Razlike među udžbenicima iz Matematike i utjecaj njihovih promjena na odabir i način rada učitelja

Ivana ConarKatolička osnovna škola Svete Uršule, Varaždin |

|

Stručni rad |

Sažetak |

|

Udžbenik je osnovni obrazovni materijal bez obzira nalazi li se on u tiskanom ili digitalnom obliku. Na tržištu su danas prisutni brojni udžbenici različitih izdavačkih kuća a njihov sadržaj mora biti odobren od strane Ministarstva znanosti i obrazovanja prema Zakonu o udžbenicima i drugom obrazovnim materijalima za osnovnu i srednju školu. Učitelji imaju potpunu slobodu odabira udžbenika ovisno o vlastitim afinitetima rada ili pak načina rada njihovog razreda. Od osamostaljenja Republike Hrvatske kroz različite reforme obrazovanja, mijenjali su se udžbenici, njihov sadržaj i struktura te način rada prema njima. Sve se više tražila samostalnost i kreativnost učitelja i učenika a sve je došlo do izražaja 2019. godine kada se u Republici Hrvatskoj počinje provoditi kurikularna reforma „Škola za život“. Tu kulminira promjena sadržaja i strukture udžbenika, digitalizacija udžbenika te samostalno učeničko kreiranje zadataka kao i individualnost učiteljskog procesa kreiranja nastave. S obzirom na dostupnost udžbenika i razlike među njima ispitane su percepcije učitelja primarnog obrazovanja o odabiru udžbenika te primjeni istih u nastavi. Istraživanje je provedeno u jednoj osnovnoj školi među četiri učiteljice razredne nastave. Ujedno nas je zanimalo, koliko se promijenila struktura i sadržaj udžbenika unazad dvadesetak godina pa sve do kurikularne reforme „Škola za život“. Usporedba je provedena među udžbenicima za 4. razred nekoliko izdavačkih kuća. |

|

Ključne riječi |

|

radni udžbenik; individualnost; kurikulum; odgojno-obrazovni ishodi; zadatci |

Introduction Uvod

InDijete Januaryse od svog rođenja susreće s različitim knjigama čiji se sadržaj i struktura mijenja s godinama. Od prvih školskih dana susreće se i s različitim tipovima udžbenika. Za učenike razredne nastave, udžbenik iz Matematike je onaj koji ima najviše zadataka i zahtijeva najviše računanja.

Učenici često doživljavaju matematiku kao teži nastavni predmet i zbog toga pri usvajanju novog gradiva učenici često osjećaju stanovit psihološki pritisak (Rađa, 2020, thestr. World7. Healthprema OrganizationKurnik, (WHO)2009). declaredGledajući thekroz newpovijest, coronavirusmože diseasese (COVID-19)zaključiti outbreakkako ansu emergencyse formatematički internationalzadatci publicrazvijali health.i Thebivali Worldzapisivani Healthod Organizationšpiljskih haszidina, expressedzemljanih concernposuda forpa thesve highdo riskdanašnjih ofdigitalnih thedimenzija. spreadNašim ofprecima COVID-19je inrobna countriesrazmjena aroundbila thejedna world.od Inprvih Marchmatematičkih 2020,zadataka. theS Worldrazvitkom Healthpopulacije Organizationi evaluatedrazvojem thatškolstva, COVID-19matematički cansu bese characterizedzadatci aszapisivali kredom na pločama, zatim se pojavila olovka i bilježnica, a pandemic.potom Thei Worldškolski Healthudžbenici. OrganizationDanas andsu theškolski publicudžbenici healthpopraćeni sectorsi aroundsvojim thedigitalnim worldzadatcima arei involvedneizostavan insu preventingdio thesvakog pandemic.sata However,Matematike.

Prema timeZakonu ofo crisisudžbenicima isi stressfuldrugim forobrazovnim thematerijalima entireza populationosnovnu (WHO,i 2020).srednju Pandemicsškolu are„Udžbenik rare,je butobvezni theyobrazovni canmaterijal devastatingu crisessvim thatpredmetima, canizuzev influencepredmeta thes livespretežno ofodgojnom manykomponentom, childrenkoji andsluži theirkao familiescjelovit physically,izvor socially,za andostvarivanje psychologicallysvih (Sprangodgojno-obrazovnih andishoda Silman,utvrđenih 2013).predmetnim Onekurikulumom, ofkao thei vulnerableočekivanja groups,međupredmetnih whotema hadza topojedini adjustrazred toi thepredmet. pandemicSadržaj swiftly,i arestruktura childrenudžbenika andmora adolescentsomogućavati (Sharma,učenicima Majumder,samostalno andučenje Barman,i 2020).stjecanje Childrenrazličitih arerazina noti indifferentvrsta tokompetencija, thekao dramatici effectvrednovanje ofusvojenosti theodgojno-obrazovnih COVID-19ishoda pandemic.i Theyočekivanja experiencemeđupredmetnih fear,tema. uncertainty,Udžbenik physicalmože andbiti socialtiskani isolation,i/ili and may miss school forelektronički, a longmože time.se Understandingsastojati theirod reactionstiskanog andi emotionselektroničkog isdijela. essentialZnanstveni, topedagoški, accordinglypsihološki, meetdidaktičko-metodički, theiretički, needsjezični, (Jiaolikovno-grafički eti al.,tehnički 2020).zahtjevi Sprangza andizradu Silmanudžbenika, (2013)kao collectedi dataoblik fromudžbenika za pojedini predmet, razred i razinu obrazovanja, predstavljaju udžbenički standard, a sampleutvrđuju ofse 586pravilnikom parentskoji anddonosi theirministar children’snadležan psychosocialza reactions to the pandemic disasters. In data collection, they used a mixed methodology: questionnaires, focus groups, and interviews. The survey results showcased that a large number of parentsobrazovanje.“ (44%)Hrvatski whosabor, had been in quarantine or isolation reported their children as not needing mental health care services, while the rest of the parents (33.4%) reported that their children started to use mental health care services connected to their own experiences during or after the pandemic. The most frequent diagnoses for these children were acute stress disorder (16.7%), adjustment disorder (16.7%), and grief (16.7%)2018).

AnPoljak early(1980) studyu ofsvojoj behavioralknjizi andističe emotionalkako reactionsbi ofpisac Chineseudžbenika childrenmorao:

Prema riječima Poljaka (1980) najbolje bi bilo da su sve kvalitete autora udžbenika objedinjene u jednoj osobi, primjerice od predmetnih nastavnika s dugogodišnjim pedagoškim iskustvom i poznavanje ciljeva reforme školstva, a u koliko to stopnije themoguće, furtherpotrebno spreadje ofangažirati COVID-19,više parentsautora filled– outtandem anili onlinetim questionnairepedagoga abouti theirpredmetnih children’sstručnjaka, behavioralda andpišu emotionalisti responses to the epidemic. The survey results of a sample of 320 children aged 3 to 18 years old showcased excessive parental attachments, distraction, irritability, and fear of asking questions about the epidemic as the most common behavioral and emotional problems. Furthermore, the results demonstrated excessive parental attachment and angst for possible infection of family members as symptoms more likely to develop in kindergarten children aged 3 to 6 years old (Jiao et al., 2020). udžbenik.

AKako studyse conductedrazvijalo onškolstvo au sampleRepublici ofHrvatskoj, 1143razvijali parentssu andse childreni frommatematički 3udžbenici. toGledajući 18razvoj yearsudžbenika ofkroz age,povijest, whichmože analyzedse immediatezaključiti psychologicalkako effectssu ofna COVID-19samom quarantinepočetku, onudžbenici Spanishiz andMatematike Italianbili youth,u showcasedpotpunosti thatili asgotovo manyu aspotpunosti 85.7%neradni, ofodnosno parentsu noticednjima emotionalsu andbile behavioralobjašnjene changesnastavne teme i jedinice bez ili s tek pokojim primjerom (najčešće) riješenog zadatka popraćene radnom bilježnicom ili zbirkom zadataka u kojima su bili zadatci za rješavanje. S vremenom, udžbenik iz Matematike sve je više postajao radnim udžbenikom, odnosno oblikovan na način theirda childrenomogućuje duringupisivanje quarantine.rješenja Theili mostodgovora frequentu symptomsrazrednoj werenastavi concentrationosnovne difficultiesškole.“ (76.6%),Hrvatski boredomsabor, (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), feelings of loneliness (31.3%), and worry (30.1%) (Orgilés, Morales, Delvecchio, Mazzeschi, and Espada, 2020)2018).

InDanas, theiru paper,informatičko Imran,doba Zeshan,digitalizacije, andtiskani Pervaizudžbenici sve su više popraćeni i digitalnom verzijom koja je također propisana zakonom. „Elektronički udžbenik ili elektronički dio udžbenika mora sadržavati barem jednu od sljedećih triju značajki: dinamičko predočavanje, simulaciju (2020)virtualni presentpokus) thei most prevalent symptoms of stress in young children during the pandemic. Young children most often exhibit stress in disapproval and irritability, inability to concentrate, as changes in sleep patterns, in waking up during the night, having nightmares, and in various regressive behaviorsinterakciju (suchna asrelacijama thumbučenik sucking,– notsadržaj, controllingučenik urination,– and/ornastavnik defecation,i/ili andučenik demanding– to be carried)učenik). In conclusion, the authors state that interventions should focus on nurturing resilience in children and adolescents by encouraging structure, routine and physical activity, and better communication to address children’s fears and concerns.

