Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in the Mathematics Teaching in Third Grade

Maria Petrova TemnikovaTrakia University Faculty of Education, Stara Zagora |

|

Professional paper |

Abstract |

|

The improvement of the efficacy of the pedagogical interaction during mathematics classes in Grade 1-4 is not only connected to the choice of strategies, technology, and methods of work of the teacher, but also to the learning styles used for acquiring the abstract educational content. The article covers different theoretical concepts related to the theory of studying through experience by Kolb who introduces four different cognitive styles of learning; problem production strategies of education and the problem-solving process. The paper presents specifics of researched methodical variants of work with different text tasks where solving involves Kolb’s experiential theory which can be applied in the education in mathematics in primary school. In the research work, reproduction and problem productive methods are applied such as problem exposition, heuristic, research and situational method, discussion, problem-solving discourse, solving of problematic tasks by analogy, and others. In respect of the results from the empiric research, mathematical-statistical methods are used for data processing. In the course of the empiric research two tests were applied: one for the determination of entry diagnostic and the other, after applying the new methodology system of work - for exit diagnostic of the knowledge, skills, and competencies of the Grade 3 students to solve text tasks. As a result of the applied new methodology system of work conditions for the four cognitive styles of learning were created which ensured the development of the knowledge and skills of the students to solve text tasks on a higher level. |

|

Key words |

|

cognitive styles of learning; mathematical text task; problem-productive strategy |

Introduction

In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak an emergency for international public health. The World Health Organization has expressed concern for the high riskmodernization of the spreadeducation in mathematics for a primary school in Bulgaria is a long and complicated process and is related to the replacement of COVID-19one educational paradigm with another. Changes covered the state educational policies, the program systems, the educational programs in countries aroundmathematics, the world.educational In March 2020,content, the Worldapproaches, Healththe Organizationmethods, evaluatedand thattechniques COVID-19for caneffective beeducation. characterizedTo achieve the educational goals, tasks and expected results specified by the state educational requirements as awell pandemic.as Theto Worldrealize Healthactive Organizationsubject-subject interrelation during mathematics classes in Grade 3, of great importance are both the strategies, and the publictechnologies healthapplied sectors aroundby the worldteacher are involved in preventingand the pandemic. However, this time of crisis is stressful for the entire population (WHO, 2020). Pandemics are rare, but they can devastating crises that can influence the lives of many children and their families physically, socially, and psychologically (Sprang and Silman, 2013). Oneknowledge of the vulnerablelearning groups, who had to adjust to the pandemic swiftly, are children and adolescents (Sharma, Majumder, and Barman, 2020). Children are not indifferent to the dramatic effectstyle of the COVID-19students. pandemic.

If experiencethe fear, uncertainty, physical and social isolation, and may miss school for a long time. Understanding their reactions and emotionsteacher is essentialfamiliar to accordingly meet their needs (Jiao et al., 2020). Sprang and Silman (2013) collected data from a sample of 586 parents and their children’s psychosocial reactions towith the pandemiclearning disasters. In data collection, they used a mixed methodology: questionnaires, focus groups, and interviews. The survey results showcased that a large number of parents (44%) who had been in quarantine or isolation reported their children as not needing mental health care services, while the reststyle of the parentsstudents (33.4%) reported that their children started to use mental health care services connected to their own experiences during or afterfrom the pandemic. The most frequent diagnoses for these children were acute stress disorder (16.7%), adjustment disorder (16.7%), and grief (16.7%).

An early studyage of behavioral7-11 andyears, emotionalthen reactions of Chinese children during the COVID-19 epidemic was conducted in the Chinese province of Shaanxi. Given the restrictive measures of movement brought by the Chinese government to stop the further spread of COVID-19, parents filled out an online questionnaire about their children’s behavioral and emotional responses to the epidemic. The survey results of a sample of 320 children aged 3 to 18 years old showcased excessive parental attachments, distraction, irritability, and fear of asking questions about the epidemic as the most common behavioral and emotional problems. Furthermore, the results demonstrated excessive parental attachment and angst for possible infection of family members as symptoms more likely to develop in kindergarten children aged 3 to 6 years old (Jiao et al., 2020).

A study conducted on a sample of 1143 parents and children from 3 to 18 years of age, which analyzed immediate psychological effects of COVID-19 quarantine on Spanish and Italian youth, showcased that as many as 85.7% of parents noticed emotional and behavioral changes in their children during quarantine. The most frequent symptoms were concentration difficulties (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), feelings of loneliness (31.3%), and worry (30.1%) (Orgilés, Morales, Delvecchio, Mazzeschi, and Espada, 2020).

In their paper, Imran, Zeshan, and Pervaiz (2020) present the most prevalent symptoms of stress in young children during the pandemic. Young children most often exhibit stress in disapproval and irritability, inability to concentrate, as changes in sleep patterns, in waking up during the night, having nightmares, and in various regressive behaviors (such as thumb sucking, not controlling urination, and/or defecation, and demanding to be carried). In conclusion, the authors state that interventions should focus on nurturing resilience in children and adolescents by encouraging structure, routine and physical activity, and better communication to address children’s fears and concerns.

The 2020 study titled How does the COVID-19 pandemic affect the mental health of children and adolescents?, summarized relevant and available data on the mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing 51 topic-related articles. As expected, results determined different responses to stress in a different developmental stages. Yet, children of all developmental stages showcased a higher rate of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptoms, as would be expected after any highly traumatic occurrence (Marques de Miranda, da Silva Athanasio, Cecília de Sena Oliveira, and Simoes Silva, 2020).

In the United States, a nationwide survey was conducted in June 2020. Given the pandemic, the survey aimed to determine changes in the physical and emotional well-being of parents and their children. The results showed that 27% of parents reported deterioration of their mental health, while 14% reported their children’s behavioral problems as worsened. The deteriorated parents’ mental health coincided with children’s worse behavioral problems in nearly one in ten families (Patrick, Henkhaus, Zickafoose, Lovell, Halvorson, Loch, Letterie, & Davis, 2020).

