The role of mindfulness and emotional intelligence in self-compassion

|

Teaching (Today for) Tomorrow: Bridging the Gap between the Classroom and Reality 3rd International Scientific and Art Conference |

|

Martina Gajšek, Tajana Ljubin GolubFaculty of education, University of Zagreb, Croatia martina.gajsek@ufzg.hr |

|

| Section - Education for personal and professional development | Paper number: 4 |

Category: Original scientific paper |

Abstract |

|

Positive psychology recognises self-compassion as a factor that promotes stress resilience and well-being. Thus, it seems important to study factors that promote students’ self-compassion, especially among those who are preparing for stressful and demanding professions such as preschool teaching. Some studies link mindfulness and emotional intelligence (EI) with self-compassion development, but there is a lack of studies that examine the role of individual EI dimensions in self-compassion as well as their mediating role in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to examine the role of mindfulness and EI dimensions in self-compassion. The second aim was to examine the mediating role of EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. 161 female students of the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb, studying early and preschool education, participated in the research (M = 25.79; SD = 6.42) by voluntarily and anonymously filling out the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, Emotional Intelligence Scale and Self-Compassion Scale. Regression analysis showed that mindfulness and three of the four EI dimensions (self-emotional appraisal, use of emotion and regulation of emotion) were significant predictors of self-compassion. Mediation analysis showed a partial mediation of mindfulness on self-compassion through the above mentioned three EI dimensions as parallel mediators. The findings of this study serve as the basis for directing greater attention of the educational process into the development of mindfulness and EI in order to promote students‘ self-compassion and, consequently, their readiness for the demands of the profession. |

|

Key words: |

| emotional intelligence, mindfulness, positive psychology, preschool teachers. |

Introduction

Self-compassion reflects being kind and understanding toward oneself amid life difficulties (Neff, 2003a). Through self-compassion one can restrain from self-criticism, over-identification with the experienced difficulties and isolating from others. Self-compassion is usually operationalized as a multidimensional construct that entails self-kindness, mindful awareness of painful experiences and recognizing that difficulties are part of the shared human experience (Neff, 2003a). Studies have confirmed that self-compassion relates to higher subjective and psychological well-being (e.g., Neff, 2003b; Tran et al., 2022). Positive psychology in education recognised self-compassion as a positive correlate of students’ stress resilience (Egan et al., 2021; McArthur et al., 2017), adaptive coping (Ewert et al., 2021; Neff, 2005) and various indicators of well-being (Fong & Loi, 2016; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Rahe et al., 2022). Thus, it seems important to study factors that promote self-compassion, especially among students who are preparing for stressful and demanding professions such as preschool teaching.

Previous studies linked self-compassion with mindfulness (Egan et al., 2021; Neff, 2003a; Tran et al., 2022). Mindfulness reflects a particular way of focusing attention and awareness on a present moment with a non-judgmental and non-reactive attitude towards ongoing experiences (Baer et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003). Although mindfulness is often studied as a momentary state that can be reached through meditative practice it can also be studied as a multifaceted disposition, i.e., a general tendency to be more mindful in everyday life (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Being mindfully aware, non-judgemental and non-reactive to all, including painful present-moment experiences, allows one not to get overwhelmed by or avoidant of them. This implies mindfulness as a necessary precursor of self-compassion (Biehler & Naragon-Gainey, 2022; Neff, 2003a). Previous studies found that self-compassion was positively related to either all facets of mindfulness (Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011) or some of the facets of mindfulness (McArthur et al., 2017), with total mindfulness being consistently positively associated with self-compassion (Egan et al., 2021; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; Martinez-Rubio et al., 2023; Tran et al., 2022).

