Differentiation in English language teaching to young learners

Nina Klemen BlatnikPrimary School Mengeš, Mengeš |

|

Foreign languages education and research |

Number of the paper: 76 |

Original scientific paper |

Abstract |

|

Diversity is the cornerstone of the modern English classroom. Therefore, the differentiated instruction (DI), has become increasingly important in English language teaching to young learners. We perceive the differences in their preknowledge, understanding, skills, interests, learning profiles and other factors, which teachers must consider when planning DI. The principal aim of this article is to gain an insight into the basis on which teachers´ planning DI in Slovenia is based. The article investigates if and how these differences are seen by the authors of the curricula and the learning materials and how they are reflected in the lesson plans written by the publishing companies. In the empirical part, the descriptive method was used to present the research based on the material resources: English curricula, textbooks, workbooks, and exercise collections for English language teaching from the 1st to the 5th grade. The results reveal that the authors of the English curricula are aware of the individual differences among students. They have demonstrated them by writing down the standards, the minimum standards and a didactic recommendation in which the individualization and differentiation are mentioned. By analysing the learning materials, we found out that teachers, based on students' readiness and learning profile, almost equally often differentiate learning content and process. They do not differentiate the products. Most of the material is differentiated by difficulty, more than half by meaningfulness, some by flexibility and diversity, and rarely by thoroughness. |

|

Key words |

|

curriculum; EFL; lesson plan; primary school; learning materials |

Introduction

There are differences in preknowledge, understanding, skills, interests and learning profiles among students in a classroom (Tomlinson, 2014; Baker & Fleming, 2005), therefore it should be compulsory for all teachers to implement DI (Fautley & Savage, 2013). While many teachers understand that students learn in different ways and their needs are wide raging, not many teachers take that into consideration during everyday teaching practices (O`Rourke, 2015). Planning, executing, and implementing DI is a complex task where teachers perceive problems (Gaitas & Alves Martins, 2017; Gheyssens, E., Consuerga, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K., 2020). It is difficult to plan teaching in a way that adapts to the needs of each individual and maximize their learning opportunity (Baker & Fleming, 2005; Cowley, 2018; George, 2005; Tomlinson, 2014).

Studies have shown that “one size fits all” teaching is still often used in a classroom (Dijkstra, E. M., Walraven, A., Mooij, T., & Kirschner, A. P., 2017; Magablehg & Abdullah, 2020), causing boredom for some students (Kalin, 2006), falling behind for others (Doubet & Hockett, 2017), and also experiencing frustration and failure (Fox & Hoffman, 2011). The same problems seem to appear in teaching English as foreign language to young learners (aged 6 – 10), which led us to research how differentiation is defined in the curricula for English as a foreign language; furthermore, we wanted to know how authors of learning materials and lesson plans by publishing companies consider differentiation. The results of this study will help us implement DI for teaching English as a foreign language to young learners.

Planning process of differentiated instructions

To avoid situations where differences among students wouldn’t be considered while planning teaching, which can lead to low achivement rate and decreased level of motivation (Cardwell, 2012; Kotob & Jbaili, 2020; Meyad N. R., Roslan, S., Abdullah, M. C. & Hajimaming, P. 2014), detailed planning of teaching practise should be considered. It should be based on applicable regulations and high-quality curricula, which is the base for DI (Tomlinson, 2014), also it should push students above their zone of proximal development (Tomlinson, 2017).

Differentiation is defined in the Elementary education act (1996), in foreign language curriculum for 1st grade (2013a), foreign language curriculum for 2nd and 3rd grades (2013b) and curriculum for English as a foreign language (2016). The Elementary education act (1996) in its Article 2 defines providing conditions for personal growth of students according to their skills and interests as one of its main objectives, which coincides with principles of DI that aims to reach maximum student growth and individual success (Cowley, 2018; Heacox, 2009; Lupsa, 2018; Tomlinson, 2017). Article 40 determines DI to be followed not only in a classroom but also with other forms of organized teaching according to students’ skills for the whole duration of elementary school education. Teaching foreign language in small groups is permited in 4th and 5th grade, but not for more than one quarter of teaching hours, starting in 4th grade from the month of April.