Quarantine due to COVID-19 has had effects on the lives of most children and adolescents. They replaced friendships and routines of going to kindergarten or school with virtual social meetings and classes. Outdoor leisure was bound to the indoors. Closing-down was imperative to fight the pandemic, but the halt on social contact and the ban of going outside can have immediate psychological effects on children and adolescents. There were some public debates about whether the quarantine will affect children or whether theyhe will be able to adjustrecognize its strong sides. In this way, he will have the chance to apply suitable methods in order to compensate for its weak sides thus assuring higher efficiency of the learning process. Consequently, this facilitates the process of forming skills in the students to show flexibility and to apply their knowledge in non-standard conditions during solving creative mathematical text tasks. The basis for development by the teachers of efficient strategies for teaching and learning the educational content in mathematics is the recognition of the individual learning style of the students. According to Fielding (Fielding, 1994), the inconsistency between the learning style of the student and the teaching approach adopted by the teacher will have a highly negative effect on the overall learning process.

After analyzing foreign and Bulgarian publications, it was found that there are different developed models of learning styles. “More than 70 theories related to the newlearning environmentstyle withoutare excessiveknown.” emotional(Felder, strain.1996, Knowledgepp. about18-23) theAmong effectsthem quarantineare has on the psychological welfarethose of childrenCorno wouldand aid professionals in implementing preventive measuresSnow (Orgilés1985), Entwistle (1981, 1991), Entwistle and Ramsden (1983), Griggs (1991), Hudson (1966), Pask (1976), Riding (1997), Riding and Chema (1991), Witkin et al. (1977), 2020).etc. The learning styles are also studied in Bulgarian sources including the related cognitive styles: Doncheva (2017), Ivanov (2004), Krumova (2018), Lecheva (2009), etc.

One of the definitions of a learning style belongs to the NASSP (the National Agency of Secondary School managers in the USA) which states that: “the learning style is a composition of cognitive, affective and psychological characteristics which are relatively stable indicators of how the student perceives, interacts with and responds to the educational environments.” (Grigss, 1991, p. 2) There must be a differentiation between the cognitive learning style and the learning styles in general as the first concept has a narrower scope.

Some researchers like Griggs (1991), Keefe (1979), and Riding and Chema (1991) include problem-solving in the characteristics of the cognitive learning style. According to Keefe (Keefe, 1979, pp. 1–17), the cognitive style is “the typical way for processing of information by a person – perception, thinking, memory and problem-solving.” For Riding and Chema (Riding, Chema, 1991) this style is the normal approach to problem-solving, thinking, perception, and memorizing of information.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) defines the current time as an increased stress-and-crisis time, stating that children are expected to be more demanding and needing more attention from their parents. Moreover, the World Health Organization recommends honest and age-appropriate conversations to ease their children’s anxiety. Overall, the knowledge base on children’s reactions to trauma and disastrous events is expanding, but the descriptions of their reactions during epidemics remain scarce (Klein, Devoe, Miranda-Julian, & Linas, 2009).

Given the previous research on psychosocial, behavioral, and emotional reactions of children during the COVID-19 epidemic – which results, due to the movement-restriction measures implemented to prevent further infection spread of COVID-19, were collected by parents filling out online surveys – this paper aims to research children’s perception on state of emergency caused by the Coronavirus. This research will use focus groups of children aged 4 to 6 years old as the method, bearing in mind the children’s expressed fear of asking questions about the epidemic (Jiao et al., 2020) and the World Health Organization’s advice of honest and age-appropriate conversation to alleviate stress and anxiety (WHO, 2020). Focus groups create a safe peer environment for children; the method can help avoid some power imbalances between researchers and participants, such as those between an adult and a child in a one-on-one interview Shaw, Brady, & Davey, 2011). Focus groups not only give researchers a large amount of data on a particular topic in a relatively short time but also encourage discussion and ask participants to explore and clarify their views (Clarke, 1999). It is an increasingly popular research method suitable for collecting data from children, young people, and parents (Adler, Salantera, and Zumstein-Shah, 2019). The goal of effective, or guided, focus groups are to express children’s voice and point of view on various topics (Kelly, 2013), and so the goal of the paper is to examine children’s perception of the state of emergency caused by the COVID-19 epidemic by the self-representation of participants used in the focus group research method.

Method

Participants

The participants were eight children from a kindergarten in Osijek-Baranja county. Children participated in a guided group discussion, in two focus groups on the 12th and 13th of May 2020, which was the first week in which children could return to the kindergarten after all of them closed down in the Republic of Croatia from 16th of March 2020 to 11th of May 2020. The age of the children ranged from 4 years to 6 years, and on average 5 years old (59 months). Three girls and five boys participated in the focus groups. The sample was convenient.

Procedure

The parents of all participants and participants themselves were familiarized with the objectivespurpose of the research andwork is to outline the parentsmain gavecharacteristics writtenof consents.Kolb’s Childrenexperiential werelearning informedtheory and to describe some of the ways of its application during the education in mathematics in Grade 3 for solving text tasks.

Literature review

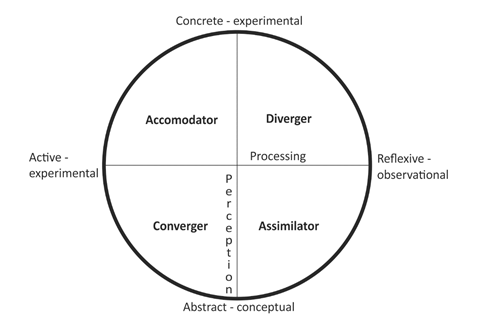

For the purposes of developing the model of experiential learning Kolb steps on the research aimsworks of Jung, Dewey, Lewin, and werePiaget. askedAccording aboutto understandingFielding (Fielding, 1994, p. 395), “he goes beyond the bipolar approach of Witkin, Hudson, and Pask and argues for a fourfold model which incorporates differences in the ways individuals perceive or grasp the nature of experience and then process or transform it.” Kolb (Kolb, 1984, p. 38) summarized that „learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience.“ An important feature of his theory is the conclusion that learning is a cyclic process. The stages follow one after the other in sequence – concrete experience (CE), reflexive observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimenting (AE) – and the students must systematically go through them.

Behind the concept of cycle “lay two primary axes: an abstract conceptualization-concrete experience (AC-CE) dimension and an active experimentation-reflective observation (AE-RO) dimension. These reflect the two main dimensions of the learning process that correspond to two major ways by which we learn. The first is how we perceive or grasp new information or experience, and the second is how we process or transform what waswe explainedperceive.” (Healey, Jenkins, 2000, p. 187)

Kolb’s cycle includes four stages related to them,different learning styles that reflect students’ preferences in the way they receive and process information. The learning styles identified by him are related to different approaches for problem-solving which are embedded in every text task from the education in mathematics in Grade 3.