The 2020 study titled How does the COVID-19 pandemic affect the mental health of children and adolescents?, summarized relevant and available data on the mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing 51 topic-related articles. As expected, results determined different responses to stress in a different developmental stages. Yet, children of all developmental stages showcased a higher rate of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptoms, as would be expected after any highly traumatic occurrence“ (MarquesHrvatski desabor, Miranda, da Silva Athanasio, Cecília de Sena Oliveira, and Simoes Silva, 2020)2018).

InStjecanje thematematičkog Unitedznanja States,i kompetencija, djeci je najčešće jedan od najtežih školskih ciljeva pa je uz učitelja koji mora biti sposoban stvoriti okruženje za učenje tako da promiče matematičko razmišljanje i zaključivanje (Sood i Jitendra, 2007 prema Baxter i sur., 2002), upravo udžbenik jedan od najznačajnijih faktora vezan uz uspješnost usvajanja matematičkih kompetencija kod učenika (Sood i Jitendra, 2007). Kako bi se potaknula učenička samostalnost i učiteljska kreativnost u radu, od 2018. godine je u 48 osnovnih i 26 srednjih škola započelo provođenje kurikularne reforme pod nazivom „Škola za život“. Kroz nju, naglasak je na samostalnosti, istraživanju te raznovrsnosti, ali i digitalizaciji sadržaja. Usprkos kreativnosti autora i napretku tehnologije, u udžbenicima i dalje nailazimo na razne vrste zadataka koji ponekad nisu prikladni za određenu nastavnu jedinicu, a nationwidečesto surveyse wasnailazi conductedi inna Junepogrešno 2020.zadane Givenili theriješene pandemic,zadatke.

Različiti surveyoblici aimedzadataka tosu determinejedan changesod innajvažnijih thedijelova physicalsvakoga andudžbenika. emotionalIzbor well-beingzanimljivoga ofi parentsodgovarajućega andzadatka, theirprilagođenoga children.sposobnostima Theučenika resultsdoprinosi showednjihovoj thatmotivaciji 27%koja ofprati parentscjelokupan reportedtijek deteriorationaktivnosti ofučenika theirna mentalputu health,do whilerješenja 14%matematičkoga reported their children’s behavioral problems as worsened. The deteriorated parents’ mental health coincided with children’s worse behavioral problems in nearly one in ten familieszadatka (Patrick,Jurić Henkhaus,i Zickafoose,sur., Lovell,2019, Halvorson,str. Loch,472, Letterie,prema &Heize, Davis, 2020)2005).

QuarantineNa duetržištu toudžbenika COVID-19nalazi hasse hadnekoliko effectsizdavačkih onkuća thekoje livesse ofprilikom mosttiskanja childreni andizdavanja adolescents.udžbenika Theymoraju replacedvoditi friendshipsZakonom ando routinesudžbenicima ofi goingdrugim toobrazovnim kindergartenmaterijalima oru schoolosnovnoj withi virtualsrednjoj socialškoli. meetingsIpak, anddo classes.škola Outdoornajčešće leisuredolaze wasdvije boundili totri thenajveće indoors.izdavačke Closing-downkuće wasi imperativeprezentiraju tosvoje fightudžbenike thekao pandemic,one butnajbolje, the halt on social contact and the ban of going outside can have immediate psychological effects on children and adolescents. There were some public debates about whether the quarantine will affect children or whether they will be able to adjust to the new environment without excessive emotional strain. Knowledge about the effects quarantine has on the psychological welfare of children would aid professionals in implementing preventive measures (Orgilés etnajviše al.,popratnih 2020).materijala i s naviše recenzija učitelja.

TheKroz Worldovaj Healthrad Organizationpokušat ćemo dati kratak pregled samo dijela udžbenika iz Matematike trenutno dostupnih na tržištu udžbenika, odnosno razlike u nekim osnovnim karakteristikama poput godine izdavanja, broja svezaka i stranica, zatim broja nastavnih cjelina, jedinica ili dodataka te broja i tipova zadataka. Pokušat ćemo dati odgovore na pitanja: Kako se promijenila struktura i sadržaj udžbenika iz Matematike unatrag nekoliko godina? Kako promjena udžbenika iz Matematike utječe na odabir i način rada učitelja?

Matematički udžbenik

Nastavna praksa je usko povezana s udžbenicima (WHO,Pansell, 2020)Boistrup, defines the current time as an increased stress-and-crisis time, stating that children are expected to be more demanding and needing more attention from their parents. Moreover, the World Health Organization recommends honest and age-appropriate conversations to ease their children’s anxiety. Overall, the knowledge base on children’s reactions to trauma and disastrous events is expanding, but the descriptions of their reactions during epidemics remain scarce (Klein, Devoe, Miranda-Julian, & Linas, 2009).

Given the previous research on psychosocial, behavioral, and emotional reactions of children during the COVID-19 epidemic – which results, due to the movement-restriction measures implemented to prevent further infection spread of COVID-19, were collected by parents filling out online surveys – this paper aims to research children’s perception on state of emergency caused by the Coronavirus. This research will use focus groups of children aged 4 to 6 years old as the method, bearing in mind the children’s expressed fear of asking questions about the epidemic (Jiao et al., 2020) and the World Health Organization’s advice of honest and age-appropriate conversation to alleviate stress and anxiety (WHO, 2020). Focus groups create2015) a safeoni peerse environmentrazlikuju foro children;veličini, thenaglašenosti methodpojedinih cantema helpiz avoidkurikuluma, somestrukturi poweri imbalances between researchers and participants, such as those between an adult and a child in a one-on-one interview Shaw, Brady, & Davey, 2011). Focus groups not only give researchers a large amount of data on a particular topic in a relatively short time but also encourage discussion and ask participants to explore and clarify their viewssloženosti (Clarke,Foxman 1999). ItMatematički isudžbenik anmože increasinglyse popularopisati researchkao methodslužbeno suitableautorizirana fori collectingpedagoški dataosmišljena frommatematička children,knjiga youngnapisana people,s andciljem parentsda učenicima ponudi matematičke sadržaje. (Adler,Glasnović Salantera,Gracin, and2013, Zumstein-Shah,str. 2019).211.) Thea goalučitelji ofga effective,koriste orkako guided,bi focusrazumjeli groupsciljeve arekurikuluma toi expressoblikovali children’ssvoj voicerad andu point of view on various topicsrazredu (Kelly,Sevilmi, 2013),Çevlik andi soKul, the2022, goalstr.17).Wang ofi theYang paper(2016) isističu tokako examinesu children’smnoga perceptionistraživanja ofusmjerena thena stateusporedbu ofnastavnog emergencyplana causedi byprograma thematematike COVID-19i epidemicudžbenika bymatematike thea self-representationudžbenici ofmatematike participantsmogu usedse insmatrati thei focusnajvažnijim grouppovijesnim researchdokazom method.

Method

razvoj Participantsmatematičkog kurikuluma i cjelokupne povijesti matematičkog obrazovanja te da je upravo udžbenik taj koji nam može pomoći u realizaciji promjena u matematičkom obrazovanju jedne zemlje.

TheGlasnović participantsGracin werei eightDomović children(2009) fromnapravile su zanimljivo istraživanje o upotrebi matematičkih udžbenika u nastavi matematike u višim razredima osnovne škole u Hrvatskoj gdje su utvrdile kako udžbenik ima veliki utjecaj u nastavi te je glavni izvor u pripremi nastavnika za nastavni sat, a kindergartenorganizacija inudžbenika, Osijek-Baranjasadržaji county.i Childrensugerirani participatedmetodički inpostupci utječu na samu organizaciju nastave, njezin sadržaj te metodičke postupke koji se primjenjuju na satu.

Newton i Newton (2007) u svom istraživanju također navode važnost primjenjivosti zadataka u udžbenicima u svakodnevnom životu odnosno da zadatci budu povezani s primjerima iz stvarnog života te prikazani obliku različitih igara.

Analiza odobrenih udžbeničkih komplet riste u Hrvatskoj u školskoj godini 2017./18. je pokazala kako u većini udžbenika četvrtih razreda prevladavaju zadatci koji provjeravaju činjenično znanje, a guidednajmanje groupsu discussion,zastupljeni inzadatci twokoji focuszahtijevaju groupsnajviše onmisaone theprocese 12thiz anddomene 13th of May 2020, which was the first week in which children could return to the kindergarten after all of them closed down in the Republic of Croatia from 16th of March 2020 to 11th of May 2020. The age of the children ranged from 4 years to 6 years, and on average 5 years oldzaključivanja (59Hotovec, months).2018, Threestr. girls and five boys participated in the focus groups. The sample was convenient.

Procedure

The parents of all participants and participants themselves were familiarized with the objectives of the research and the parents gave written consents. Children were informed of the research aims and were asked about understanding what was explained to them, to which they gave informed verbal consent. Children were informed that they could stop participating in the research at any moment. Both focus groups lasted approximately 20 minutes, led by the research protocol in the kindergarten rooms. At the beginning of the discussion, children received puzzles to play with because some researchers noticed that giving children puzzles during discussions made them more relaxed, prompting them to have better and richer answers to the research questions (Morgan, Gibbs, Maxwell, and Britten, 2002).

