothdigital bivariatelyliteracy of first grade primary school students:

- I know how to turn on/off the computer

- I know how to write a text using a computer

- I know how to make a drawing using a computer

- I know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube)

- I understand and uniquely.apply Theserules resultsof conduct on the Internet.

A statistically significant difference is observed only in the item “I know the names of the computer parts” where there are inmore linefemale with previous researchrespondents (Egan97.9%) etthan al.,male 2021; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; McArthur at al., 2017; Martinez-Rubio et al., 2023; Tran et al., 2022). Also as expected, results showed that overall EI was positively and moderately related to self-compassion, in line with previous studiesrespondents (Di81.1%) Fabiowho &know Saklofske,the 2021;names Heffernanof etcomputer al.,parts 2011;(χ2= Neff,5.23, 2003b;df=1, Thomas et al., 2024)p=0.022).

ThisThe studyhypothesis alsoH1 revealedis confirmed.

H2 states that there is no significant difference in the relationshipself-assessed betweendigital specificliteracy EIof dimensionsfirst grade primary school students by their place of residence (rural and self-compassion.urban Moreareas).

There resultsis showedno statistically significant difference in the following items that threecontribute to the digital literacy of fourprimary EIschool dimensions,first-grade i.e.,students:

- I know how to turn on/off the computer

- I know the names of the computer parts

- I know how to write a text using a computer

- I know how to make a drawing using a computer

- I understand and understandingapply rules of emotionconduct on the Internet.

A statistically significant difference is observed only in self,the item “I know how to search the Internet (Google, YouTube)” where there are more urban respondents (100.0%) than rural respondents (88.2%) who know how to search the Internet (χ2= 4.63, df=1, p=0.031).

The hypothesis H2 is confirmed.

H3 states that more than 80% of students use the Internet.

98 out of emotion104 (94.2%) respondents self-assess themselves as they know how to search the Internet. The hypothesis H3 is confirmed.

The research in this paper uses respondents’ self-assessed data related to their digital competence. The respondents’ age is six or seven so there is a possibility that they do not understand the questionnaire statements and/or cannot self-assess their knowledge. However, they could get guidance and help from a researcher who was present when they filled out the questionnaire. The questionnaire items were very simple and dichotomous.

It is difficult to get valid overviews of skills through questionnaires. The main reason for self-motivatingthis purposeis andthat self-regulationrespondents weretend bivariatelyto andoverestimate uniquelythemselves, associatedespecially when it comes to technical skills (Ala-Mutka, 2011).

García-Vandewalle et al. (2021) warn that evaluating subjectivity may have limitations. The respondents’ subjectivity regarding their level of knowledge is one of the main issues with self-compassion.assessment. TheseHowever, EIself-assessment dimensionsis essentiallystill representa waysvalid tool for ascertaining how students perceive their learning and enables the detection of their strengths and weaknesses.

Godaert et al. (2022) analysed 14 studies concerning the assessment of students’ digital competences in whichprimary school. The studies used various scoring systems: three were dichotomous (1=correct; 0=incorrect), four were 5-point Likert scale, one was a person7-point Likert scale, one scoring rubric (0-2 point, 0-5 points), four combined, and one not mentioned. At least five of them were using self-reported data collection. The age of the target population in the studies was mostly in the range of 9 to 13. Only one study, Jun et al (2014), included the first grade of primary school respondents of age 6.

Merritt et al. (2005) report that there were differences in respondents’ self-reported and actual digital literacy. They asked 55 students to self-report their computer literacy and later they were tested in their digital literacy. Research results show that there is ablea statistically significant difference between self-reported (N=55, M=2.164, SD=0.788) and actual tested (N=55, M=1.873, SD=0.610) levels of digital literacy.

Porat et al. (2018) report on digital literacy research results on 280 junior-high-school students where they compared their perceived digital literacy competencies and their actual performance in relevant digital tasks. Participants expressed high confidence in their digital literacy and overestimated their actual tested competence.

However, Tzafilkou et al (2022) developed and validated students’ digital competence scale based on self-reported data.

Asil et al (2014) used the 5-point Likert scale to collect data on measuring computer attitudes of young students in three separate factors: perceived ease of use, affect towards computers and perceived usefulness.