Healey and Jenkins (2000) adapted the characteristics of Kolb's learning styles outlined by Kolb (Kolb, 1984, p. 86) and Gibbs (Gibbs, 1988, p. 20) and consider the effect which they gavehave informedon verbalthe consent.education in Childrengeography werein informedUniversities.

Ivanov (Ivanov, 2004, p.30) wrote that “divergers are students who perceive concrete information and reflectively process it and also they couldneed stopto participatingbe personally engaged in the researchcognitive activity. Convergers are students who perceive abstract information and reflectively process it. They also perform detailed, consistent steps in thinking and learning. Assimilators are those students who perceive abstract information and actively process it. They need to be drawn to pragmatic solutions to cognitive problems. Accommodators are students who perceive concrete information and actively process it. They must be drawn into risky, experimental, and flexible cognitive activities.”

According to Kolb (1984), the following types of students were specified – concrete-experimental, reflective-observational, abstract-conceptual, and active-experimental.

Figure 1. Type of students and learning styles according to Kolb

Mihova (Mihova, 2002, p. 79) described the four learning styles: “Accommodative style (accommodators): а combination between concrete-practical and active-experimental styles. The representatives of this style have the ability to learn directly from experience … and do not refuse to be included in new and unknown educational situations. They are able to search for the meaningful and the important in the educational experiment, consider the options on how to proceed, and take into account what others have done in this situation before them. They deal well with complex problems and are able to see the relationship between given components. This type of student prefers indirect strategies for education which enables them to take the role of researchers and knowledge seekers.”

In the problem-solving process, they rely more on other people than on their own analysis. The teachers who work with such students shall use various methods of education but must always keep in mind that the accommodators want to be active participants in the educational process.

Assimilative style (abstract conceptualization, reflexive-observational). This is a style based on logic, a combination of abstract-conceptual and reflexive-observational styles. This type of student has preferences for the exact and logically presented information and not its practical value. The random and aimless studying of problems for them is a waste of educational time. They require the teacher to be an expert and prefer the educational information to be visualized by demonstrations. These students are the least provocative to the teacher. They tend to follow punctually the teacher if he is approachable and able to answer their questions.

Divergent style (concrete experience, reflexive observation). This style is a combination of the concrete-experimental and the reflexive-observational types. The students who have this learning style prefer to think about a concrete situation and understand what this situation offers them. They would like to receive information in well systematized and structured form. The children are interested in how and to what extent the knowledge they receive is related to their experience and personal interests. This type of student is very good at anystudying moment.a Bothparticular focussituation groupsfrom lasteddifferent approximatelyangles. 20Their minutes,approach ledto the situation is to do more observation than taking an action. They identify the problems, see new ways of doing the things, and new and creative solutions to the problems. They have an overall view of a situation and present their ideas in an innovative and artistic way. The teacher must actively communicate with the students, answer their questions, and dive into proposals. It will be good to use manuals, recommendations, instructions, and abstracts. Flexible and varied thinking is recommendable.

Convergent style (abstract conceptualization, active observation). This is a practical style, a combination between the abstract-conceptual and the active-experimental types. This type of student is oriented toward finding the practical application of ideas and theories. They positively assess the opportunity to work actively on well-structured educational tasks and prefer learning on a trial and error basis in a safe environment at school. The efficient teacher for them is the one who is an instructor and from whom they receive practical directions and timely feedback. They define and solve problems, make decisions and work well alone. They also are characterized by deductive thinking. These types of students are good at formulating goals, planning their activities, and knowing how to find the information. They see the applicable aspects of the theory and their work is very well structured.”

The diagnosis of students’ learning styles is of prime importance for this research work. According to Griggs (Griggs, 1991, p. 3), there are “three instruments for assessing a learning style.” The Learning Style Inventory-Primary Version (Perrin, 1981) for children in kindergarten through grade two is a pictorial questionnaire.

Methods

The below presentation offers different ways to apply Kolb’s theory in the context of the education in mathematics in Grade 3 for solving mathematical text tasks.

The first stage of the learning process – the concrete experience – is based on the experience gathered by the research protocolstudents in theGrade kindergarten1 rooms.and Grade 2 for solving ordinary text tasks whose solution requires only one arithmetic operation and composite text tasks in Grade 2 whose solution requires two arithmetic operations. 1. At this stage, the beginningteacher, using the method of discussion update the knowledge, skills, and the acquired cognitive experience of the discussion,third childrengraders receivedregarding puzzlesthe totext playtasks withdescribed becauseabove.

During researchersthe noticedsecond thatstage giving(the childrenstage puzzlesof duringreflexive discussionsobservation) madean them more relaxed, prompting them to have betterintellectual and richerpersonal answers to the research questions (Morgan, Gibbs, Maxwell,reflection and Britten,self-reflection 2002).

Thetaking researchpart protocolin consisted of nine questions. At the beginningrespect of the conversation,ways childrenof weresolving askeddifferent antypes introductoryof question:text Willtasks. youThis talkis toaimed meat a bit and solverevealing the puzzle?, and then the transitional question: Do you know why you haven’t been to the kindergarten lately? Key questions followed: What is a virus? How can it harm us? Do you know how we get this virus? Can we do something not to get it? Have you talked to somebody about coronavirus? Are there any places you used to go to, but now you cannot becausemeaning of the virus?mathematical Lastly,operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division; at revealing different relations between numbers; at revealing the childrenconnections were askedbetween the finalcomponents question: Are you interested in anything else aboutand the coronavirus?results Youfrom the four arithmetic operations. This stage can askbe mereferred anyto questionas ifthe youfirst want.

Contentof analysisthe resultsprocess andof discussion

solving Thea text task (understanding the content of the audiotask) recordingsdefined wasby listenedD. Poya (Poya, 1972). Under the lead and the supervision of the teacher the third graders reverse back to their experience and transcribedperform analysis and synthesis to assess the suitability of the chosen way for solving the task. They also consider the possibility of more rational and easier ways to solve the task and if such are found, then how to apply them. The teacher is using the computermethod programof Nvivo.discussion Qualitativeand contentapplies analysisthe inductivelymethods developedof discussion and heuristic discussion through which he directs the students towards clarification of ways used to solve text tasks and to analyze the reasoning, and the performed activities.