The research protocol consisted of nine questions. At the beginning of the conversation, children were asked an introductory question: Will you talk to me a bit and solve the puzzle?, and then the transitional question: Do you know why you haven’t been to the kindergarten lately? Key questions followed: What is a virus? How can it harm us? Do you know how we get this virus? Can we do something not to get it? Have you talked to somebody about coronavirus? Are there any places you used to go to, but now you cannot because of the virus? Lastly, the children were asked the final question: Are you interested in anything else about the coronavirus? You can ask me any question if you want65).

ContentMetode analysisprikupljanja results and discussionpodataka

TheOvim contentradom ofnastojalo these audioispitati recordingsmišljenje wasučitelja listenedprimarnog obrazovanja o razlikama među udžbenicima iz Matematike s kojima su dosad radili kao i utjecaj odabira udžbenika na njihov rad. Ispitivanja su provedena tijekom prosinca 2021. godine putem intervjua s učiteljicama primarnog obrazovanja. Za istraživanje su odabrane učiteljice od 1. do 4. razreda u jednoj varaždinskoj osnovnoj školi na način da svaka učiteljica predstavlja jedno razdoblje odnosno po jedan razred u razrednoj nastavi te da se razlikuju prema starosnoj dobi i godinama radnog iskustva. Intervju se sastojao od 17 pitanja podijeljenih u dva dijela, prvi općeniti dio koji se odnosi na općenite podatke o učiteljicama (dob, radno iskustvo, zadovoljstvo udžbenicima u dosadašnjem radu) te drugi dio koji se odnosi udžbenik iz Matematike po kojem učiteljice trenutno rade.

Također, cilj je bio ispitati utjecaj promjena udžbenika na odabir i način rada učitelja. Kako se promijenila struktura i sadržaj udžbenika iz Matematike unatrag nekoliko godina ispitano je na primjeru udžbenika iz Matematike za 4. razred osnovne škole. Matematički su udžbenici međusobno uspoređeni prema osnovnim karakteristikama poput godine izdavanja, broja svezaka i stranica, zatim broja nastavnih cjelina, jedinica ili dodataka te broja i tipova zadataka. Pitanja za intervju te popis analiziranih udžbenika nalazi se u Prilogu.

Rezultati

Kako se promijenila struktura i sadržaj udžbenika iz Matematike unatrag nekoliko godina ispitano je na primjeru udžbenika iz Matematike za 4. razred osnovne škole. Udžbenici su međusobno uspoređivani prema odabranim karakteristikama poput godine izdavanja, broja svezaka i stranica, zatim broja nastavnih cjelina, jedinica ili dodataka te broja i tipova zadataka. S obzirom na velik broj izdavačkih kuća na tržištu, odlučili smo slučajnim odabirom usporediti udžbenika triju najvećih izdavačkih kuća.

Tablica 1.

Usporedba udžbenika Matematike prema izdavačkoj kući, godini izdanja, broju svezaka i stranica.

|

Naslov udžbenika |

Izdavačka kuća |

Godina izdanja |

Broj svezaka |

Broj stranica |

|

Matematika 4 |

Alfa |

2000. |

1 |

72 |

|

Matematika 4 |

Školska knjiga |

2002. |

1 |

94 |

|

Matematika 4 |

Alfa |

2016. |

1 |

100 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

Školska knjiga |

2018. |

1 |

143 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

Školska knjiga |

2019. |

1 |

140 |

|

Matematička mreža 4 |

Školska knjiga |

2021. |

1 |

126 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

Školska knjiga |

2021. |

1 |

141 |

|

Otkrivamo matematiku 4 |

Alfa |

2021. |

2 |

(127+125) 252 |

|

Nino i Tina 4 |

Profil |

2021. |

2 |

(124+128) 313 |

|

Super matematika za prave tragače |

Profil |

2021. |

2 |

(161+152)282 |

Prema uspoređivanim naslovima (Tablica 1), možemo zaključiti kako Školska knjiga matematički udžbenik najčešće ima u jednom svesku, dok su izdavačke kuće Alfa i Profil najčešće u dva sveska. Novija izdanja iz 2021. godine izdavačke kuće Alfa i Profil sva izdanja imaju u dva sveska (radni udžbenik bez posebno izdvojene radne bilježnice), dok Školska knjiga još uvijek ima jedan svezak (posebno radnu bilježnicu). Iz podataka je vidljivo kako se broj stranica radnih udžbenika povećao s godinama. Prije dvadesetak godina, radni su udžbenici imali manje od sto stranica, dok najnovija izdanja imaju i preko tristo stranica (najčešće dvjestotinjak). Također, starija su izdanja uz udžbenik imala popratno i radnu bilježnicu, dok su novija izdanja uglavnom radni udžbenici s integriranom radnom bilježnicom. Izdavačka kuća Alfa je u svojem izdanju Matematika 4 iz 2000. godine koje ima 72 stranice, povećala na 200 stranica koliko ima izdanje iz 2021. godine. Izdavačka kuća Školska knjiga 2002. godine u svom udžbeniku Matematika 4 ima 94 stranice, dok udžbenik Matematička mreža 4 iz 2021. godine ima 126 stranica, a Moj sretni broj 4 iz 2021. godine ima 141 stranicu.

Tablica 2.

Usporedba udžbenika prema broju nastavnih cjelina i jedinica.

|

Naslov udžbenika |

Nastavne cjeline |

Nastavne jedinice |

Dodaci |

|

Matematika 4 |

13 |

52 |

0 |

|

Matematika 4 |

0 |

50 |

1 |

|

Matematika 4 |

12 |

65 |

1 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

7 |

58 |

1 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

7 |

58 |

1 |

|

Matematička mreža 4 |

0 |

42 |

2 |

|

Moj sretni broj 4 |

8 |

50 |

1 |

|

Otkrivamo matematiku 4 |

9 (4+5) |

65 (35+30) |

2 |

|

Nino i Tina 4 |

8 (4+4) |

56 (29+27) |

1 |

|

Super matematika za prave tragače |

7 (4+3) |

53 (28+25) |

2 |

Iz Tablice 2 je vidljivo kako uspoređivani udžbenici Školske knjige nemaju sadržaj podijeljen na cjeline već samo na jedinice dok ostale izdavačke kuće imaju jasno podijeljen sadržaj na cjeline i jedinice. Također, sva novija izdanja, izdana od 2016. godine imaju dodatke na kraju udžbenika (ishode ili njihova objašnjenja kao i kratki pregled cjelokupnog gradiva).

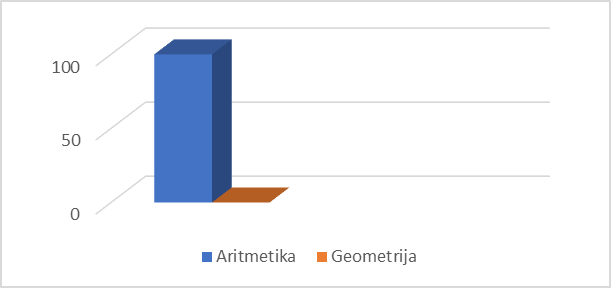

Grafikon 1. Prva cjelina u udžbenicima

Kako je vidljivo u Grafikonu 1, svi udžbenici, bez obzira na izdavačke kuće, kreću s aritmetičkim dijelom gradiva.

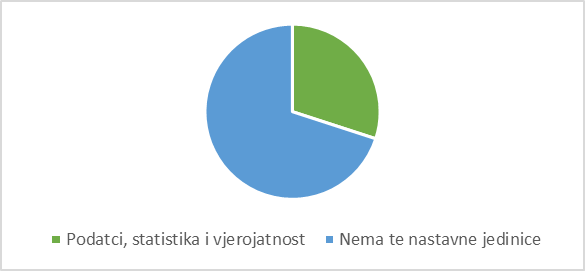

Grafikon 2. Jedinice Podatci i Vjerojatnost u udžbeniku

Nastavna jedinica Podatci, statistika i vjerojatnost je nova jedinica koja se pojavljuje u matematičkim udžbenicima. Iz Grafikona 2 je vidljivo kako se nastavne jedinice Podatci, statistika i vjerojatnost pojavljuje u 30% uspoređivanih udžbenika i to andsu transcribedsve usingudžbenici theizdani computer2021. programgodine, Nvivo.dakle Qualitativeprema content analysis inductively developed the following categories: 1.kurikulumima KnowledgeŠkole ofza the virus, 2. Knowledge of the preventive measures, 3. Communication about the virus, 4. Emotions during the epidemic, 5. Strategies for dealing with negative emotions during the epidemicživot. TheStarija tableizdanja showsudžbenika annigdje examplene ofspominju datanavedene organization,nastavne andjedinicu injer thisnije wayniti ofbila datazastupljena analysis,u thetadašnjem conversationsNastavnom ofplanu thei focus groups are concise and structured for a more easy interpretation.programu.

ResultsTablica 3.