Hernández-Marín (2024) concludes that attitude scales have been consolidated as valuable elements in educational evaluation, allowing participants' perceptions of their learning to be compassionatesatisfactorily towardcaptured. self.Self-assessment Neffturns (2003a) argued that in orderout to experience self-compassion a person should be ablean exceptionally effective method for measuring attitudes. However, to monitorgain more perspective, complete and clearlyaccurate apprehendlearning, theirit ownis emotions, and use that informationnecessary to rapidly recover from painful experiences by transforming them into self-kindness and self-understanding (Neff, 2003). Therefore, this study’s results extend similar prior research (Şenyuva et al., 2011) which found that self-management and self-motivation are positively related to self-compassion and further suggestcomplement the crucialattitude rolescales ofwith theseother EI dimensions for experiencing self-compassion. methods.

In thistheir three-year longitudinal study, Lazonder et al (2020) followed the EIdigital dimensionliteracy progress of perception151 fifth and understandingsixth graders in their skills to collect, create, transform, and safely use digital information. They report that the children made the most progress in their ability to collect information. However, their capacity for generating information showed the smallest enhancement. “Development of emotionmost skills was moderately related, and it was independent of gender, grade level, migration background, and improvements in othersreading comprehension and maths. Children's socioeconomic status was notweakly relatedassociated to self-compassion. This could be because the applied Wong and Law (2002) OEA scale measures being perceptive and apprehending others’ emotions rather than using that information for influencing or managing others' emotions which is known to be usually positively related to self-compassion (e.g., Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2021). Also, this result is interesting from a developmental perspective since Maynard et al., (2022) study on an adolescent sample revealed a small but significant negative correlation (r = -.20**) betweenwith the ability to identifycollect and safely use information, but not with the emotionalother statestwo ofdigital othersliteracy and self-compassion. More specifically, their findings suggest that adolescents who demonstrate a heightened ability to perceive emotions in others, particularly negative emotions, experience lower levels of self-compassion and feelings of self-worth. Self-compassion varies depending on ageskills” (TaversLazonder et al.,al, 2024),2020, andp. it may be that the relationship between self-compassion and OEA and other EI dimensions may also be different depending on age, but this should be further investigated.

The other main finding of the study is that of the partially mediating role of the EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. Results indicated that a higher level of mindfulness leads to a higher perception of emotion in self, higher use of emotions for self-motivation and a higher level of regulation of emotion, which all lead to a higher level of self-compassion. Park and Dhandra (2017) found that the tendency of mindful individuals to be attentive, present-focused, and non-judgmental makes them more capable of understanding and managing emotions well and utilizing these emotions and knowledge to prevent self-critical thoughts. Self-compassion requires that one does not harshly criticize the self in times of difficulty (Neff, 2003a). Also, Bao et al. (2015) obtained that mindful people have a better ability to regulate their emotions and make use of their emotions to motivate themselves, which enables them to perceive less stress. In university students’ higher mindfulness and self-compassion were also related to less perceived stress (Martínez-Rubio et al., 2023). Thus, it seems that mindfulness via the mentioned EI dimensions ensures a more emotionally balanced mindset needed to experience self-compassion rather than over-identification with negative experiences.

The result of partial mediation suggests that there may be also other mechanisms through which mindfulness may increase student’s self-compassion. Also, they point to the direct beneficial effect of mindfulness on self-compassion. Neff (2003a) theorized mindfulness as a necessary precursor to a self-compassionate response since mindfulness enables mental distancing from ongoing difficulties so that feelings of self-kindness and self-understanding can arise. Mental distancing, i.e., decentering reflects a shift in perspective associated with decreased attachment to one’s thoughts and emotions (Biehler & Naragon-Gainey, 2022; Brown et al., 2015). It is further posed that through decentering mindfulness may exert positive psychological outcomes, both directly and indirectly by mobilizing other psychological mechanisms, such as cognitive flexibility, values clarification, self-regulation, and exposure (Brown et al., 2015).

In this study, we theoretically posited that dimensions of EI precede self-compassion. However, it is also possible that at least some of the dimensions of EI have a bidirectional and circular relationship with self-compassion. For example, a higher level of self-compassion may lead to higher self-regulation, since self-compassion decreases stress (Poots & Cassidy, 2020) and self-regulation is better when a person is not under stress. Thus, it may well be that the relationship between self-regulation of emotion and self-compassion is circular.

Limitations and practical implications

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow us to draw any conclusions about the direction of causality in the associations observed. Further, longitudinal studies are required to reveal the dynamic reciprocal nature of all the study variables. Second, this study focused on EI as a trait. Since EI may be conceptualized also as ability, future studies may focus on such conceptualization of EI.

Per practical implications, since previous studies suggested that mindfulness, EI, and self-compassion can be trained (Nelis et al., 2011; Smeets et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2019), educational institutions may include knowledge about these concepts and offer training to students in order to further increase their self-compassion1).