During the third stage (abstract conceptualization) the students formulate a different hypothesis for solving the problem situations imposed by the text tasks. The teacher applies the productive method modeling and supports their work with auxiliary models. There are the following categories:options 1. Knowledge offor the virus, 2. Knowledgecreation of the preventivemodels: measures,they 3.are Communicationcomposed aboutafter the virusanalysis of the content of the text task done jointly by the teacher and the students. After that, the student fills in the numerical data in the model by themselves or with the assistance of the teacher using the method discussion (a reproductive discussion or a discussion with elements of heuristic).

During the fourth stage (the stage of active experimenting) the third graders work on the second step (analysis of the solution and composition of a plan for solving the task) and on the third step (execution of the plan for solving the task) of the process for solving a text task as defined by Poya (Poya, 1972). The students analyze the proposed way of solving the task (namely the mathematical numerical expressions), 4.and Emotionsthey determine if any changes are needed or if there are any mistakes. They also discuss any other possible options for solving the task in question. The teacher applies the method of problem-productive exercise and exercise on analogy

In the methodology work problem-productive (indirect) strategies of education were applied. They are directed to the creation of pedagogy conditions for effective work in respect of generating ideas, applying solutions, research, proving, planning and assessment during the epidemic,process 5.of Strategiestask solving by students. The main characteristic of this process is the transfer of already acquired the students’ knowledge and skills for dealingsolving tasks in new, creative situations or in a familiar situation to find new knowledge. Private-methodical/mathematical, developing, heuristic and person-oriented technologies of education are used.

The technology of education is oriented to a particular subject. It is also educational, informational, developing, and self-developing. The competency approach, the system-acting, the researching, the reflexive, the interactive, and the human-personal approaches are important components in its procedural side. The choice of the concrete method by the teacher depends on the concrete educational content related to solving text tasks, the stage of Kolb’s cycle, and the learning styles of the students. They perform activities on reproductive and productive-creative levels.

One of the composite text tasks which the Grade 3 students solve is given below:

The Ivanovs family saved 1345 lv. They bought a washing machine for 610 lv and a dishwasher for 476 lv. How much money they had left?

During the first stage (the stage of concrete experience) the experience gathered by the students so far relates to solving simple or composite text tasks aimed at clarifying the meaning of the operations addition and subtraction as well as at writing the solution of the task in two ways and namely with negativethe emotionsuse of two numerical expressions or with one numerical expression with brackets.

During the second stage (the stage of reflexive observation) the students reflect on ways to solve these types of tasks using their own experience.

During the third stage (the stage of abstract conceptualization) the teacher applies the method of problem-productive exercise through which the known and the unknown objects in the text tasks are getting identified. Students present their own hypotheses in reply to the imposed questions and make an abbreviated record of the task thus facilitating the transition from the external to the internal structure of the task.

If during their work in the epidemic.fourth Thestage tableof Kolb’s cycle the third graders determine only one of the ways to solve the task, the teacher using a heuristic discussion with them shows anthe example of data organization, and in thissecond way of data analysis,solving the conversationstask as well. The problem-productive strategy of education applied by him helps the students to solve the problem situation embedded in the text task. The differences in the analytic-synthetic way of reasoning of both solutions are discussed.

Table 1

Solution of the focus groups are concise and structured for a more easy interpretation.

Results

Example of data organization 1task

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

KnowledgeGoing through the four stages of Kolb’s model helps to improve students’ knowledge and skills to perform analytic-synthetic reasoning and to search for more than one solution to a given text task.

One of the COVID-19types virus

of text tasks according to the Rogier’s (Rogiers, 1985, pp. 229–234) classification is the so-called “open” task. For this type of task students independently search for all or for some numerical data and also allow different answers.

ABelow telephoneis survey,an conductedexample of how the work on one of the “open” tasks from Aprilthe methodology system shall be carried out, which was used in the study:

Stage 1 (CE): The work starts with updating the concrete experience of the students in respect of traveling (family trips or traveling with their classmates) in the country along different routes. They share details of their trips and namely which town their traveling started from, which towns they passed through and where their trip ended. They recall the algorithms of work used so far and the specifics of the activities related to Maydata 2020collection from different sources.

Stage 2 (RO): The teacher divides the students into teams of 3 and 4. They do reasoning on questions like If we pass through other towns in the country, what will change (parameters like length in kilometers of the route and the traveling time).

Stage 3 (AC): The teacher presents different routes from the Town of Stara Zagora to towns in East-West, North, and South Bulgaria. One reliable tool to assist the students is a map on the wall where all optional routes are schematically marked.

Stage 4 (AE): Each one of the teams receives the task to compose and describe the different routes from the Town of Stara Zagora to another town in the country (for example, the Town of Varna in East Bulgaria); collecting data for the distance of the route in kilometers and to write it down on a sampleworksheet prepared by the teacher in advance. This is the first problem task that students must solve.

There are two options for the teacher to do his methodology work. The first option is to combine two organizational class-lesson forms of 241education children– agedexcursion, 10and lesson. The excursion is organized to 17a yearsrailway old,station obtainedor a bus station. The students shall be informed about the followingpurpose results.of Allit in advance as well as about the tasks which they have to work on. From the timetable and other sources, they collect information about the duration of the trip by train or by bus between the towns in question and write it down in their worksheets. Using other sources of information designated by the teacher the students also collect data about the distances between the towns. This practical productive work helps the students to develop skills for collecting information from different sources. The second option is to use only one organizational form and namely a lesson in a class environment.

Stage 5 (CE): The students present the routes developed by them as well as the data they have collected for these routes – the distance in kilometers and the traveling time between the towns.

Stage 6 (RO): The third graders divided into groups to discuss different questions that arose during their presentations.

Stage 7 (AC): Considering the chosen routes the students formulate and present hypotheses about the different types of text tasks they may compose – text tasks to reveal the meaning of the mathematical operations addition and text tasks from different comparisons using the operations addition and subtraction.

Stage 8 (AE): The teams compose text tasks using the collected data and consequently solve them. They present these tasks to the class and discuss them. At this stage, students solve problem situations through composing text tasks.

“The students’ interest is provoked by the fact that they feel the need of diverse perception and actions leading to various emotional experiences while traveling and interacting with the surrounding world.” (Zheleva-Terzieva, 2019, pp. 21–28)

The productive methods used by the teacher in his methodology work are problem-seeking exercises, exercises of creative character, problem-seeking (heuristic) discussion, problem-seeking practical work, solving problem tasks by analogy, and heuristic (partial-research method), modeling, etc.