ExampleZadatci ofu datanastavnoj organizationjedinici Pisano množenje višeznamenkastog broja jednoznamenkastim brojem

|

Naslov udžbenika |

Numerički zadatci |

Tekstualni zadatci |

Ostali zadatci (grafički prikazi ilustracije, riješeni primjeri) |

|

Matematika 4 Matematika 4 Matematika 4 Moj sretni broj 4 Moj sretni broj 4 Matematička mreža 4 Moj sretni broj 4 Otkrivamo matematiku 4 Nino i Tina 4 Super matematika za prave tragače |

3 3 3 3 3 3 |

3 1 2 3 3 1 |

2 3 1 1 1 1 |

|

Nema nastavne jedinice pisanog množenja višeznamenkastog broja jednoznamenkastim brojem. |

|||

|

4 3 2 |

1 9 2 |

1 1 1 |

|

Nastavna jedinica Pisano množenje, odabrana je jer zajednička je svim uspoređivanim udžbenicima. Iz podataka u Tablici 3, vidljivo kako u obradi te nastavne jedinice podjednako prevladavaju numerički i tekstualni zadatci. Jedan od udžbenika izdavačke kuće Školska knjiga nema nastavnu jedinicu množenja višeznamenkastoga broja jednoznamenkastim brojem. Dva udžbenika izdavačke kuće Profila imaju više tekstualnih nego numeričkih zadataka.

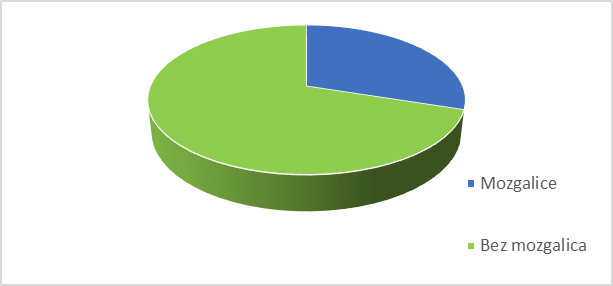

Grafikon 3. Mozgalice na kraju svake nastavne cjeline.

Iz Grafikona 3 je vidljivo kako samo 30% uspoređivanih udžbenika na kraju nastavnih cjelina imaju mozgalice – zagonetke zasnovane na matematičkim pravilima (Borković i Capan, 2019, str. 50) ili zadatke za samoprocjenu. Sadržaj i struktura udžbenika jedan je od bitnih čimbenika prilikom odabira udžbenika za rad u nastavi.

Rezultati intervjua

Kako bismo pokušali odgovoriti što sve utječe na odabir udžbenika kod učitelja, na temelju intervjua s učiteljicama koje rade u razrednoj nastavi jedne osnovne škole, ispitano je kako promjene u strukturi i sadržaju udžbenika iz Matematike utječu na rad učitelja u razrednoj nastavi. Istraživanje je provedeno među četiri učiteljice jedne varaždinske osnovne škole tijekom prosinca 2021. godine. Učiteljice su odabrane slučajnim odabirom.

Tablica 4.

Tablični prikaz podataka o učiteljicama

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Iz Tablice 4. vidljivo je kako učiteljice rade u razrednoj nastavi, svaka predstavlja po jednu generaciju učenika, odnosno od 1. do 4. razreda. Dvije učiteljice su diplomirane učiteljice i imaju više od 10 godina iskustva rada u osnovnoj školi, dok su dvije učiteljice magistre primarnog obrazovanja s manje od 10 godina iskustva rada u školi a sve rade po udžbeniku izdavačke kuće Alfa, Otkrivamo matematiku.

Sve su učiteljice zadovoljne ponudom udžbenika odnosno smatraju da ponuda ide u dobrom smjeru. Također, sve su učiteljice zadovoljne odabranim udžbenikom odnosno načinom na koji je on koncipiran bez obzira o kojem se razredu radilo. Jedna od učiteljica se osvrnula na važnost točnosti zadataka prilikom odabira udžbenika odnosno važnosti recenzenata i povjerenstava koje odlučuju o odobravanju udžbenika prilikom uočavanja pogrešaka koje se javljaju u pojedinim udžbenicima.

Uglavnom sve učiteljice, bez obzira na radno iskustvo primjećuju promjene u sadržaju i strukturi udžbenika od početka njihovog radnog vijeka dosad. Dvije su učiteljice uočile promjene nakon donošenja Kurikuluma za predmet Matematiku odnosno nakon početka provođenja reforme Škole za život. Primjećuju više problemskih zadataka, zadataka riječima, istraživanja, tabličnih prikaza kao i okvira za samoprocjenu učenika kojih prije nije bilo.

Učiteljice su se uglavnom složile kako ne postoji velika razlika u redoslijedu sadržaja, tema, nastavnih jedinica udžbenika s obzirom na izdavače. Učiteljica u prvom razredu smatra kako je možda geometrija negdje u prvom polugodištu, negdje u drugom, negdje na početku, negdje na kraju, ali da uglavnom nema prevelike razlike jer su svi nekako išli od onoga što je djeci bliže prema sadržaju koji još nisu radili. Učiteljica u četvrtom razredu smatra kako se razlikuje redoslijed sadržaja u udžbenicima s obzirom na izdavače. Ona je uspoređivala udžbenik koji trenutno koristi od Alfe s udžbenicima iz Školske knjige čiji je slijed sadržaja u potpunosti drugačiji od ovoga kojeg koristi. Udžbenik izdavačke kuće Alfa bio joj je prihvatljiviji zato što sadrži više mogućnosti za usvajanje Zbrajanja i oduzimanja brojeva do milijun, odnosno dužeg perioda za usvajanje sadržaja geometrijskog dijela. Tu je primijetila neku razliku jer je u Školskoj knjizi kratko ponavljanje sadržaja trećeg razreda. U tim udžbenicima odmah kreću s učenjem novog gradiva, dok u udžbenicima izdavačke kuće Alfa, ima mogućnost više ponoviti, odnosno ustanoviti gdje je koji problem kao i primjerice razraditi tehniku korištenja geometrijskog pribora.

Učiteljica koja radi u drugom razredu smatra da ako se uspoređuju različite izdavačke kuće, nema prevelikih razlika. „Što se tiče, recimo nastavnih jedinica, Alfini udžbenici imaju u prvom polugodištu Zbrajanje i oduzimanje do 100, u drugom polugodištu Množenje i dijeljenje. To je vjerojatno isto u manje-više svim udžbenicima. Razlika je u nastavnim jedinicama Kune i lipe; Računanje s mjernim jedinicama za duljinu i vrijeme. Neke su izdavačke kuće to su stavile na početku, neke na kraju prvog polugodišta, neke na kraju drugog polugodišta“, istaknula je učiteljica. Također, učiteljica je istaknula „kako pojedine nastavne jedinice, recimo Lijeva i desna strana jednakosti, u drugom razredu u Alfinoj izdavačkoj kući je izdvojena posebno. U drugim izdavačkim kućama poput Školske knjige ili Profil, uopće nemaju izdvojeno posebno kao posebnu tu nastavnu jedinicu“.

Učiteljice su istaknule kako o odabiru udžbeniku iz Matematike odlučuju prema preglednosti, sistematičnosti, postupnosti obradi sadržaja i jako im je važno da su različite vrste zadataka. Važno je da cijelo vrijeme nije jedan tip zadataka nego da se kroz različite nastavne jedinice protežu i različiti zadatci. Isto tako da i njihova težina raste od jednostavnijih ka složenijima. Bitno je i da ima više prostora za ponavljanje, za usvajanje nekog novog nastavnog sadržaja što je prilagođeno njihovoj dobi. Važna im je cijela struktura nastavnih sadržaja, nastavnih metoda te slikovni prikaz udžbenika odnosno da grafički bude zanimljiv učenicima. Važno je i da ilustracije budu primjerene, odnosno da pomažu učeniku u shvaćanju zadataka ili nekog pojma, a ne da budu ilustracije tek toliko stavljene u udžbenik, kao i dostupnost ostalih popratnih materijala uz udžbenik poput zbirke zadataka, nastavnih listića, Mozabooka, e-Sfere....

Iako su učiteljice odabrane slučajnim odabirom, rezultati su pokazali kako sve učiteljice koriste udžbenike izdavačke kuće Alfa, Otkrivamo matematiku, izdane 2021. godine. S obzirom na razred u kojem predaju, učiteljice su se složile da trenutno ne bi izbacile nikakve teme. Dodale bi više zadataka za ponavljanje, tabela za učeničke samoprocjene, matematičke igre, mogućnost pisanja diktata ili proširivanja odnosno produbljivanja određenih tema i više sati za određene nastavne jedinice.

U udžbeniku iz Matematike po kojem trenutno rade, sviđaju im se grafičke ilustracije i što svaka tema odnosno jedinica ima neku matematičku priču. Učiteljice ističu kako je sve potkrijepljeno i medijskim sadržajima odnosno: „Ima puno igara“., „Udžbenik prati i digitalni udžbenik, odnosno udžbenički komplet“., „Tamo ima jako puno sadržaja dodatnih kojim se može obogatiti nastavu“., „Ima jako puno materijala koji se može iskoristiti i za dodatnu i za dopunsku nastavu Matematike“. Učiteljice smatraju kako ima bogatstvo sadržaja, a učitelj onda bira ono što je najbolje za njegov rad. Sviđaju im se i ilustracije pa oni učenici koji su više vizualni tipovi mogu povezati sve sa slikom i predavanjem razrednice. Sviđa mi se sustavnost, postupnost, zornost i jasnoća.

U obradi pojedine nastavne teme u udžbeniku iz Matematike nedostaje im pokoji veći zadatak više za razmišljanje, neki problemski zadatak kao dobar uvod. „Nekakve konkretne ilustracije kojom će učenikovo znanje dobiti na kakvoći, na trajnoj uporabi znanja“. „Ponekad su možda ilustracije nepovezane, nisu možda autentične povezane sa stvarnim događajem, a trebalo bi sam sadržaj i tekstualne zadatke povezati drugim predmetima da postoji nekakav suodnos jer su ovakvi neki dijelovi zadataka dosta izmišljeni, apstraktni učenicima“, ističu učiteljice.