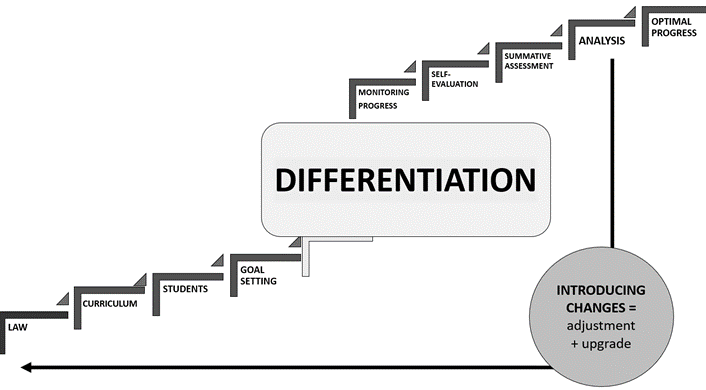

Planning lessons is a complex and demanding process (Baker & Fleming, 2005; Magajna & Umek, 2019), and implementing differentiation makes that process even harder (Khan & Jahan, 2017). Through the use of DI strategies teachers change and adapt curricula to meet the needs of all students (Heacox, 2009) and try to achieve optimal development of every student in a classroom (Cowley, 2018; Heacox, 2009; Fautley & Savage, 2013). Knowledge of legislation is as crucial as knowing the student (Heacox, 2009; Levine, 2003; Tomlinson, 2014; van Geel, M., Keuning., T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher, A. J., 2019), knowing objectives determined in curricula and standards of knowledge that should be the means to achieve broad, related, in-depth and permanent knowledge (Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Tomlinson, 2014). Based on the above, teachers determine the important elements for students to learn, understand and be able to do: CONTENT (what we teach), PROCESS (how we teach) and PRODUCT (learning outcomes) (Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Heacox, 2009; Levy, 2008; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010; Tomlinson, 2003). It is important to monitor student’s progress and analyse it. This enables constant adjustment and upgrade of learning methods according to student’s success, progress and needs (Gaitas & Alves Martins, 2017; van Geel et al., 2019) together with student’s self-evaluation that helps them recognize their achivements and their objectives and also boosts their motivation and self-image (Shen & Zhang, 2020). Based on these theoretical points about differentiation and planning process we developed a model of planning process of DI presented below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of planning process of DI.

What to differentiate, on what basis and how?

While planning the content, teachers consider knowledge and skills students should aquire, topics included in the curriculum, resources and materials used, and concepts they would discuss with students. Special attention should be given to the fact that content is synchronized with set goals, that it is suitable, interesting, understandable, related to preknowledge, transferable into practise, useful, diverse, convincing and authentic. That can be provided with varied texts and extra resources on different levels of difficulty (normal, in-depth, advanced) with different online and audiovisual resources, interesting concepts, short lessons, extra explanations for low achievers, skipping learning content for high achievers, making sure students have the possibility of in-depth study ...

While planning the process, teachers often wonder how to teach certain content so that students would understand the information, ideas and skills presented, while keeping learning styles close to students’ needs and interests. Assignments and activities should be focused on setting goals and be related to the content, planned on different levels of difficulty (according to Bloom's taxonomy), especially targeted, diversed, of good quality, meaningful and given in the appropriate order. Teachers can achieve that with different support strategies, agreements, learning contracts, flexible learning groups, encouraging students to be more creative, competitive, but also cooperative and critical in their thinking. It’s important to include students in all activities in as many ways as possible to enable them to practice and achieve results in different ways (Dudley & Osváth, 2016; Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Heacox, 2009; Tomlinson, 2014).