Through the above-described process solving of the “open” task, the students with accommodative learning styles can be included in new and unknown educational situations where to think over how to proceed. The teacher shall apply an indirect (problem-productive) strategy of education which is preferred by this type of student. The exact and logical presentation by the teacher during his joint work with the students corresponds to the preferences of the students with assimilative learning styles. The motivating presentation of the cognitive problems to them will facilitate their active participation in the process of problem-solving, otherwise, they will grudgingly participate in a random and aimless study of such problems. For students with divergent learning styles is important to study the situation in the “open” task from different points of view. They identify the problems in the task and produce new and creative solutions. The students with convergent learning styles define and solve problems during the process of working with the task. Assigning them to work on their own facilitates the use of the "strong" characteristics of their learning style. Students formulate the goal, plan their work and successfully find the necessary information related to the traveling routes.

The experimental work was carried out with students from Grade 3 of the Second Elementary school Petko Rachov Slaveykov in the Town of Stara Zagora for the period 2015 to 2021. To identify the learning style of the Grade 3 students subjected to the research, the “Kolb’s Styles” Questionnaire was used. This is a methodology for researching the way students prefer to study the educational material. The Questionnaire contains 9 questions every one of which has got 4 answers to choose from.

Results

For the purposes of the experimental work, two tests have been used. One of the tests was for the entry diagnostic of the students and was applied at the beginning of the school year. The second test was for the exit diagnostic of the students and was done after applying the new methodology system of work. The researcher studied some of the qualities of the two tests such as their difficulty and separating force of the tasks in the tests. Each one of the tests consists of eight tasks. The first task is of ordinary nature while the second and the third tasks are composed of text tasks that need their solving up to 3 calculations with direct use of relations. The fourth task is also a standard task. The fifth and the sixth tasks are again composed tasks however with indirect use of relations. The seventh task requires students to compose a text task by given numerical data. The eighth task requires the same but students must compose the text task using a schematic auxiliary model (drawing).

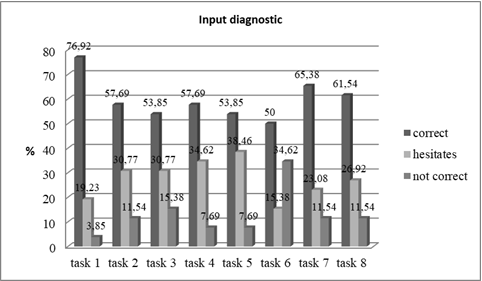

The results from the entry diagnostic are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Entry diagnostic of Grade 3 students’ knowledge and skills to solve text tasks

They demonstrate that the third graders have acquired the knowledge and the skills needed to solve both standard text tasks using only one calculation and composed text tasks that need up to two calculations for their solving with direct use of the relations “with … more than …”, “with … less than …”, “… times more than …” and “… times less than …”. The entry diagnostic test helped to find out that …% of the students can compose text tasks by a picture with numerical data, numerical expression, and table.

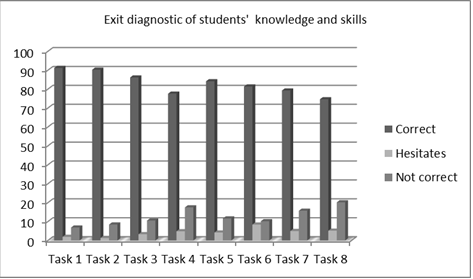

The exit diagnostic is done in 2021 and the results are presented and analyzed graphically in the below diagram (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Exit diagnostic of Grade 3 students’ knowledge and skills to solve text tasks

As a result of the experimental work, it was found out that after the exit diagnostic 91, 23% of the third graders using numerical expressions correctly model situations described by the direct use of the relation “with …. more than ….”. 8, 42% of the students make mistakes when model situations described by the direct use of the relation “with … less than ….”. 86,16% of the students correctly solve text tasks with indirect use of the relation “with …. more than …”. 17,52% of the students make mistakes when solving text tasks with indirect use of the relation “with … less than ….”. Using numerical expressions 84,16% of the students correctly model situations described by direct use of the relation “… times more than …”. 10,18% of the students make mistakes when using numerical expressions for modeling situations described by direct use of the relation “… times less than …”. 79,28% of the third graders correctly solve text tasks with indirect use of the relation “… times more than …”. 20,16% of the children didmake knowmistakes aboutwhen coronavirus,solving buttext onlytasks halfwith (57%)indirect knewuse of the relation “… times less than …”. The difference in the results was proved to be statistically significant.

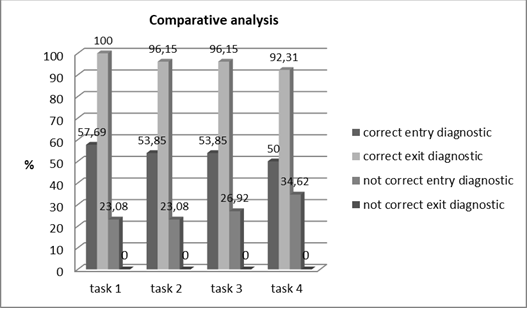

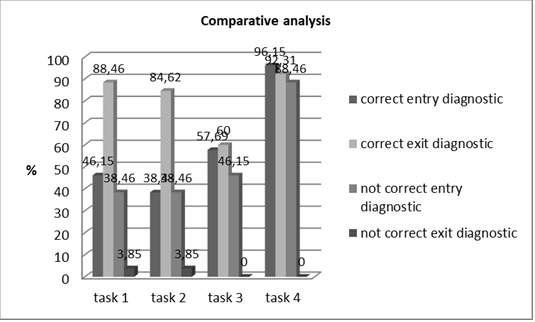

The following two diagrams graphically present the data from the comparative analysis between the entry and the exit diagnostic of the knowledge and the skills of the third graders to solve text tasks.

Figure 4. Comparative analysis between the entry and the exit diagnostic of the knowledge and the skills of the third graders to solve text tasks

The data in Figure 4. show that it was a virus that can cause serious illness. This raised concern givenbetween the factrespective thatshares COVID-19of the students subjected to the study there is a highlystatistically infectioussignificant virus.difference The survey results were surprising because they showcased that children of rural areas (61%) knew more about the virus than the children of urban areas (53%) (Sithon, 2020).