Što se tiče satova ponavljanja pojedine nastavne teme u udžbeniku iz Matematike, učiteljice su se uglavnom složile da im ne nedostaje ništa. Naime, imaju i zbirku zadataka tako da ima dovoljno zadataka i za ponavljanje i za vježbanje. Ipak, složile su se da bi bilo dobro više zadataka riječima, problemskih zadataka, mozgalice, različitih tipova igara kroz koju naprednija djeca ili djeca koja brže računaju ili im ide bolje matematika mogu ipak sudjelovati u nastavi u uvježbavanju pa im ne bi bilo „dosadno“.

S obzirom na mikroartikulaciju nastavnog sata u udžbeniku po kojem trenutno rade, gotovo su se sve učiteljice složile da im nedostaju elementi za pojedinu etapu sata, poput zadataka za ponavljanje u uvodnom djelu. Nedostaju im više zadatci za razmišljanje, za logičko razvijanje kao što su matematičke mozgalice, neke primjere za radove u skupinama, u paru gdje učenici imaju veću međusobnu suradnju pa mogu i na taj način utjecati jedni na druge. Samo se učiteljica koja predaje u prvom razredu izjasnila da ima puno sadržaja pa joj često nedostaje vremena jer bi voljela još neke stvari napraviti, provježbati, poigrati se, a jednostavno ne stigne.

Učiteljice smatraju da se u udžbenicima ponekad javljaju nekakvi dvosmisleni zadatci koji iziskuju dodatan angažman učitelja pa je potrebno poraditi na preciznosti u formiranju pojedinih zadataka jer to dosta zbunjuje učenike. Što se tiče potrebe dodavanja određene vrste zadataka, učiteljice su podijeljenog razmišljanja. Dvije od četiri ispitane učiteljice smatraju kako je potrebno dodati mozgalice, različite zadatke riječima, problemske zadatke u kojima bi djeca zapravo razvijala svoje vještine računanja i logike te iza svake nastavne jedinice, neku novu zanimljivu djeci igru, dostupnu u udžbeniku da mogu proći. Druge dvije učiteljice smatraju kako nije potrebno ništa previše dodavati ili izbacivati jer misle da se uvijek može samo još kvalitetno nadopuniti s nekim primjerima zadataka za rad u grupi i više sadržaja za samoponavljanje.

KnowledgeZaključak

Bez obzira na reforme u školstvu i napredak tehnologije, tiskani udžbenik bio je i ostat će temeljni dio sata Matematike kao najvažniji izvor u rješavanju matematičkih zadataka i stjecanju matematičkih kompetencija.

Učitelji i učiteljice koji se svakodnevno u radu susreću s udžbenicima, najbolje znaju koje zadatke i na koji način treba naglasiti. Bilo bi dobro među učiteljima i učenicima, jednom godišnje provesti evaluaciju udžbenika, odnosno sadržaja i zadataka, primjerice koja vrsta zadataka i koji način rada je većini učenika najzanimljiviji. Na taj bi se način prikupile važne informacije te bi se smanjile ako ne i u potpunosti izbjegle pogreške u udžbenicima, poboljšali zadatci u njima, a samim time i poboljšali učenički rezultati matematičkog znanja koje se učitelji, svakodnevno trude produbljivati. Iako rađeni na malenom broju uzoraka, nalazi ovog istraživanja su važni jer upućuju na pozitivno mišljenje učiteljica o većoj kvaliteti zadataka novijih udžbenika iz matematike u odnosu na udžbenike ranijih generacija. Ukupno gledajući, zadovoljne su strukturom i sadržajem te ponudom matematičkih udžbenika za osnovnu školu. Prema stavovima učiteljica možemo zaključiti kako su se dogodile pozitivne promjene u udžbenicima iz Matematike unazad nekoliko godina. Usprkos promjenama, njihov način rada nije se uvelike promijenioer je udžbenik samo jedan od čimbenika ostvarivanja kvalitetne nastave, naglašavajući pritom važnost učitelja u prezentiranju nastavnih jedinica. Najvažnije im je da zadatci budu raznovrsni i prilagođeni za sve učenike bez obzira na razinu znanja, da prate sistematičnost i postupnost te da bude puno više matematičkih igrica i mozgalica, više zadataka za ponavljanje, tablica za učeničke samoprocjene, mogućnost pisanja diktata ili proširivanja odnosno produbljivanja određenih nastavnih tema i veći broj zadataka za određene nastavne jedinice.

Na kraju možemo zaključiti kako bi svim sudionicima odgojno-obrazovnog procesa najvažnija trebala biti sreća, zadovoljstvo i napredak učenika, a upravo se to može postići međusobnom suradnjom, „osluškivanjem“ potreba učenika i učitelja te prednosti i nedostataka školskih udžbenika i sadržaja u njima.

Literatura

Borković, T. i Capan, A. (2019). Mozgalice i zagonetke u nastavi matematike (ili kako pobjeći od izvanzemaljaca koristeći matematiku). Poučak, 20(77), 49–62

Foxman, D. (1999). Mathematics textbooks across the world: some evidence from the third international mathematics and science study. Berkshire: NFER

Glasnović Gracin, D. (2013). Matematički udžbenik kao predmet istraživanja. Croatian journal of education. 16(3), 211–237.

Glasnović Gracin, D. i Domović, V. (2009). Upotreba matematičkih udžbenika u nastavi viših razreda osnovne škole. Odgojne znanosti, 11(2), 45–65.

Hotovec, J. (2018). Analiza zadataka iz matematičkih udžbenika prema zahtjevima TIMSS istraživanja. (Diplomski rad). Zagreb: UFZG. Dostupno na https://repozitorij.ufzg.unizg.hr/en/islandora/object/ufzg:896 [9.2.2021.]

Hrvatski sabor (2018) Zakon o udžbenicima i drugim obrazovnim materijalima za osnovnu i srednju školu NN 116/2018. Dostupno na https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2018_12_116_2288.html

Jurić, J., Mišurac, I. i Vežić, I. (2019). Struktura zadataka prema Bloomovoj taksonomiji u udžbenicima iz matematike za razrednu nastavu. Školski vjesnik: časopis za pedagogijsku teoriju i praksu. 68(2), 469–487.

Ministarstvo znanosti i obrazovanja (2019) Odluka o donošenju kurikuluma za nastavni predmet Matematike za osnovne škole i gimnazije u Republici Hrvatskoj NN 7/2019 Dostupno na https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2019_01_7_146.html

Ministarstvo znanosti, obrazovanja i športa (2006) Nastavni plan i program za osnovnu školu, NN 102/2006 Dostupno na https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2006_09_102_2319.html

Newton, D.P. i Newton, L.D. (2007). Could Elementary Mathematics Textbooks Help Give Attention to Reasons in the Classroom? Educational Studies in Mathematics, 64, 69–84.

Pansell, A., i Bjorklund Boistrup, L. (2018). Mathematics Teachers’ Teaching Practices in Relation to Textbooks: Exploring Praxeologies. The Mathematics Enthusiast, 15, 540–562.

Poljak, V. (1980). Didaktičko oblikovanje udžbenika i priručnika. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Rađa, P. (2020). Struktura zadataka u udžbenicima matematike za razrednu nastavu. (Diplomski rad). Split: Sveučilište u Splitu, Filozofski fakultet.

Sevimli, E., Çelik, S. i Kul, Ü. (2022). Comparison of the COVID-19 virus

A telephone survey, conducted from April to May 2020 on a sample of 241 children aged 10 to 17 years old, obtained the following results. All of the children did know about coronavirus, but only half (57%) knew that it was a virus that can cause serious illness. This raised concern given the fact that COVID-19 is a highly infectious virus. The survey results were surprising because they showcased that children of rural areas (61%) knew more about the virus than the children of urban areas (53%) (Sithon, 2020).

In this study, all eight children were familiar with coronavirus – they knew that they did not go to the kindergarten due to its outbreak and showed knowledge that the virus is in the whole world: It’s a disease in the city…in all cities. Additionally, as it was noted in the aforementioned research in which the children perceived the virus as dangerous (85%), this research as well reported children perceiving the virus as highly dangerous: I could get infected, be sick, and go to the hospital. Furthermore, children knew that the virus is infectious to both children and adults, and some even mentioned pets.

Researcher: Tell me, can this virus infect children?

Girl: Yes, kitties too.

Researcher: What do you think, for whom the virus is the most dangerous?

Girl: For a little baby.

Researcher: Do you think that it is more dangerous for a little baby or grandmas and grandpas?

Boy: For grandmas and grandpas.

Knowledge of the preventive measures

In this study, children listed several preventive measures. For instance, they listed staying at home, that is, minimizing the risk of infection: We have to protect ourselves, be at home. Apart from not being exposed to the virus, children noted hygiene habits and disinfectants: That we are at home, and I have disinfectants in the car and at the bed.; We have to wash our hands.

In research from Cambodia (2020), the majority of the children (99.2%) listed hand-washing and then mask-wearing (80.1%) as a preventive measure (Sithon, 2020). In this research, no child listed mask-wearing as a preventive measure against coronavirus, however, according to the recommendations of the Croatian Institute of Public Health, children from kindergarten children after the second year to early-school years are not obligated to wear masks. Appropriately, these children do not even perceive them as a preventive measure.