There

areConclusions

Thismany studyresearch showedresults in the literature which deal with the digital literacy of first grade primary school students. However, the research results of first grade primary school students' self-evaluation agree with the results of Lazonder et al (2020) in the part which states that dimensionsdigital literacy skills are independent of EI, i.e., perception and understanding of emotion in self, use of emotion for self-motivating purpose and self-regulation, mediated the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion, i.e., that higher mindfulness led to higher emotional intelligence, which in turn lead to higher self-compassion. These findings serve as the basis for directing greater attention of the educational process into the development of mindfulness and EI, especially dimensions of perception and understanding of emotion in self, use of emotion for self-motivating purpose and self-regulation, in order to promote students‘ self-compassion and, consequently, their readiness for the demands of the profession. gender.

Conclusion

Most of the respondents (over 87.5%) self-assess themselves as having acquired the required learning outcomes specified in the informatics curriculum for the first grade in the field of Digital Literacy and Communication.

There are no statistically significant differences in digital literacy of first grade primary school students by their gender or by their place of residence. The statistically significant differences were observed only in two items that contribute to digital literacy: more female respondents know the names of computer parts and more respondents coming from urban places of residence know how to search the Internet.

From an early age, students are using the Internet and there is a need to educate them to use it safely and responsibly. It is important to include and continue to teach the subject of informatics (computer science) in the initial grades of elementary school not only as an optional but as a compulsory subject.

It is important to continue to develop the digital literacy of students at an early age so that they can use information and communication technology safely and responsibly and that they are ready for new technologies and new occupations. The goal is also to achieve the equal representation of female and male students in university STEM study programs. The study presented in this paper shows that, at this early age, there are still no statistically significant differences in respondents’ self-assessed digital literacy by gender. However, there is a need to encourage female students in STEM subjects, such as informatics/computer science, to achieve the goal of equal representation of female and male graduates in the STEM fields.

Limitations of the research

The collected data is respondents’ knowledge self-assessment. The authors are aware that the respondents could overestimate their assessment, especially at their current age of six or seven. Actual testing of students’ knowledge would probably get more precise data.

The sample size is 104 and the representativeness of the results is limited.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Statement on the first publication of the research results

The results of the research presented in this paper have not been published before.

References

Baer,Ala-Mutka, R.Kirsti A.,(2011). Smith,Mapping G.Digital T.,Competence: Hopkins,Towards J.,a Krietemeyer,Conceptual J.,Understanding. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18046.00322

Ard W. Lazonder, Amber Walraven, Hannie Gijlers, Noortje Janssen (2020). Longitudinal assessment of digital literacy in children: Findings from a large Dutch single-school study. Computers & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13Education(1), 27–45.Volume 143, 2020, 103681.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911052835041016/j.compedu.2019.103681

Bao, X., Xue, S., & Kong, F. (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 48–52.

Biehler,Asil, K. M.,Mustafa & Naragon-Gainey,Teo, K.Timothy & Noyes, Jan. (2022)2014). Clarifying the relationship between self-compassionValidation and mindfulness:Measurement An ecological momentary assessment study. Mindfulness, 13(4), 843–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01865-z

Brown, D. B., Bravo, A. J., Roos, C. R., & Pearson, M. R. (2015). Five facets of mindfulness and psychological health: Evaluating a psychological modelInvariance of the mechanismsComputer ofAttitude mindfulness.Measure Mindfulness,for 6,Young 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0349-4

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M.Students (2003)CAMYS). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of PersonalityEducational andComputing Social PsychologyResearch, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cheng, X., Ma, Y., Li, J., Cai, Y., Li, L., & Zhang, J. (2020). Mindfulness51. and psychological distress in kindergarten teachers: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), Article 8212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218212

Di Fabio, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2021). The relationship of compassion and self-compassion with personality and emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, Article 110109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110109

Du Plessis, M. (2023). Trait emotional intelligence and flourishing: The mediating role of positive coping behaviour. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 49(0), Article a2063. https://doi.org/ 10.4102/sajip.v49i0.2063

Egan, H., O’Hara, M., Cook, A., & Mantzios, M. (2022). Mindfulness, self-compassion, resiliency and wellbeing in higher education: a recipe to increase academic performance. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1912306

Ewert, C., Vater, A., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2021). Self-compassion and coping: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12, 1063–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01563-8

Fong, M., & Loi, N. M. (2016). The mediating role of self‐compassion in student psychological health. Australian Psychologist, 51(6), 431–441.49-69. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.121852190/EC.51.1.c

Heffernan,Author M., Quinn Griffin, M. T., McNulty, S. R., & Fitzpatrick, J. J.1. (2010)2023). Self-compassionUnpublished Master’s Thesis.