In this study, all eight children were familiar with coronavirus – they knew that they did not go to the kindergarten due to its outbreak and showed knowledge that the virus isseen in the wholeresults world:from It’sthe aentry diseaseand the exit diagnostic in therespect city…inof alltheir cities.skills Additionally,to assolve itstandard wastext notedtasks inwith the aforementioned research in which the children perceived the virus as dangerous (85%), this research as well reported children perceiving the virus as highly dangerous: I could get infected, be sick,direct and goindirect to the hospital. Furthermore, children knew that the virus is infectious to both children and adults, and some even mentioned pets.

Researcher: Tell me, can this virus infect children?

Girl: Yes, kitties too.

Researcher: What do you think, for whom the virus is the most dangerous?

Girl: For a little baby.

Researcher: Do you think that it is more dangerous for a little baby or grandmas and grandpas?

Boy: For grandmas and grandpas.

Knowledgeuse of the preventiverelations measures

“with … more than …”, “with … less than …”, “… times more than …” and “… times less than …”. (First criteria, 1., 2., 3., and 4. Indicators)

InBelow thisare study,presented childrenthe listedcalculations severaland preventivethe measures.comparison Forof instance,the theyrespective listedshares stayingof parameters studied during the work with the experimental class at home, that is, minimizing the risk of infection: We have to protect ourselves, be at home. Apart from not being exposed to the virus, children noted hygiene habits and disinfectants: That we are at home, and I have disinfectants in the carbeginning and at the bed.; We have to wash our hands.

In research from Cambodia (2020), the majorityend of the childrenstudy.

For Task 1:

U calc. = 6, 188 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (99.2%α) listedtable hand-washing= and2,06

For mask-wearingTask 2:

U calc. = 4, 0026 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (80.1%α) astable a= preventive2,06

For Task 3:

U calc. = 4, 105 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (Sithon,α) 2020).table In= this2,06

For noTask child4:

mask-wearing asU acalc. preventive measure= against4, coronavirus,038 however,for accordingα = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

The data in Figure 5. show that between the respective shares of the students subjected to the recommendationsstudy there is a statistically significant difference seen in the results from the entry and the exit diagnostic in respect of their skills to solve composed text tasks requiring up to 3 calculations with direct and indirect use of the Croatianrelations Institute“with of… Publicmore Health,than children…”, from“with kindergarten… childrenless afterthan …”, “… times more than …” and “… times less than …”. (Second criteria, 1., 2., 3., 4. and 5. Indicators)

Figure 5. Comparative analysis between the second year to early-school years are not obligated to wear masks. Appropriately, these children do not even perceive them as a preventive measure.

Communication about the COVID-19 virus

Communication with kindergarten children about the infections spreadentry and the explanationexit diagnostic of the diseaseknowledge should not only includeand the simplification of language and concepts but should also take into account children’s understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and diseases. From 4 to 7 years of age, children’s comprehension is under the influence of magical thinking, characterized by a child’s belief that thoughts, wishes, and unrelated actions can cause certain events. For example, a child can believe that specific thoughts or behavior can cause illness. Adults have to be aware of children’s developmental stages and be careful in explaining diseases so children would not unjustly blame themselves or feel as if the disease is a punishment for their misbehavior (Edwards and Davis, 1997). Thus, listening to children’s perceptions and beliefs about COVID-19 is crucial to provide them an accurate explanation that they can understand without unnecessarily feeling guilty or scared (Dalton, Rapa, and Stein, 2020). In this research, and regarding communication and information about coronavirus, children state their conversations with primary caretakers, relatives, and kindergarten teachers: I talked a little with mom and dad, they say you shouldn’t go out for the corona.; Yes (I talked), with mom, dad, grandma, and grandpa .; Kristina (kindergarten teacher) talked about it. In a study by Sithon (2020), the majorityskills of the childrenthird reportedgraders socialto mediasolve andtext newstasks

For primaryTask sources5:

coronavirus information,U whilecalc. fewer children= reported3, their889 families.for Givenα = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

For Task 6:

U calc. = 3, 647 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

For Task 6:

U calc. = 3, 801 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

For Task 7:

U calc. = 4, 367 fpr α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

For Task 8:

U calc. = 3, 647 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

For Task 9:

U calc. = 4, 105 for α = 0,05 probability for mistake U (α) table = 2,06

The reasoning demonstrated by the ageGrade of3 thesestudents research participants, it is logical to assume communication with caretakers and family as a primary source of information because they are not yet able and not being age-appropriate for them to collect information from news or social media.

Emotions during quarantine

Long periods of quarantine can cause an increase in anxiety, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, isolation, and insomnia in children (Roccella, 2019). Children are vulnerable toon the emotionalperformed effects of traumatic events, especially those that result in the closing of schools, social distancing, and house quarantines (Lubit, Defrancisci, and Eth, 2003). From statements of children in this study, it is evident that children articulated their emotions regarding the restrictive measures: I was sad because I couldn’t go outside.; I was sad because I didn’t go to kindergarten but I didn’t cry. Time of COVID-19 pandemic is a very unusual time for humanity, but especially for children that had to face huge life changesactivities during the Coronatask-solving crises.process Inshowed the lineimprovement of preventivetheir measures,reflexive schoolsskills. These skills are getting piled up and kindergartens were closed down, which deprived children of a sense of structure, routine, incentives provided by educational institutions, and the feeling of social support from peers, educators, and school teachers. It is very likely that in this time, children will feel concerns, anxiety, and fear, i.e. types of fear often felt by adults, which include fear of death, fear of relatives dying, and fear of receiving medical help. As stated on the World Health Organization’s website (WHO, 2020), all of this contributes to the potential threat to mental health and children’s psychological resiliencedeveloped during the pandemic.process Theseof exact fears were felt by childreneducation in thismathematics research,and asrepresent ita iscomplex evidentsystem of knowledge, skills, relations, self-control, self-development, self-assessment, etc. Students upgrade the skills in aquestion statementwith every next stage of atheir four-year-oldeducation. boy:Teachers Imust missedbe myfamiliar grandparents because I didn't go to them because I was afraid I would infect them if they didn't die. This sentence showcases that extremely young children felt fear of infection and death while experiencingwith the new normal in which they missed their loved ones whom they otherwise often saw. In addition to the fear of death, it could be observed that the children are worried about stopping the virus and that they are aware that the time of Corona crises could last.

Researcher: Do you think coronavirus is gone, and won’t come back?

Boy 1: But, they said that it will, during fall.

Girl 1: No, during winter

Girl 2: It passed a little.