Previous studies also related self-compassion with emotional intelligence (EI) (Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2011; Neff, 2003b; Şenyuva et al., 2013). EI is a part of social intelligence and refers to positive emotional resources and adaptive emotional functioning (Schutte & Loi, 2014). EI can be conceptualized twofold, as a trait (e.g., Petride & Furnham, 2000; Wong & Law, 2002), or as an ability (Mayer et al., 2004). There are several dimensions of trait EI, but the most common operationalization includes dimensions of perceiving and understanding emotions in self (SEA), perceiving and understanding emotions in others (OEA), regulation of emotion (ROE) and use of emotion for self-motivation (UOE) (Wong & Law, 2002). Previous studies found that individuals with higher levels of EI have greater mental health (Martins et al., 2010), better relationships with others (Lopes et al. 2004), as well as higher well-being (e.g., Schutte & Malouff, 2011) and flourishing both in general population (Du Plessis, 2023) and student population (Pradhan & Jandu, 2023; Zewude et al., 2024).

Self-compassion may also be related to EI since self-compassion entails recognizing and transforming painful experiences into self-kindness and self-understanding (Neff, 2003a). Overall trait EI was found to be consistently positively related to self-compassion (DiFabio & Saklofske, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2024), while the studies of the relationship between specific EI dimensions and self-compassion are somewhat scarce. To our knowledge, only one such study was conducted and found that specific dimensions of EI, i.e., self-management and self-motivation, were positively associated with all components of self-compassion (Şenyuva et al., 2011).

Based on the above presented, it seems that there is a lack of studies that examine the role of specific EI dimensions in self-compassion as well as their mediating role in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. Mindfulness was found to be related to EI both on overall (Baer et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003) and at the specific EI dimensions level (Cheng et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2015; Park & Dhandra, 2017). Even more, mindfulness was suggested as a factor that may encourage accurate perception of emotions, development of emotional regulation, and more adaptive emotional functioning (Park & Dhandra, 2017). In other words, mindfulness may lead to higher EI, and higher EI may lead to positive outcomes, such as higher self-esteem (Park & Dhandra, 2017). Based on this, it may also be posed that higher mindfulness would lead to higher EI, which would lead to higher self-compassion. However, the mediating role of EI in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion was not investigated.

Objectives

The first aim of this study was to examine the role of mindfulness and EI dimensions in self-compassion. The second aim was to examine the mediating role of EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. The hypotheses and research questions were as follows:

H1: Mindfulness is bivariately (1a) and uniquely (1b) associated with self-compassion.

H2: Overall emotional intelligence is positively associated with self-compassion.

H3: Mindfulness is bivariately associated with EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, OEA, ROE, UOE.

H4: EI is the mediator between mindfulness and self-compassion: Higher mindfulness leads to higher EI, which in turn leads to higher self-compassion.

RQ1: Which EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, OEA, ROE, UOE are bivariately (1a) and uniquely (1b) associated with self-compassion?

RQ2: Which EI dimensions, i.e., SEA (2a), OEA (2b), ROE (2c), UOE (2d) act as parallel mediators in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion?

Method

Participants and procedure

161 female students of the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb, studying early and preschool education, participated in the research (M = 25.79 years; SD = 6.42) by voluntarily and anonymously filling out the paper-pencil questionnaire during the regular academic semester.

Measures

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS, Brown & Ryan, 2003) was used to measure disposition to mindful attention and awareness. MAAS consists of 15 items (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”, reversed) which participants rated using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). The total score was calculated as a mean of all item ratings with higher results indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The scale was previously used in a Croatian sample and demonstrated good psychometric characteristics (Kalebić Jakupčević, 2014).

The Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS, Wong & Law, 2002) was used to measure four EI dimensions, i.e., self-emotion appraisal (SEA, e.g., I really understand what I feel), others’ emotion appraisal (OEA, e.g., I have good understanding of the emotions of people around me), use of emotions (UOE, e.g., I am a self-motivated person), regulation of emotion (ROE, e.g., I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties rationally). All 16 items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total average score for each WLEIS subscale was used as an independent indicator of each EI dimension. A higher result on each WLEIS subscale indicates a higher level of that EI dimensions.

The Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form (SCS–SF, Raes et al., 2011) was used to measure six components of self-compassion, i.e., over-identification (e.g., When I fail at something important to me I become consumed by feelings of inadequacy, reversed), self-kindness (e.g., I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like), mindfulness (e.g., When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation), isolation (e.g., When I’m feeling down, I tend to feel like most other people are probably happier than I am, reversed), common humanity (e.g., I try to see my failings as part of the human condition) and self-judgement (e.g., I’m disapproving and judgmental about my

own flaws and inadequacies, reversed). All 12 SCS-SF items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). A total self-compassion score was calculated as a mean of all subscale scores but omitting mindfulness subscale items, in order to avoid an artificial increase of correlation between the constructs of mindfulness and self-compassion, which is a common practice in such cases (e.g., Martínez-Rubio et al., 2023). A higher total result indicates a higher level of self-compassion.

Results

Descriptive statistics, correlations among the study variables, and Cronbach’s alpha

Descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations and Cronbach’s alphas are detailed in Table 1. The mean results showed that students reported moderate levels of mindfulness, both overall EI and specific EI dimensions as well as moderate levels of self-compassion. Mindfulness was positively bivariately correlated with self-compassion thus supporting Hypothesis 1a. Overall EI was bivariately positively associated with self-compassion, in line with Hypothesis 2. Mindfulness was also positively bivariately correlated with three of four EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, ROE and UOE, thus partially supporting Hypothesis 3. Regarding Research question 1a, all EI dimensions, i.e., SEA, ROE and UOE except OEA were positively bivariately correlated to self-compassion.

Table 1

Means, standard deviations and corelations between study variables.

|

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

|

1. Mindfulness |

- |

.28** |

.07 |

.29** |

.20* |

.31** |

.37** |

|

2. Self-emotion appraisals |

|

- |

.44** |

.47** |

.39** |

.76** |

.44** |

|

3. Others’ emotion appraisals |

|

|

- |

.22** |

.15 |

.59** |

.08 |

|

4. Regulation of emotion |

|

|

|

- |

.43** |

.73** |

.45** |

|

5. Use of emotion |

|

|

|

|

- |

.70** |

.53** |

|

6. Overall emotional intelligence |

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.50** |

|

7. Self-compassion*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

Theoretical range |

1-6 |

1-7 |

1-5 |

||||

|

Cronbach's alpha |

.79 |

.84 |

.79 |

.87 |

.90 |

.88 |

.82 |

|

M |

3.56 |

5.30 |

5.44 |

4.96 |

4.98 |

5.19 |

3.29 |

|

SD |

0.67 |

1.08 |

0.93 |

1.19 |

1.35 |

.82 |

0.64 |

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***Self-compassion scale with mindfulness items (item 3, item 7) omitted.

Regression analysis

A linear regression analysis was performed with mindfulness and four EI dimensions as predictors and self-compassion as criteria (Table 2). Together predictors explained 42% of the variance in students’ self-compassion (F5,155 = 22.69, p < 0.001). In line with Hypothesis 1b, mindfulness was a uniquely significant predictor of self-compassion. Regarding Research Question 1b, only EI dimensions of SEA, ROE and UOE were shown as uniquely significant predictors of self-compassion. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value for EI dimensions and self-compassion ranged from 1.13 to 1.64 indicating that all values are smaller than 10, meaning that there is no multicollinearity in the independent predictors.

Table 2

Regression analysis results with self-compassion as a criteria.

|

Predictors |

β |

|

Mindfulness |

.20** |

|

Self-emotion appraisals |

.23** |

|

Others’ emotion appraisals |

-.12 |

|

Regulation of emotion |

.16* |

|

Use of emotion |

.35** |

|

|

R² = .42** |

|

|

Adj. R² = .40** |

Note. β = standardized beta coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01.