Communication about the COVID-19 virus

Communication with kindergarten children about the infections spread and the explanation of the disease should not only include the simplification of language and concepts but should also take into account children’s understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and diseases. From 4 to 7 years of age, children’s comprehension is under the influence of magical thinking, characterized by a child’s belief that thoughts, wishes, and unrelated actions can cause certain events. For example, a child can believe that specific thoughts or behavior can cause illness. Adults have to be aware of children’s developmental stages and be careful in explaining diseases so children would not unjustly blame themselves or feel as if the disease is a punishment for their misbehavior (Edwards and Davis, 1997). Thus, listening to children’s perceptions and beliefs about COVID-19 is crucial to provide them an accurate explanation that they can understand without unnecessarily feeling guilty or scared (Dalton, Rapa, and Stein, 2020). In this research, and regarding communication and information about coronavirus, children state their conversations with primary caretakers, relatives, and kindergarten teachers: I talked a little with mom and dad, they say you shouldn’t go out for the corona.; Yes (I talked), with mom, dad, grandma, and grandpa .; Kristina (kindergarten teacher) talked about it. In a study by Sithon (2020), the majority of the children reported social media and news as primary sources of coronavirus information, while fewer children reported their families. Given the age of these research participants, it is logical to assume communication with caretakers and family as a primary source of information because they are not yet able and not being age-appropriate for them to collect information from news or social media.

Emotions during quarantine

Long periods of quarantine can cause an increase in anxiety, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, isolation, and insomnia in children (Roccella, 2019). Children are vulnerable to the emotional effects of traumatic events, especially those that result in the closing of schools, social distancing, and house quarantines (Lubit, Defrancisci, and Eth, 2003). From statements of children in this study, it is evident that children articulated their emotions regarding the restrictive measures: I was sad because I couldn’t go outside.; I was sad because I didn’t go to kindergarten but I didn’t cry. Time of COVID-19 pandemic is a very unusual time for humanity, but especially for children that had to face huge life changes during the Corona crises. In the line of preventive measures, schools and kindergartens were closed down, which deprived children of a sense of structure, routine, incentives provided by educational institutions, and the feeling of social support from peers, educators, and school teachers. It is very likely that in this time, children will feel concerns, anxiety, and fear, i.e. types of fear often felt by adults, which include fear of death, fear of relatives dying, and fear of receiving medical help. As stated on the World Health Organization’s website (WHO, 2020), all of this contributes to the potential threat to mental health and children’s psychological resilience during the pandemic. These exact fears were felt by children in this research, as it is evident in a statement of a four-year-old boy: I missed my grandparents because I didn't go to them because I was afraid I would infect them if they didn't die. This sentence showcases that extremely young children felt fear of infection and death while experiencing the new normal in which they missed their loved ones whom they otherwise often saw. In addition to the fear of death, it could be observed that the children are worried about stopping the virus and that they are aware that the time of Corona crises could last.

Researcher: Do you think coronavirus is gone, and won’t come back?

Boy 1: But, they said that it will, during fall.

Girl 1: No, during winter

Girl 2: It passed a little.

Researcher: It passed a little, but it’ll come back?

Boy 1: Yes, but during winter, it won’t come back during summer. I guess Corona will go all the time now.

Boy 2: It will never pass.

Strategies for dealing with negative emotions during the epidemic

From the statements of the children in this research, it is noticed that they listed playtime as leisure time during quarantine: I was bored, so I played. Naturally, this is not surprising, given that in play children test various states, moods, and emotions. Play is seen as a form of "emotional hyperventilation." In the play, through "emotional hyperventilation," children play with feelings of fear, anxiety, and abandonment (Wood, 2010). Play is exceptionally important in a life of a child because it is more than just fun. It is a valuable part of the intellectual, social, and emotional development of the child (Petrović-Sočo, 1999), and so in times of crisis, play can help children deal with stress, anxiety, and crisis-related trauma (Chatterjee, 2018).

Graber et al. (2020) reviewed the works related to the effect of the quarantine and restrictive measures on child’s play and health well-being. They identified the following topics that relate to child’s play during restrictive measures: play availability, frequency of playmathematics behaviors,teachers’ play as a meansuse of expression,mathematics playtextbooks asin aface-to-face supportand distance education. Turkish Journal of socialEducation, cohesion,11(1), play as a means of coping with stress, and skill development game. These authors state that it is precisely the play that could encourage coping with stress, expression, sociability, and skills development during periods of isolation or quarantine.16–35.

Conclusion

Children are a vulnerable group that experience fear, anxiety, uncertainty, and physical and social isolation during the Corona crises and may miss school and kindergarten for a long time. Understanding their reactions and feelings is indispensable to meet their needs (Jiao et al., 2020). With this information in mind, by using the qualitative research method of focus groups, this research aimed to comprehend children’s perception, experience, emotions, and knowledge relating to coronavirus, restrictive measures, and the new way of life that the pandemic requires. At the time of restrictive measures, it is troublesome to enter institutions and conduct research directly with very young children, so this research provides paramount insight into children’s perceptions of coronavirus and time spent in isolation from friends and kindergarten. In the future, it would be interesting to research a larger sample of children using a mixed methodology. Research of kindergarten children with current experiences and events may not be repeated, so such research must promptly be designed to understand the comprehension, knowledge, and fears of kindergarten children and respond accordingly in the future state of emergencies. Retrospective research of such situations is not so reliable because children may not be able to recall their experiences related to a particular topic of research.

Literature

Adler, K., Salantera,Sood, S. i Zumstein-Shaha, M. (2019). Focus Group Interviews in Child, Youth, and Parent Research: An Integrative Literature Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/1609406919887274.

Chatterjee, S. (2018). Children's Coping, Adaptation and Resilience through Play in Situations of Crisis. Children, Youth and Environments, 28(2), 119–145.

Clarke,Jitendra, A. (1999). Focus group interviews in health-care research. Professional Nursing, 14, 395–397.

Dalton, L., Rapa, E. i Stein, A.K. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30097-3.

Edwards M., Davis H. (1997). The child’s experience. In: Counselling children with chronic medical conditions. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society, 28–48.

Graber, K., Byrne, E. M., Goodacre, E. J., Kirby, N., Kulkarni, K., O’Farrelly, C. i Ramchandani, P. G. (2020)2007). A rapidComparative reviewAnalysis of theNumber impactSense ofInstruction quarantinein Reform-Based and restrictedTraditional environmentsMathematics onTextbooks. children’s play and health outcomes. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/p6qxt.

Imran N, Zeshan M. i Pervaiz, Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 Pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 67–72. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.

Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M. i Somekh, E. (2020). Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children during the COVID-19 Epidemic.The Journal of Pediatrics.Special doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013.

Kelly, L. (2013). Conducting focus groups with child participants. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, 36, 78–82.

Klein, T. P., Devoe, E. R., Miranda-Julian, C. i Linas, K. (2009). Young children’s responses to September 11th: the New York City experience. Infant Ment HealthEducation, 3041(3), 1–22.145–157.

Lubit,Wang, R., Rovine, D., DIefrancisci, T.L. i Eth,Yang, S.D.C. (2003)2016). ImpactA Comparative Study of TraumaGeometry onin ChildrenElementary School Mathematics Textbooks from Five Countries, .European Journal of PsychiatricSTEM Practice, 9Education(2), 128–1381:3 (2016), 58.

Prilozi

. Prilog doi:1. 10.1097/00131746-200303000-00004.Intervju

- Koliko imate godina?

- Koliko godina radite u školi?

- U kojem razredu trenutno predajete?

- Kako ste zadovoljni ponudom udžbenika iz Matematike?

- Koliko ste i zašto zadovoljni odabranim udžbenikom?

- Koliko se promijenio sadržaj i struktura udžbenika kroz Vaš radni vijek?

- Koliko i na koji se način promijenio Vaš način rad na satovima Matematike s obzirom na promjene u udžbenicima?

- Postoji li velika razlika u redoslijedu sadržaja, tema, nastavnih jedinica udžbenika s obzirom na izdavače?

- Što Vam je presudno u udžbeniku iz Matematike odnosno prema čemu odlučujete koji ćete udžbenik odabrati za rad?

Ovaj dio pitanja odnosi se na udžbenik iz Matematike po kojem učiteljice trenutno rade.

- Koji udžbenik trenutno koristite u nastavi?

- Koje temeiste dodali ili izbacili iz udžbenika iz Matematike za razred u kojem trenutno predajete?

- Koji sadržaji Vam se sviđaju u udžbeniku iz Matematike?

- Što Vam nedostaje u obradi pojedine nastavne teme u udžbeniku iz Matematike?

- Što Vam nedostaje u ponavljanju pojedine nastavne teme u udžbeniku iz Matematike?

- Što biste dodali ili izbacili u udžbeniku iz Matematike? Zašto?

Prilog 2. Popis udžbenika

Marques de Miranda, D.Cindrić, da Silva Athanasio, B.M., Cecília de Sena Oliveira,Dragičević, A. i SimoesPastuović, Silva, A. C.B. (2020)2021). HowMatematička ismreža COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction4, 101845.udžbenik doi:za 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Morgan, M.Ćurić, Gibbs, S., Maxwell, K.F. i Britten,Markovac, N.J. (2000). Matematika 4, udžbenik za četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Alfa.