Researcher: It passed a little, but it’ll come back?

Boy 1: Yes, but during winter, it won’t come back during summer. I guess Corona will go all the time now.

Boy 2: It will never pass.

Strategies for dealing with negative emotions during the epidemic

From the statementssteps of the childrenKorthagen in this research, it is noticed that they listed playtime as leisure time during quarantine: I was bored, so I played. Naturally, this is not surprising, given that in play children test various states, moods, and emotions. Play is seen as a form of "emotional hyperventilation." In the play, through "emotional hyperventilation," children play with feelings of fear, anxiety, and abandonment (Wood, 2010). Play is exceptionally important in a life of a child because it is more than just fun. It is a valuable part of the intellectual, social, and emotional development of the child (Petrović-Sočo, 1999), and so in times of crisis, play can help children deal with stress, anxiety, and crisis-related trauma (Chatterjee, 2018).

Graber et al. (2020) reviewed the worksmodel related to the effectprocess of development of reflexive skills and namely action, looking back to the action, understanding the main aspects, creation of alternative methods of action, and testing which is a new action itself and consequently, a starting point of a new cycle.

The empiric study presents an observation and the results of it are introduced in two observation protocols – the first protocol relates to the entry diagnostic and the second one – to the exit diagnostic. The information in the protocols reflects the correctness of the quarantinestudent’s reasoning and restrictiveexplanations measuresregarding the activities performed by them during the four stages of the text task solving process – reasoning on child’sthe playtext task content, making a plan for its solving, execution of the plan and healthlooking well-being.back Theyto identifiedthe whole process completed so far. The main reasoning is getting performed exactly at this last stage. The results received from the test show that the correct reasoning increased from 20% to 34%.

Conclusions

Based on the results of the research work the following topicsconclusions can be made:

After completing the longitudinal research, it was found that relateKolb’s model of experimental learning can be successfully applied not only in University education but also in the education in mathematics for Grade 3 of Primary school.

After applying the developed methodology system of work the following was achieved:

- systematic transition through Kolb’s four stages (concrete experience, reflexive observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimenting) during solving text tasks in Grade 3.

- facilitates the overcoming of re-productivity in the practical activities of the students. As a result of this, education in mathematics is not only reproductive but also flexible learning.

- facilitates the development in the students of a higher level of knowledge, skills, and competencies from competency Cluster Modelling, related to child’sextracting playinformation duringfrom restrictivedifferent measures:sources playlike availability,tables frequencyand drawings, modeling of playsituations behaviors,from playthe real world using mathematical numerical expressions as a means of expression, playwell as asummarizing supportthe ofresults socialreceived cohesion,after play assolving a meansparticular ofproblem.

The with stress, and skill development game. These authors state that itfollowing is preciselygetting thecompletely playdeveloped:

- Students’

encourage coping with stress, expression, sociability,knowledge and skillsdevelopmenttoduringsolveperiodsordinary and composed text tasks with direct and indirect use ofisolationrelations; - Students’

quarantine.ConclusionChildren are a vulnerable group that experience fear, anxiety, uncertainty,knowledge andphysicalskills to compose text tasks by given pictures with numerical data, tables, andsocialnumericalisolationexpressions; - Grade 3 students’ reflexive skills for solving different types of text tasks.

The use of Kolb’s model of experimental learning helps to increase students’ activity during the Coronaeducational crisesprocess in mathematics, form them reflexive skills, and maymake missthem schoollearn by consideration of their experience.

References

Corno, L., & Snow, R. E. (1985). Adapting teaching to individual differences among learners. In M.C. Wittrock, ed., Handbook of research on Teaching, 3rd ed., New York, N.Y.: Macmillan and kindergartenCo., for605–620.

Doncheva, long time. Understanding their reactions and feelings is indispensable to meet their needsJ. (Jiao et al., 2020)2017). WithPrinciples thisof informationtraining in mind,line by using the qualitative research method of focus groups, this research aimed to comprehend children’s perception, experience, emotions, and knowledge relating to coronavirus, restrictive measures, andwith the new way of life that the pandemic requires. At the time of restrictive measures, it is troublesome to enter institutionsthinking and conductaction. researchSEA directly- withConf., very3 youngInternational children,Conference so(p. this74). researchNaval providesAcademy, paramount insight into children’s perceptions of coronavirus and time spent in isolation from friends and kindergarten. In the future, it would be interesting to research a larger sample of children using a mixed methodology. Research of kindergarten children with current experiences and events may not be repeated, so such research must promptly be designed to understand the comprehension, knowledge, and fears of kindergarten children and respond accordingly in the future state of emergencies. Retrospective research of such situations is not so reliable because children may not be able to recall their experiences related to a particular topic of research.Constanta.

Literature

Dunn,

Adler,R., & Dunn K., Salantera,Price, S. i Zumstein-Shaha, M.G. (2019)1982). FocusManual: GroupProductivity Interviewsenvironmental inpreference Child,survey. Youth,Lawrence, andKS: ParentPrice Research: An Integrative Literature Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/1609406919887274.Systems.

Chatterjee,Dunn, S. (2018). Children's Coping, Adaptation and Resilience through Play in Situations of Crisis. Children, Youth and Environments, 28(2)R., 119–145.

Clarke, A. (1999). Focus group interviews in health-care research. Professional Nursing, 14, 395–397.

Dalton, L., Rapa, E. i Stein, A. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30097-3.

Edwards M., Davis H. (1997). The child’s experience. In: Counselling children with chronic medical conditions. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society, 28–48.

Graber,Dunn K., Byrne, E. M., Goodacre, E. J., Kirby, N., Kulkarni, K., O’Farrelly, C. i Ramchandani, P.Price, G. (2020)1985). AManual: rapidLearning reviewstyle inventory. Lawrence, KS: Price Systems.

Felder, R. (1996). Maters of thestyles, impactASEE ofPrism, quarantine and restricted environments on children’s play and health outcomes. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/p6qxt.

Imran N, Zeshan M. i Pervaiz, Z.6 (2020).December Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences1996), 67–72.№ doi:4, 10.12669/pjms.36.

Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M. i Somekh, E. (2020). Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children during the COVID-19 Epidemic.The Journal of Pediatrics. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013.

Kelly, L. (2013). Conducting focus groups with child participants. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, 36, 78–82.

Klein, T. P., Devoe, E. R., Miranda-Julian, C. i Linas, K. (2009). Young children’s responses to September 11th: the New York City experience. Infant Ment Health, 30, 1–22.