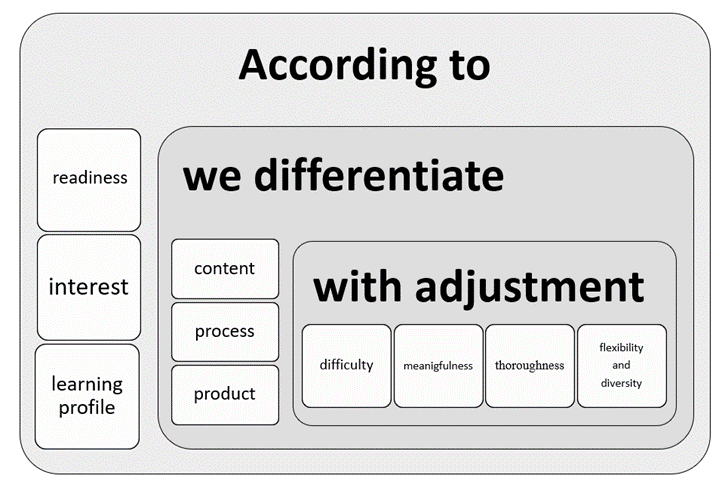

During planning of products, teachers often ponder in what way students will show what they’ve learned, what they know and what they can do, also how they understand things. It is necessary to think that way so teachers can be clear on what they can expect of all students and what of certain individuals (Heacox, 2009; Tomlinson, 2014), because it would be unfair to expect the same results from everyone in the group (Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Wormeli, 2006). The summative assessment is based on clear learning objectives closely related to content through which students can demonstrate what they learned in an authentic way (presented through dialog, oral presentation, role playing or posters), either doing it alone, in pairs or in a group and through that expressing in areas where they are the strongest (according to Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences) in an innovative and unique way (Tomlinson, 2014). Teachers can prepare a set of exercises listed by different levels of complexity so students choose the ones through which they could best show their skills and knowledge (Dudley & Osváth, 2016). Teachers should plan assignments based on high expectations (Bleck & Boakes, 2010) and also pay attention to establishing safe and encouraging learning environment, which according to Gaitas & Alves Martins (2017) can be easier task than adjusting other criteria, but nevertheless it has an important influence on students’ self-image and consequently on better learning results (Dudley & Osváth, 2016). Teachers can adjust elements described above according to standards and curricula with strong consideration of students’ readiness (level of preknowledge, understanding and skill), interests (topics that excite students), learning profile (learning style, learning pace, type of intelligence, gender, cultural background) (Baker & Fleming, 2005; Doubett & Hockett, 2017; Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Levy, 2008; Tomlinson, 2004; Tomlinson, 2014; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010), personality (self-confidence, effort) and motivation (Bosker, 2005 in van Geel, 2019; Heacox, 2009). Content, process and product are differentiated based on students’ readiness, interest and learning profile while adjusting difficulty, meaningfulness, thoroughness, flexibility and diversity (Heacox, 2009). According to the theories of Tomlinson (2014) and Heacox (2009) we developed a model of DI that shows us what to differentiate, on what basis and how.

Figure 2. Model of DI (according to the theories of Tomlinson, 2014 and Heacox, 2009).

Definition of this study’s problem, its objectives and purpose

Differentiation enables students to learn according to their needs; better time management; appropriate level of difficulty and challenge; more learning opportunities; increases their motivation and inclusion; enables them to achieve higher level of progress and have more personalized learning experience (Cowley, 2018; Fox & Hoffman, 2011; Gregory & Chapman, 2013; Heacox, 2009; Tomlinson, 2014; van Geel et al., 2019). On the other hand, it is a complex skill that teachers claim to include into their teaching practises, but according to studies realization is far lower than expected or claimed (Baker & Fleming, 2005) and most teachers don’t know how to actually use this skill (Kalin, 2006; van Geel et al., 2019).

The requirement for the use of differentiation is stated in all three valid curricula for teaching English as a foreign language (2013a, 2013b, 2016). Our goal is to see how and to what extent the diversity of students is taken into account in curricula for English as a foreign language and how it is represented in learning materials and lesson plans offered by publishing companies. Based on acquired data we will be able to determine what the critical points are in planning of DI and where more attention should be focused in the future when new strategies and their implementation are planned.

Research questions

The implementation of DI in teaching English language to young students was determined indirectly with the analysis of different written resources (curricula, textbooks, workbooks, collection of exercises and tasks, lesson plans). Based on literature review we pose these research questions:

RQ1: In what way diversity of students is included in curricula?

RQ2: How and to what extent diversity of students is taken into account and represented in learning materials for teaching English to young students?

RQ3: How diversity of students is taken into account in lesson plans offered by publishing companies?

Methods

Research methods

A descriptive method of empirical research was used.

Material resources

To answer the first research question, we used written resources: foreign language curriculum for 1st grade (2013), foreign language curriculum for 2nd and 3rd grade (2013) and curriculum for English as a foreign language (2016).

To answer the second research question, we analised 41 textbooks, workbooks, and collection of worksheets intended for students from 1st to 5th grade.

To answer the third research question, we analised 180 lesson plans that publishing companies offer teachers who use their textbooks and workbooks (online or in a book).

Data collection process

All three curricula for foreign language teaching were analised to determine whether differences between students were being considered and how exactly that has been done. We searched for parts of text related to the idea of differentiation and specific mentions of differentiation within curricula.

Analysis of written resources (textbooks, workbooks, collections of worksheets and lesson plans) was done based on our own evaluation instrument that is based on complexity of differentiaton factors based on a theory by Tomlinson (2014), elements of adjustment by Heacox (2009) according to curriculum guidelines for English as foreign language (2013a, 2013b, 2016). We wanted to examine if specified standards were differentiated (standards, minimal standards), if exercises were marked according to their level of complexity, what (content, process, product) and based on what (readiness, interest, learning profile) and in what way (difficulty, meaningfulness, in-depth, flexibility, diversity, support) teachings are being differentiated, also what ways of knowledge assessment are suggested (diagnostic, formative, summative). We believe these indicators of differentiation are suitable for forming indirect conclusions (analysis of curricula, materials, lesson plans). The analysis was done by one person. The evaluation instrument was examined by a professor of English at the Faculty of Education, University of Primorska.