Đurović, J. i Đurović, I. (2002). HearingMatematika children’s voices: methodological issues in conducting focus groups with children aged 7-11 years. Qualitative Research, 24(1), 5–20.udžbenik doi:za 10.1177/1468794102002001636.četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Orgilés,Glasnović Gracin, D., Žokalj, G. i Soucie, T. (2021). Otkrivamo matematiku 4, udžbenik za četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Alfa.

Jakovljević Rogić, S. i Miklec Prtajin, G. (2021). Moj sretni broj 4, udžbenik za četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Lončar, L., Pešut, R., Rossi, Ž. i Križman Roškar, L. (2021). Nina i Tino 4, udžbenik matematike za četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Znanje.

Markovac, J. (2016). Matematika 4, udžbenik za četvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Alfa.

Martić, M., Morales, A.Ivančić, Delvecchio, E.G., Mazzeschi,Dunatov, C.J., &Brničević Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Quarantine in Youth From Italy and Spain. Frontiers in PsychologyStanić, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579038

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., Letterie, M. i Davis,Martinić M.Cezar, M.J. (2020)2021). Well-beingSuper ofmatematika Parentsza andprave Childrentragače During4, theradni COVID-19udžbenik Pandemic:za Ačetvrti Nationalrazred Survey.osnovne Pediatrics,škole, 146(4).Zagreb: doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824 Profil.

Petrović-Sočo,Miklec, B.D., Jakovljević Rogić, Prtajin, G., Binder, S., Mesaroš Grgurić, N. i Vejić, J. (1999)2018). VažnostMoj igre.sretni Dijete,broj vrtić4, obitelj: Časopisudžbenik za odgojčetvrti razred osnovne škole, Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Miklec, D., Jakovljević Rogić, Prtajin, G., Binder, S., Mesaroš Grgurić, N. i naobrazbu predškolske djece namijenjen stručnjacima i roditeljima, 4(16)Vejić, 10–13.

Roccella M.J. (2019). NeuropsychiatryMoj servicesretni ofbroj childhood and adolescence - Developmental Psychiatry.

Shaw, C.4, Brady,udžbenik L.-M.za ičetvrti Davey,razred C.osnovne (2011).škole, GuidelinesZagreb: forŠkolska research with children and young people. London: NCB Research Centre National Children’s Bureau.

Sithon, K. (2020). Understanding Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Children about COVID-19. Save the Children International: Cambodia.

Sprang, G., Silman, M. (2013). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents and Youth After Health-Related Disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(1), 105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22.

Wood, E. (2010). Developing integrated pedagogical approaches to play and learning. In E. Wood, P. Broadhead & J. Howard. Play and learning in the early years (1–9) London: Sage Publications Ltd.

World Health Organization. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak [PDF document]. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf.

World Health Organization. (2020). Mental health and psychological resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/mental-health-and-psychological-resilience-during-the-covid-19-pandemic#:~:text=Children%20are%20likely%20to%20be,mental%20well%2Dbeing.knjiga.

2. Međunarodna znanstvena i umjetnička konferencija Učiteljskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Suvremene teme u odgoju i obrazovanju – STOO2 - in memoriam prof. emer. dr. sc. Milanu Matijeviću, Zagreb, Hrvatska |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract |

|

Ever Considering the |

|

Key words |

|

|

Introduction

In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak an emergency for international public health. The World Health Organization has expressed concern for the high risk of the spread of COVID-19 in countries around the world. In March 2020, the World Health Organization evaluated that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic. The World Health Organization and the public health sectors around the world are involved in preventing the pandemic. However, this time of crisis is stressful for the entire population (WHO, 2020). Pandemics are rare, but they can devastating crises that can influence the lives of many children and their families physically, socially, and psychologically (Sprang and Silman, 2013). One of the vulnerable groups, who had to adjust to the pandemic swiftly, are children and adolescents (Sharma, Majumder, and Barman, 2020). Children are not indifferent to the dramatic effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. They experience fear, uncertainty, physical and social isolation, and may miss school for a long time. Understanding their reactions and emotions is essential to accordingly meet their needs (Jiao et al., 2020). Sprang and Silman (2013) collected data from a sample of 586 parents and their children’s psychosocial reactions to the pandemic disasters. In data collection, they used a mixed methodology: questionnaires, focus groups, and interviews. The survey results showcased that a large number of parents (44%) who had been in quarantine or isolation reported their children as not needing mental health care services, while the rest of the parents (33.4%) reported that their children started to use mental health care services connected to their own experiences during or after the pandemic. The most frequent diagnoses for these children were acute stress disorder (16.7%), adjustment disorder (16.7%), and grief (16.7%).

An early study of behavioral and emotional reactions of Chinese children during the COVID-19 epidemic was conducted in the Chinese province of Shaanxi. Given the restrictive measures of movement brought by the Chinese government to stop the further spread of COVID-19, parents filled out an online questionnaire about their children’s behavioral and emotional responses to the epidemic. The survey results of a sample of 320 children aged 3 to 18 years old showcased excessive parental attachments, distraction, irritability, and fear of asking questions about the epidemic as the most common behavioral and emotional problems. Furthermore, the results demonstrated excessive parental attachment and angst for possible infection of family members as symptoms more likely to develop in kindergarten children aged 3 to 6 years old (Jiao et al., 2020).

A study conducted on a sample of 1143 parents and children from 3 to 18 years of age, which analyzed immediate psychological effects of COVID-19 quarantine on Spanish and Italian youth, showcased that as many as 85.7% of parents noticed emotional and behavioral changes in their children during quarantine. The most frequent symptoms were concentration difficulties (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), restlessness (38.8%), nervousness (38%), feelings of loneliness (31.3%), and worry (30.1%) (Orgilés, Morales, Delvecchio, Mazzeschi, and Espada, 2020).

In their paper, Imran, Zeshan, and Pervaiz (2020) present the most prevalent symptoms of stress in young children during the pandemic. Young children most often exhibit stress in disapproval and irritability, inability to concentrate, as changes in sleep patterns, in waking up during the night, having nightmares, and in various regressive behaviors (such as thumb sucking, not controlling urination, and/or defecation, and demanding to be carried). In conclusion, the authors state that interventions should focus on nurturing resilience in children and adolescents by encouraging structure, routine and physical activity, and better communication to address children’s fears and concerns.

The 2020 study titled How does the COVID-19 pandemic affect the mental health of children and adolescents?, summarized relevant and available data on the mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing 51 topic-related articles. As expected, results determined different responses to stress in a different developmental stages. Yet, children of all developmental stages showcased a higher rate of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptoms, as would be expected after any highly traumatic occurrence (Marques de Miranda, da Silva Athanasio, Cecília de Sena Oliveira, and Simoes Silva, 2020).

In the United States, a nationwide survey was conducted in June 2020. Given the pandemic, the survey aimed to determine changes in the physical and emotional well-being of parents and their children. The results showed that 27% of parents reported deterioration of their mental health, while 14% reported their children’s behavioral problems as worsened. The deteriorated parents’ mental health coincided with children’s worse behavioral problems in nearly one in ten families (Patrick, Henkhaus, Zickafoose, Lovell, Halvorson, Loch, Letterie, & Davis, 2020).

Quarantine due to COVID-19 has had effects on the lives of most children and adolescents. They replaced friendships and routines of going to kindergarten or school with virtual social meetings and classes. Outdoor leisure was bound to the indoors. Closing-down was imperative to fight the pandemic, but the halt on social contact and the ban of going outside can have immediate psychological effects on children and adolescents. There were some public debates about whether the quarantine will affect children or whether they will be able to adjust to the new environment without excessive emotional strain. Knowledge about the effects quarantine has on the psychological welfare of children would aid professionals in implementing preventive measures (Orgilés et al., 2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) defines the current time as an increased stress-and-crisis time, stating that children are expected to be more demanding and needing more attention from their parents. Moreover, the World Health Organization recommends honest and age-appropriate conversations to ease their children’s anxiety. Overall, the knowledge base on children’s reactions to trauma and disastrous events is expanding, but the descriptions of their reactions during epidemics remain scarce (Klein, Devoe, Miranda-Julian, & Linas, 2009).

Given the previous research on psychosocial, behavioral, and emotional reactions of children during the COVID-19 epidemic – which results, due to the movement-restriction measures implemented to prevent further infection spread of COVID-19, were collected by parents filling out online surveys – this paper aims to research children’s perception on state of emergency caused by the Coronavirus. This research will use focus groups of children aged 4 to 6 years old as the method, bearing in mind the children’s expressed fear of asking questions about the epidemic (Jiao et al., 2020) and the World Health Organization’s advice of honest and age-appropriate conversation to alleviate stress and anxiety (WHO, 2020). Focus groups create a safe peer environment for children; the method can help avoid some power imbalances between researchers and participants, such as those between an adult and a child in a one-on-one interview Shaw, Brady, & Davey, 2011). Focus groups not only give researchers a large amount of data on a particular topic in a relatively short time but also encourage discussion and ask participants to explore and clarify their views (Clarke, 1999). It is an increasingly popular research method suitable for collecting data from children, young people, and parents (Adler, Salantera, and Zumstein-Shah, 2019). The goal of effective, or guided, focus groups are to express children’s voice and point of view on various topics (Kelly, 2013), and so the goal of the paper is to examine children’s perception of the state of emergency caused by the COVID-19 epidemic by the self-representation of participants used in the focus group research method.