Mediation analysis

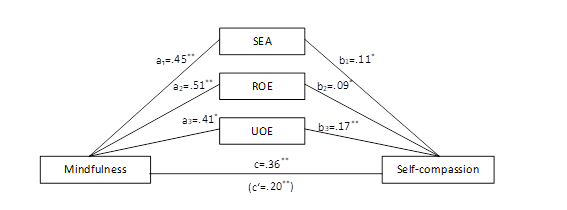

The results of the mediation analyses with EI dimensions of SEA, ROE and UOE, as parallel mediators between mindfulness and self-compassion are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 1. In line with Hypothesis 4, dimensions of EI mediated the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. In regard to Research Question 2, mediation analysis showed a partial mediation of mindfulness on self-compassion through the three EI dimensions, i.e., SEA (2a), ROE (2c) and UOE (2d) that acted as parallel mediators. The direct relation between mindfulness and self-compassion remained significant indicating the mediation was partial. Higher mindfulness fosters students’ self-compassion both directly, and indirectly via higher SEA, ROE and UOE. All mediators had a significant indirect effect on self-compassion. Although, UOE had the highest ratio of indirect to total effect (.19), specific indirect effect contrast analysis showed that the indirect effect of specific EI dimensions does not significantly differ from each other as shown in bootstrap method (with 5,000 bootstrap samples) at 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1

Mediating role of the three EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion

Note. SEA = self-emotional appraisal, ROE = regulation of emotion, UOE = use of emotion; non-standardized coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01. a relationship between predictor and mediator, b relationship between mediator and criteria, c total effect, c’ direct effect.

Table 3

Regression coefficients, standard errors, and confidence intervals for the indirect effects (mediators EI dimension: SEA, ROE, UOE)

|

|

B |

SE |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

Indirect effects |

|

|

|

|

|

Self-emotion appraisals |

0.05** |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.12 |

|

Regulation of emotion |

0.04** |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.11 |

|

Use of emotion |

0.07** |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

Note. B = non-standardized beta coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01; CI 95% confidence interval: LCI/UCI lower/upper confidence interval.

Discussion

This study contributes to an understanding of the relationship between mindfulness, dimensions of emotional intelligence and self-compassion.

As expected, the results showed that mindfulness was positively related to self-compassion, both bivariately and uniquely. These results are in line with previous research (Egan et al., 2021; Hollis-Walker & Colosimo, 2011; McArthur at al., 2017; Martinez-Rubio et al., 2023; Tran et al., 2022). Also as expected, results showed that overall EI was positively and moderately related to self-compassion, in line with previous studies (Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2021; Heffernan et al., 2011; Neff, 2003b; Thomas et al., 2024).

This study also revealed the relationship between specific EI dimensions and self-compassion. More precisely, results showed that three of four EI dimensions, i.e., perception and understanding of emotion in self, use of emotion for self-motivating purpose and self-regulation were bivariately and uniquely associated with self-compassion. These EI dimensions essentially represent ways in which a person is able to be compassionate toward self. Neff (2003a) argued that in order to experience self-compassion a person should be able to monitor and clearly apprehend their own emotions, and use that information to rapidly recover from painful experiences by transforming them into self-kindness and self-understanding (Neff, 2003). Therefore, this study’s results extend similar prior research (Şenyuva et al., 2011) which found that self-management and self-motivation are positively related to self-compassion and further suggest the crucial role of these EI dimensions for experiencing self-compassion.

In this study, the EI dimension of perception and understanding of emotion in others was not related to self-compassion. This could be because the applied Wong and Law (2002) OEA scale measures being perceptive and apprehending others’ emotions rather than using that information for influencing or managing others' emotions which is known to be usually positively related to self-compassion (e.g., Di Fabio & Saklofske, 2021). Also, this result is interesting from a developmental perspective since Maynard et al., (2022) study on an adolescent sample revealed a small but significant negative correlation (r = -.20**) between the ability to identify the emotional states of others and self-compassion. More specifically, their findings suggest that adolescents who demonstrate a heightened ability to perceive emotions in others, particularly negative emotions, experience lower levels of self-compassion and feelings of self-worth. Self-compassion varies depending on age (Tavers et al., 2024), and it may be that the relationship between self-compassion and OEA and other EI dimensions may also be different depending on age, but this should be further investigated.