Croatian Bureau of Statistics (2024). Students, 2022/2023 Academic Year. Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Zagreb, Croatia. Retrieved on 1.6.2024. from https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/arac4gkx/si-1726_studenti-u-akademskoj-godini-2022_2023.pdf

European Commission (2020-a). Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027 - Resetting education and emotionaltraining intelligencefor the digital age. Retrieved on 23.1.2024. from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0624

European Commission (2020-b). Factsheet - Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027. Retrieved on 23.1.2024. from https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/deap-factsheet-sept2020_en.pdf

European Commission (2022). DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Retrieved on 2.1.2024. from https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC128415

European Union. (2019). Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Retrieved on 21.1.2024. from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

García-Vandewalle, José, Marina García-Carmona, Juan Trujillo y Pablo Moya (2021). Analysis of Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) in nurses.Teacher InternationalTrainees: JournalThe Context of NursingMelilla, Practice,Spain. 16Technology, Knowledge and Learning 28 (2)(4),: 366–373.585-612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172x.2010.01853.1007/s10758-021-09546-x

Hollis-Walker,Godaert, E., Aesaert, K., Voogt, J., & van Braak, J. (2022). Assessment of students’ digital competences in primary school: a systematic review. In Education and Information Technologies (Vol. 27, Issue 7, pp. 9953–10011). Springer (part of Springer Nature). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11020-9

Hernández-Marín, J.-L., Castro-Montoya, M.-D., & Figueroa-Rodríguez, S. (2024). Alfabetización Mediática, Informacional y Digital: análisis de instrumentos de evaluación. Investigación Bibliotecológica: Archivonomía, bibliotecología E información, 38(99), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.22201/iibi.24488321xe.2024.99.58865

Jenny S. Radesky, Heidi M. Weeks, Rosa Ball, Alexandria Schaller, Samantha Yeo, Joke Durnez, Matthew Tamayo-Rios, Mollie Epstein, Heather Kirkorian, Sarah Coyne, Rachel Barr. (2020). Young Children’s Use of Smartphones and Tablets. Pediatrics July 2020; 146 (1): e20193518. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3518. Retrieved on 21.1.2024. from https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/146/1/e20193518/77025/Young-Children-s-Use-of-Smartphones-and-Tablets?autologincheck=redirected

Jun, S. J., Han, S. G., Kim, H. C., & Lee, W. G. (2014). Assessing the computational literacy of elementary students on a national level in Korea. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26(4), 319-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9185-7

Lee, L., Chen, D. T., Li, J. Y., & Colosimo,Lin, K.T. Bin. (2011)2015). Mindfulness,Understanding self-compassion,new media literacy: The development of a measuring instrument. In Computers and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Personality and Individual differencesEducation, 50(2),85, 222–227.84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.033compedu.2015.02.006

KalebićMerritt, JakupčevićK., Smith, K.D., & Di Renzo, J.C. (2014)2005). An Investigation of Self-Reported Computer Literacy: Is It Reliable? In Issues in Information Systems, 6(1), 289 – 295. https://doi.org/10.48009/1_iis_2005_289-295

Ministarstvo znanosti i obrazovanja Republike Hrvatske [Ministry of science and education of the Republic of Croatia] (2018). Odluka o donošenju kurikuluma za nastavni predmet informatiku za osnovnu školu i gimnazije u Republici Hrvatskoj [Decision on the adoption of the curriculum for the subject informatics for primary schools and high schools in the Republic of Croatia]. Retrieved on 2.1.2024. from https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2018_03_22_436.html

Nascimbeni, F. & Vosloo, S. (UNICEF) (2019). ProvjeraDigital ulogeliteracy metakognitivnihfor vjerovanja, ruminacije, potiskivanja misli i usredotočenosti u objašnjenju depresivnosti children. Retrieved on 21.1.2024. from https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/media/1271/file/%20UNICEF-Global-Insight-digital-literacy-scoping-paper-2020.pdf

National Ethics Committee for Research with Children (2020). Etički kodeks istraživanja s djecom [TheEthical roleCode of metacognitiveResearch beliefs,with rumination, thought suppression and mindfulness in depression]. (Doctoral disertation, Zagreb. Filozofski fakultet)Children]. Retrieved on 29th of March 202221.2.2024. from https://www.bib.irb.mrosp.gov.hr/713854istaknute-teme/obitelj-i-socijalna-politika/obitelj-12037/djeca-i-obitelj-12048/nacionalno-eticko-povjerenstvo-za-istrazivanje-s-djecom/12191

Lopes,Ólafsson, P.Kjartan N.& Livingstone, Sonia & Haddon, Leslie. (2014). Children’s use of online technologies in Europe. A review of the European evidence base. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. Revised edition.