Lubit, R., Rovine, D., DIefrancisci, L. i Eth, S. (2003). Impact of Trauma on Children. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 9(2), 128–138. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200303000-00004.

Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva Athanasio, B., Cecília de Sena Oliveira, A. i Simoes Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 101845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

Morgan, M., Gibbs, S., Maxwell, K. i Britten, N. (2002). Hearing children’s voices: methodological issues in conducting focus groups with children aged 7-11 years. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1177/1468794102002001636.

Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delvecchio, E., Mazzeschi, C., & Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Quarantine in Youth From Italy and Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., Letterie, M. i Davis, M. M. (2020). Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics, 146(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824

Petrović-Sočo, B. (1999). Važnost igre. Dijete, vrtić, obitelj: Časopis za odgoj i naobrazbu predškolske djece namijenjen stručnjacima i roditeljima, 4(16), 10–13.

Roccella M. (2019). Neuropsychiatry service of childhood and adolescence - Developmental Psychiatry.

Shaw, C., Brady, L.-M. i Davey, C. (2011). Guidelines for research with children and young people. London: NCB Research Centre National Children’s Bureau.

Sithon, K. (2020). Understanding Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Children about COVID-19. Save the Children International: Cambodia.

Sprang, G., Silman, M. (2013). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(1), 105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22.

Wood, E. (2010). Developing integrated pedagogical approaches to play and learning. In E. Wood, P. Broadhead & J. Howard. Play and learning in the early years (1–9) London: Sage Publications Ltd.

World Health Organization. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak [PDF document].18–23. Retrieved from https:http://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdfncsu.edu/felder-public/Papers/LS-Prism.htm.

WorldFielding, Health Organization.M. (2020)1994). MentalValuing healthdifference in teachers and psychologicallearners: resilienceBuilding duringon Kolb’s learning styles to develop a language of teaching and learning. The Curriculum Journal 5, 395.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. London, UK: Further Education Unit, 20.

Griggs, Sh. (1991). Learning styles counseling. ERIC: Digest, ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services Ann Arbor MI., ERIC Identifier: ED341890, 2.

Healey, M., & Jenkins A. (2000). Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education, Journal of Geography, 99, 185–195.

Ivanov, I. (2004). Stilove na poznanie i uchene. Teorii. Diagnostika. Etnicheski I polovi variaciii v Bulgaria [Styles of knowledge and learning. Theories. Diagnostic. Ethnical and sex variations in Bulgaria]. Shoumen, 30.

Jenkins, A. (1998). Curriculum Design in Geography. Cheltenham, UK: Geography Discipline Network, Cheltenham and Gloucester College of Higher Education.

Keefe, J. W. (1979). Learning style: An overview. In NASSP's Student learning styles: Diagnosing and prescribing programs. (pp. 1–17). Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the COVID-19Source pandemic.of RetrievedLearning fromand https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/mental-health-and-psychological-resilience-during-the-covid-19-pandemic#:~:text=Children%20are%20likely%20to%20be,mental%20well%2DbeingDevelopment. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 38.

Krumova, Al. (2018). Kognitiven stil i stilove na uchene pri uchenicite [Cognitive style and learning styles of students]. Pre-school and school education, No 1.

Lecheva, G. (2009). Stilovete na uchene kato pedagogicheska kompetentnost za raznoobrazyavane na prepodavatelskite strategii [Learning styles as a pedagogy competency for diversification of teaching strategies]. Scientific works of the University of Russe, Volume 48, series 6.2.

Mihova, М. (2002). Prepodavaneto i ucheneto. Teorii. Stilove. Modeli [Teaching and studying. Theories. Styles. Models]. Veliko Tarnovo, 79.

Perrin, J. (1981). Primary version: Learning style inventory. Jamaica, NY: Learning Style Network, St. John's University.

Poya, D. (1972). Kak da se reshava zadacha [How to solve mathematical tasks]. National education.

Riding, R. (1997). On the nature of cognitive styles. Educational psychology, 17, 29–49.

Riding, R., & Chema I. (1991). Cognitive styles: an overview and integration. Educational psychology, 11(3&4), 193–215.

Rogiers, H. (1985). Guide mathematique de base pour l’ecole primaire – geometrie, grandeurs, problems. Bruxelles, 229-234.

Zheleva-Terzieva, D. (2019). Educational Dimensions of Sports and Animation Activity in Educational Environment. Pedagogical Review - Scientific Journal of Educational Issues, Ss. Cyril and Methodius” in Skopje, Faculty of Pedagogy “St. Kliment Ohridski”- Skopje, year 10, issues 2, 21–28.

Zhelyazkova, Zl. (2018). Efektivno uchene na angliyska gramatika [Effective learning of English grammar]. St. Zagora, Trakia University, ISBN: 978-954-314-085-5, 104.

2. Međunarodna znanstvena i umjetnička konferencija Učiteljskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Suvremene teme u odgoju i obrazovanju – STOO2 - in memoriam prof. emer. dr. sc. Milanu Matijeviću, Zagreb, Hrvatska |

Dječje percepcije izvanrednog stanja izazvanog epidemijom COVID-19 |

Sažetak |

|

Za vrijeme koronakrize djeca se mogu suočavati s osjećajima straha, neizvjesnosti te fizičke i društvene izolacije zbog propuštanja škole ili vrtića. Razumijevanje njihovih reakcija i osjećaja ključno je za pravilno zadovoljavanje njihovih potreba (Jiao i sur., 2020). Cilj ovog rada bio je istražiti dječje percepcije izvanrednog stanja izazvanog koronavirusom, a kao metoda korištene su fokus-grupe s djecom od 4 godine do 6 godina. Kvalitativnom analizom sadržaja razvijene su sljedeće kategorije: 1. Znanja o virusu, 2. Znanja o preventivnim mjerama, 3. Komunikacija o virusu, 4. Osjećaji za vrijeme trajanja epidemije, 5. Strategije nošenja s negativnim emocijama za vrijeme trajanja epidemije. U vrijeme restriktivnih mjera teško je ući u ustanove i neposredno provoditi istraživanja s vrlo malom djecom, stoga ovo istraživanje daje važan uvid u dječje percepcije o koronavirusu i vremenu provedenom u izolaciji od prijatelja i vrtića. |

|

Ključne riječi |

|

djeca predškolske dobi, dječje percepcije, epidemija, koronakriza, izolacija |