The other main finding of the study is that of the partially mediating role of the EI dimensions in the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion. Results indicated that a higher level of mindfulness leads to a higher perception of emotion in self, higher use of emotions for self-motivation and a higher level of regulation of emotion, which all lead to a higher level of self-compassion. Park and Dhandra (2017) found that the tendency of mindful individuals to be attentive, present-focused, and non-judgmental makes them more capable of understanding and managing emotions well and utilizing these emotions and knowledge to prevent self-critical thoughts. Self-compassion requires that one does not harshly criticize the self in times of difficulty (Neff, 2003a). Also, Bao et al. (2015) obtained that mindful people have a better ability to regulate their emotions and make use of their emotions to motivate themselves, which enables them to perceive less stress. In university students’ higher mindfulness and self-compassion were also related to less perceived stress (Martínez-Rubio et al., 2023). Thus, it seems that mindfulness via the mentioned EI dimensions ensures a more emotionally balanced mindset needed to experience self-compassion rather than over-identification with negative experiences.

The result of partial mediation suggests that there may be also other mechanisms through which mindfulness may increase student’s self-compassion. Also, they point to the direct beneficial effect of mindfulness on self-compassion. Neff (2003a) theorized mindfulness as a necessary precursor to a self-compassionate response since mindfulness enables mental distancing from ongoing difficulties so that feelings of self-kindness and self-understanding can arise. Mental distancing, i.e., decentering reflects a shift in perspective associated with decreased attachment to one’s thoughts and emotions (Biehler & Naragon-Gainey, 2022; Brown et al., 2015). It is further posed that through decentering mindfulness may exert positive psychological outcomes, both directly and indirectly by mobilizing other psychological mechanisms, such as cognitive flexibility, values clarification, self-regulation, and exposure (Brown et al., 2015).

In this study, we theoretically posited that dimensions of EI precede self-compassion. However, it is also possible that at least some of the dimensions of EI have a bidirectional and circular relationship with self-compassion. For example, a higher level of self-compassion may lead to higher self-regulation, since self-compassion decreases stress (Poots & Cassidy, 2020) and self-regulation is better when a person is not under stress. Thus, it may well be that the relationship between self-regulation of emotion and self-compassion is circular.

Limitations and practical implications

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow us to draw any conclusions about the direction of causality in the associations observed. Further, longitudinal studies are required to reveal the dynamic reciprocal nature of all the study variables. Second, this study focused on EI as a trait. Since EI may be conceptualized also as ability, future studies may focus on such conceptualization of EI.

Per practical implications, since previous studies suggested that mindfulness, EI, and self-compassion can be trained (Nelis et al., 2011; Smeets et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2019), educational institutions may include knowledge about these concepts and offer training to students in order to further increase their self-compassion.

Conclusions

This study showed that dimensions of EI, i.e., perception and understanding of emotion in self, use of emotion for self-motivating purpose and self-regulation, mediated the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion, i.e., that higher mindfulness led to higher emotional intelligence, which in turn lead to higher self-compassion. These findings serve as the basis for directing greater attention of the educational process into the development of mindfulness and EI, especially dimensions of perception and understanding of emotion in self, use of emotion for self-motivating purpose and self-regulation, in order to promote students‘ self-compassion and, consequently, their readiness for the demands of the profession.

References

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Bao, X., Xue, S., & Kong, F. (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: The role of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 48–52.