Method

Participants

The participants were eight children from a kindergarten in Osijek-Baranja county. Children participated in a guided group discussion, in two focus groups on the 12th and 13th of May 2020, which was the first week in which children could return to the kindergarten after all of them closed down in the Republic of Croatia from 16th of March 2020 to 11th of May 2020. The age of the children ranged from 4 years to 6 years, and on average 5 years old (59 months). Three girls and five boys participated in the focus groups. The sample was convenient.

Procedure

The parents of all participants and participants themselves were familiarized with the objectives of the research and the parents gave written consents. Children were informed of the research aims and were asked about understanding what was explained to them, to which they gave informed verbal consent. Children were informed that they could stop participating in the research at any moment. Both focus groups lasted approximately 20 minutes, led by the research protocol in the kindergarten rooms. At the beginning of the discussion, children received puzzles to play with because some researchers noticed that giving children puzzles during discussions made them more relaxed, prompting them to have better and richer answers to the research questions (Morgan, Gibbs, Maxwell, and Britten, 2002).

The research protocol consisted of nine questions. At the beginning of the conversation, children were asked an introductory question: Will you talk to me a bit and solve the puzzle?, and then the transitional question: Do you know why you haven’t been to the kindergarten lately? Key questions followed: What is a virus? How can it harm us? Do you know how we get this virus? Can we do something not to get it? Have you talked to somebody about coronavirus? Are there any places you used to go to, but now you cannot because of the virus? Lastly, the children were asked the final question: Are you interested in anything else about the coronavirus? You can ask me any question if you want.

Content analysis results and discussion

The content of the audio recordings was listened to and transcribed using the computer program Nvivo. Qualitative content analysis inductively developed the following categories: 1. Knowledge of the virus, 2. Knowledge of the preventive measures, 3. Communication about the virus, 4. Emotions during the epidemic, 5. Strategies for dealing with negative emotions during the epidemic. The table shows an example of data organization, and in this way of data analysis, the conversations of the focus groups are concise and structured for a more easy interpretation.

Results

Example of data organization 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledge of the COVID-19 virus

A telephone survey, conducted from April to May 2020 on a sample of 241 children aged 10 to 17 years old, obtained the following results. All of the children did know about coronavirus, but only half (57%) knew that it was a virus that can cause serious illness. This raised concern given the fact that COVID-19 is a highly infectious virus. The survey results were surprising because they showcased that children of rural areas (61%) knew more about the virus than the children of urban areas (53%) (Sithon, 2020).

In this study, all eight children were familiar with coronavirus – they knew that they did not go to the kindergarten due to its outbreak and showed knowledge that the virus is in the whole world: It’s a disease in the city…in all cities. Additionally, as it was noted in the aforementioned research in which the children perceived the virus as dangerous (85%), this research as well reported children perceiving the virus as highly dangerous: I could get infected, be sick, and go to the hospital. Furthermore, children knew that the virus is infectious to both children and adults, and some even mentioned pets.

Researcher: Tell me, can this virus infect children?

Girl: Yes, kitties too.

Researcher: What do you think, for whom the virus is the most dangerous?

Girl: For a little baby.

Researcher: Do you think that it is more dangerous for a little baby or grandmas and grandpas?

Boy: For grandmas and grandpas.

Knowledge of the preventive measures

In this study, children listed several preventive measures. For instance, they listed staying at home, that is, minimizing the risk of infection: We have to protect ourselves, be at home. Apart from not being exposed to the virus, children noted hygiene habits and disinfectants: That we are at home, and I have disinfectants in the car and at the bed.; We have to wash our hands.

In research from Cambodia (2020), the majority of the children (99.2%) listed hand-washing and then mask-wearing (80.1%) as a preventive measure (Sithon, 2020). In this research, no child listed mask-wearing as a preventive measure against coronavirus, however, according to the recommendations of the Croatian Institute of Public Health, children from kindergarten children after the second year to early-school years are not obligated to wear masks. Appropriately, these children do not even perceive them as a preventive measure.

Communication about the COVID-19 virus

Communication with kindergarten children about the infections spread and the explanation of the disease should not only include the simplification of language and concepts but should also take into account children’s understanding of cause-and-effect relationships and diseases. From 4 to 7 years of age, children’s comprehension is under the influence of magical thinking, characterized by a child’s belief that thoughts, wishes, and unrelated actions can cause certain events. For example, a child can believe that specific thoughts or behavior can cause illness. Adults have to be aware of children’s developmental stages and be careful in explaining diseases so children would not unjustly blame themselves or feel as if the disease is a punishment for their misbehavior (Edwards and Davis, 1997). Thus, listening to children’s perceptions and beliefs about COVID-19 is crucial to provide them an accurate explanation that they can understand without unnecessarily feeling guilty or scared (Dalton, Rapa, and Stein, 2020). In this research, and regarding communication and information about coronavirus, children state their conversations with primary caretakers, relatives, and kindergarten teachers: I talked a little with mom and dad, they say you shouldn’t go out for the corona.; Yes (I talked), with mom, dad, grandma, and grandpa .; Kristina (kindergarten teacher) talked about it. In a study by Sithon (2020), the majority of the children reported social media and news as primary sources of coronavirus information, while fewer children reported their families. Given the age of these research participants, it is logical to assume communication with caretakers and family as a primary source of information because they are not yet able and not being age-appropriate for them to collect information from news or social media.

Emotions during quarantine

Long periods of quarantine can cause an increase in anxiety, fear of infection, frustration, boredom, isolation, and insomnia in children (Roccella, 2019). Children are vulnerable to the emotional effects of traumatic events, especially those that result in the closing of schools, social distancing, and house quarantines (Lubit, Defrancisci, and Eth, 2003). From statements of children in this study, it is evident that children articulated their emotions regarding the restrictive measures: I was sad because I couldn’t go outside.; I was sad because I didn’t go to kindergarten but I didn’t cry. Time of COVID-19 pandemic is a very unusual time for humanity, but especially for children that had to face huge life changes during the Corona crises. In the line of preventive measures, schools and kindergartens were closed down, which deprived children of a sense of structure, routine, incentives provided by educational institutions, and the feeling of social support from peers, educators, and school teachers. It is very likely that in this time, children will feel concerns, anxiety, and fear, i.e. types of fear often felt by adults, which include fear of death, fear of relatives dying, and fear of receiving medical help. As stated on the World Health Organization’s website (WHO, 2020), all of this contributes to the potential threat to mental health and children’s psychological resilience during the pandemic. These exact fears were felt by children in this research, as it is evident in a statement of a four-year-old boy: I missed my grandparents because I didn't go to them because I was afraid I would infect them if they didn't die. This sentence showcases that extremely young children felt fear of infection and death while experiencing the new normal in which they missed their loved ones whom they otherwise often saw. In addition to the fear of death, it could be observed that the children are worried about stopping the virus and that they are aware that the time of Corona crises could last.

Researcher: Do you think coronavirus is gone, and won’t come back?

Boy 1: But, they said that it will, during fall.

Girl 1: No, during winter

Girl 2: It passed a little.

Researcher: It passed a little, but it’ll come back?

Boy 1: Yes, but during winter, it won’t come back during summer. I guess Corona will go all the time now.

Boy 2: It will never pass.

Strategies for dealing with negative emotions during the epidemic

From the statements of the children in this research, it is noticed that they listed playtime as leisure time during quarantine: I was bored, so I played. Naturally, this is not surprising, given that in play children test various states, moods, and emotions. Play is seen as a form of "emotional hyperventilation." In the play, through "emotional hyperventilation," children play with feelings of fear, anxiety, and abandonment (Wood, 2010). Play is exceptionally important in a life of a child because it is more than just fun. It is a valuable part of the intellectual, social, and emotional development of the child (Petrović-Sočo, 1999), and so in times of crisis, play can help children deal with stress, anxiety, and crisis-related trauma (Chatterjee, 2018).

Graber et al. (2020) reviewed the works related to the effect of the quarantine and restrictive measures on child’s play and health well-being. They identified the following topics that relate to child’s play during restrictive measures: play availability, frequency of play behaviors, play as a means of expression, play as a support of social cohesion, play as a means of coping with stress, and skill development game. These authors state that it is precisely the play that could encourage coping with stress, expression, sociability, and skills development during periods of isolation or quarantine.

Conclusion

Children are a vulnerable group that experience fear, anxiety, uncertainty, and physical and social isolation during the Corona crises and may miss school and kindergarten for a long time. Understanding their reactions and feelings is indispensable to meet their needs (Jiao et al., 2020). With this information in mind, by using the qualitative research method of focus groups, this research aimed to comprehend children’s perception, experience, emotions, and knowledge relating to coronavirus, restrictive measures, and the new way of life that the pandemic requires. At the time of restrictive measures, it is troublesome to enter institutions and conduct research directly with very young children, so this research provides paramount insight into children’s perceptions of coronavirus and time spent in isolation from friends and kindergarten. In the future, it would be interesting to research a larger sample of children using a mixed methodology. Research of kindergarten children with current experiences and events may not be repeated, so such research must promptly be designed to understand the comprehension, knowledge, and fears of kindergarten children and respond accordingly in the future state of emergencies. Retrospective research of such situations is not so reliable because children may not be able to recall their experiences related to a particular topic of research.