Porat, E., Brackett, M. A., Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Sellin,Blau, I., & Salovey, P. (2004). Emotional intelligence and social interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264762

Martínez-Rubio, D., Colomer-Carbonell, A., Sanabria-Mazo, J. P., Pérez-Aranda, A., Navarrete, J., Martínez-Brotóns, C., Escamilla, C., Muro, A., Montero-Marin, J., Luciano, V. J., & Feliu-Soler,Barak, A. (2023)2018). HowMeasuring mindfulness,digital self-compassion,literacies : Junior high-school students ’ perceived competencies versus actual performance. In Computers and experiential avoidance are related to perceived stress in a sample of university students. Plos oneEducation, 18(2),126, Article23–36. e0280791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280791

Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Marin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.029compedu.2018.06.030

Mayer,Tzafilkou, J. D., Salovey, P.,Katerina & Caruso,Perifanou, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

Maynard, M. L., Quenneville, S., Hinves, K., Talwar, V.,Maria & Bosacki,Economides, S. L.Anastasios. (2022). Interconnections between emotion recognition, self-processes and psychological well-being in adolescents. Adolescents, 3(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3010003

McArthur, M., Mansfield, C., Matthew, S., Zaki, S., Brand, C., Andrews, J., & Hazel, S. (2017). Resilience in veterinary students and the predictive role of mindfulness and self-compassion. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0116-027R1

Neff, K. (2003a). Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2003b). The developmentDevelopment and validation of astudents’ digital competence scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005)SDiCoS). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and identity, 4(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021554

Park, H. J., & Dhandra, T. K. (2017). The effect of trait emotional intelligenceon the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and self-esteem. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0693-2

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448.

Poots, A., & Cassidy, T. (2020). Academic expectation, self-compassion, psychological capital, social support and student wellbeing.In International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101506

Pradhan, R. K., & Jandu, K. (2023). Evaluating the impact of conscientiousness on flourishingTechnology in IndianHigher higher education context: Mediating role of emotional intelligence. Psychological Studies, 68Education(2), 223–235.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-1186/s41239-022-00712-400330-0

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2010). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Rahe, M., Wolff, F., & Jansen, P. (2022). Relation of mindfulness, heartfulness and well-being in students during the coronavirus-pandemic. International journal of applied positive psychology, 7(3), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-022-00075-1

Schutte, N. S., & Loi, N. M. (2014). Connections between emotional intelligence and workplace flourishing. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 134–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.031

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personality and individual differences, 50(7), 1116–1119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.037

Şenyuva, E., Kaya, H., Işik, B., & Bodur, G. (2014). Relationship between self‐compassion and emotional intelligence in nursing students. International journal of nursing practice, 20(6), 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12204

Smeets, E., Neff, K., Alberts, H., & Peters, M. (2014). Meeting suffering with kindness: Effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(9), 794–807. doi:10.1002/jclp.22076

Tang, Y-Y., Tang, R., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Promoting psychological well-being through an evidence-based mindfulness training program. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, Article 237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00237

Tavares, L., Xavier, A., Vagos, P., Castilho, P., Cunha, M., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2024). Lifespan perspective on self-compassion: Insights from age-groups and gender comparisons. Applied Developmental Science, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2024.2432864

Thomas, C. L., Allen, K., & Sung, W. (2024). Emotional Intelligence and Academic Buoyancy in University Students: The Mediating Influence of Self-Compassion and Achievement Goals. Trends in Psychology, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-024-00363-6

Tran, M. A. Q., Vo-Thanh, T., Soliman, M., Khoury, B., & Chau, N. N. T. (2022). Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among Vietnamese university students: Psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators. Mindfulness, 13(10), 2574–2586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01980-x

Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243–274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1048-9843(02)00099-1

Zewude, G. T., Gosim, D., Dawed, S., Nega, T., Tessema, G. W., & Eshetu, A. A. (2024). Investigating the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between internet addiction and mental health among university students. PLOS Digital Health, 3(11), Article e0000639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000639

|

Odgoj danas za sutra: Premošćivanje jaza između učionice i realnosti 3. međunarodna znanstvena i umjetnička konferencija Učiteljskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Suvremene teme u odgoju i obrazovanju – STOO4 u suradnji s Hrvatskom akademijom znanosti i umjetnosti |

|

|

|

|

Sažetak |

|

|

|

Ključne riječi: |

|

|