Biehler, K. M., & Naragon-Gainey, K. (2022). Clarifying the relationship between self-compassion and mindfulness: An ecological momentary assessment study. Mindfulness, 13(4), 843–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01865-z

Brown, D. B., Bravo, A. J., Roos, C. R., & Pearson, M. R. (2015). Five facets of mindfulness and psychological health: Evaluating a psychological model of the mechanisms of mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6, 1021–1032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0349-4

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cheng, X., Ma, Y., Li, J., Cai, Y., Li, L., & Zhang, J. (2020). Mindfulness and psychological distress in kindergarten teachers: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), Article 8212. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218212

Di Fabio, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2021). The relationship of compassion and self-compassion with personality and emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, Article 110109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110109

Du Plessis, M. (2023). Trait emotional intelligence and flourishing: The mediating role of positive coping behaviour. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 49(0), Article a2063. https://doi.org/ 10.4102/sajip.v49i0.2063

Egan, H., O’Hara, M., Cook, A., & Mantzios, M. (2022). Mindfulness, self-compassion, resiliency and wellbeing in higher education: a recipe to increase academic performance. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1912306

Ewert, C., Vater, A., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2021). Self-compassion and coping: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12, 1063–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01563-8

Fong, M., & Loi, N. M. (2016). The mediating role of self‐compassion in student psychological health. Australian Psychologist, 51(6), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12185

Heffernan, M., Quinn Griffin, M. T., McNulty, S. R., & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2010). Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(4), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172x.2010.01853.x

Hollis-Walker, L., & Colosimo, K. (2011). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Personality and Individual differences, 50(2), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.033

Kalebić Jakupčević, K. (2014). Provjera uloge metakognitivnih vjerovanja, ruminacije, potiskivanja misli i usredotočenosti u objašnjenju depresivnosti [The role of metacognitive beliefs, rumination, thought suppression and mindfulness in depression]. (Doctoral disertation, Zagreb. Filozofski fakultet). Retrieved on 29th of March 2022 from https://www.bib.irb.hr/713854

Lopes, P. N., Brackett, M. A., Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., Sellin, I., & Salovey, P. (2004). Emotional intelligence and social interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264762

Martínez-Rubio, D., Colomer-Carbonell, A., Sanabria-Mazo, J. P., Pérez-Aranda, A., Navarrete, J., Martínez-Brotóns, C., Escamilla, C., Muro, A., Montero-Marin, J., Luciano, V. J., & Feliu-Soler, A. (2023). How mindfulness, self-compassion, and experiential avoidance are related to perceived stress in a sample of university students. Plos one, 18(2), Article e0280791. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280791

Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Marin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.029

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

Maynard, M. L., Quenneville, S., Hinves, K., Talwar, V., & Bosacki, S. L. (2022). Interconnections between emotion recognition, self-processes and psychological well-being in adolescents. Adolescents, 3(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3010003

McArthur, M., Mansfield, C., Matthew, S., Zaki, S., Brand, C., Andrews, J., & Hazel, S. (2017). Resilience in veterinary students and the predictive role of mindfulness and self-compassion. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0116-027R1

Neff, K. (2003a). Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and identity, 4(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021554

Park, H. J., & Dhandra, T. K. (2017). The effect of trait emotional intelligenceon the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and self-esteem. Mindfulness, 8(5), 1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0693-2

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448.

Poots, A., & Cassidy, T. (2020). Academic expectation, self-compassion, psychological capital, social support and student wellbeing. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101506

Pradhan, R. K., & Jandu, K. (2023). Evaluating the impact of conscientiousness on flourishing in Indian higher education context: Mediating role of emotional intelligence. Psychological Studies, 68(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00712-4

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2010). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Rahe, M., Wolff, F., & Jansen, P. (2022). Relation of mindfulness, heartfulness and well-being in students during the coronavirus-pandemic. International journal of applied positive psychology, 7(3), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-022-00075-1

Schutte, N. S., & Loi, N. M. (2014). Connections between emotional intelligence and workplace flourishing. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 134–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.031

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personality and individual differences, 50(7), 1116–1119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.037

Şenyuva, E., Kaya, H., Işik, B., & Bodur, G. (2014). Relationship between self‐compassion and emotional intelligence in nursing students. International journal of nursing practice, 20(6), 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12204

Smeets, E., Neff, K., Alberts, H., & Peters, M. (2014). Meeting suffering with kindness: Effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(9), 794–807. doi:10.1002/jclp.22076

Tang, Y-Y., Tang, R., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Promoting psychological well-being through an evidence-based mindfulness training program. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, Article 237. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00237

Tavares, L., Xavier, A., Vagos, P., Castilho, P., Cunha, M., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2024). Lifespan perspective on self-compassion: Insights from age-groups and gender comparisons. Applied Developmental Science, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2024.2432864

Thomas, C. L., Allen, K., & Sung, W. (2024). Emotional Intelligence and Academic Buoyancy in University Students: The Mediating Influence of Self-Compassion and Achievement Goals. Trends in Psychology, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-024-00363-6

Tran, M. A. Q., Vo-Thanh, T., Soliman, M., Khoury, B., & Chau, N. N. T. (2022). Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among Vietnamese university students: Psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators. Mindfulness, 13(10), 2574–2586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01980-x

Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243–274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1048-9843(02)00099-1

Zewude, G. T., Gosim, D., Dawed, S., Nega, T., Tessema, G. W., & Eshetu, A. A. (2024). Investigating the mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between internet addiction and mental health among university students. PLOS Digital Health, 3(11), Article e0000639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000639

|

Odgoj danas za sutra: Premošćivanje jaza između učionice i realnosti 3. međunarodna znanstvena i umjetnička konferencija Učiteljskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Suvremene teme u odgoju i obrazovanju – STOO4 u suradnji s Hrvatskom akademijom znanosti i umjetnosti |

|

Uloga usredotočene svjesnosti i emocionalne inteligencije u samosuosjećanju |

|

Sažetak |

|

U pozitivnoj psihologiji obrazovanja samosuosjećanje je prepoznato kao čimbenik u promociji otpornosti na stres i dobrobiti studenata. Stoga se čini bitnim istraživati faktore koji pospješuju razvoj samosuosjećanja studenata, posebice onih koji se pripremaju na stresne i zahtjevne pomagačke profesije kao što je odgajateljska. Neka istraživanja povezuju usredotočenu svjesnost (US) i emocionalnu inteligenciju (EI) s razvojem samosuosjećanja, no nedostaju istraživanja koja bi ispitivala ulogu pojedinih komponenti EI u samosuosjećanju te medijacijsku ulogu EI u odnosu US i samosuosjećanja. Stoga, prvi cilj rada bio je ispitati ulogu US i komponenti EI u samosuosjećanju. Drugi cilj bio je ispitati medijacijsku ulogu komponenti EI u odnosu između US i samosuosjećanja. U istraživanju je sudjelovalo 163 studenata Učiteljskog fakulteta u Zagrebu, studija ranog i predškolskog odgoja i obrazovanja (99% žena, M = 25.79; SD = 6.38), koji su dobrovoljno i anonimno ispunili anketni upitnik. Upitnik se sastojao od Skale usredotočene svjesnosti, Skale emocionalne inteligencije i Skale samosuosjećanja. Regresijske analize pokazale su da su US te tri od četiri komponente EI (prepoznavanje vlastitih emocija, korištenje emocija za samomotivaciju i samoregulacija emocija) značajni prediktori u objašnjenju individualnih razlika varijance samosuosjećanja. Medijacijske analize pokazale su da postoji parcijalna medijacija US na samosuosjećanje preko navedene tri komponente EI kao paralelnih medijatora. Rezultati ovoga istraživanja služe kao osnova za usmjeravanje veće pažnje u odgojno-obrazovnom procesu na razvoj usredotočene svjesnosti i emocionalne inteligencije studenata u svrhu razvoja samosuosjećanja i posljedično bolje spremnosti na zahtjeve profesije. |

|

Ključne riječi: |

|

emocionalna inteligencija, usredotočena svjesnost, odgojitelji, pozitivna psihologija |