Results and interpretation

Differentiation in curricula

Teachers’ planning is based on curricula; therefore, their in-depth knowledge is crucial. For successful planning of DI, we had to review all three valid curricula for teaching English as a foreign language (2013a, 2013b, 2016). We were searching for instructions in what way teachers should consider all of students’ differences; we also searched for any text that is directly or indirectly related to the subject of differentitation. All three curricula have the same structure, and they upgrade each other. The word differentiation is indirectly mentioned in the definition of the subject, where it is written that teaching and learning of a foreign language should be based on personalization and individualization (2013a; 2013b), taking into regard the growing diversity of students based on language or cultural differences (2016). Differentiation and individualization are highlighted in all three curricula among didactic recommendations. Curricula recognize the problem of heterogeneity (regarding knowledge, skills and understanding). Heterogeneity is defined by internal factors (ability, skill, cognitive style, motivation, learning interests, general knowledge, preknowledge, attitude towards native speakers and their culture) and by external factors (implementation of optional subject in the 1st grade, implementation of enriched curriculum in the preschool period, familiarity with a foreign language, opportunities to learn and use a foreign language in practice). Recommendations suggest testing students for preknowledge and skills. Differentiation (customized content, approaches, and methods to every student’s individual level) in the 1st and 2nd grade should be concentrated on the process of planning, implementing, and testing of progress; from 3rd grade on it should also be included in the assessment of knowledge. Special attention should be paid to specific groups of students (gifted students, students with learning difficulties, students with deficit in knowledge in certain areas, immigrants) to avoid danger of undifferentiated teaching that can lead to loss of motivation for learning, slower progress and bigger chance of becoming a distraction in class. Differentiation is clearly stated in all three curricula under a chapter dedicated to standards of knowledge.

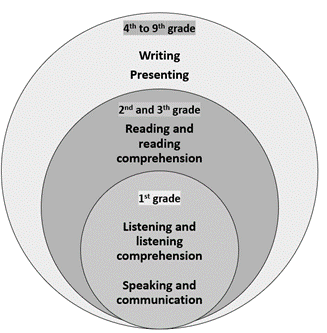

In a chapter about standards of knowledge minimal standards (that all students should achieve) are specified for some skills, also basic standards (an everage student should achieve), whereas higher standards are not specified. In a foreign language curriculum for the 1st grade (2013a) and curriculum for a foreign language for 2nd and 3rd grade (2013b) minimal standards are bolded, whereas in curriculum for English as a foreign language (2016) minimal standards and basic standards are stated separately. Standards of knowledge are the same in all curricula for foreign language for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade regarding listening and listening comprehension, speaking and communication with the exception of a standard called – Student detects text in a foreign language. In the 1st grade this standard is categorized as minimal standard, whereas in 2nd and 3rd grade is categorized as basic standard. In 2nd and 3rd grade standards of knowledge are upgraded with standards for reading and reading comprehension.

The curriculum for English as a foreign language contains standards of knowledge for different skills that are divided in 2 groups: for students from 4th to 6th grade and for student from 7th to 9th grade. They are upgraded with standards for writing and presenting (mediation). It is important to keep in mind that not all students’ progress is the same, depending on individual’s linguistic skills (2016).

Figure 3. Model of upgrading standards of knowledge by skills.

Indirectly differentiation is mentioned among the benefits of learning a foreign language at an early age (2013b), as well as among general goals, operational goals, contents (2016) and in didactic recommendations (2013a, 2013b, 2016). Among the benefits of learning a foreign language at an early age encouraging and safe learning environment, encouraging and effective feedback and authentic didactic materials that meet students’ interests and their cognitive abilities as well learning style, are highlighted (2013 b). General goals emphasize the importance of knowing different cultures and accepting difference and tolerance for diverse opinions; comparing languages and developing analytical thinking skills is also important, as is awareness of responsibilities for learning and knowledge, also making sense of learning material and implementing it into everyday life. Students should learn to use information and communication technology to obtain information, develop organizational skills, they should be able to solve problems and be innovative. Use of support that should be slowly withdrawn is mentioned in operational goals, as are diversity of texts (according to theme and level of difficulty) and diversity of responses (2016). Content is not specifically defined. Topics can be selected by teachers and students. Returning to different topics is advisable as is in-depth and abstract review with more demanding cognitive activities (2016). Didactic recommendations emphasize the importance of inclusion of different forms of learning, team work among teachers, diverse language experience, maintenance of inner motivation, encouragement for research, expression of their experience and insight, encouragement of students to be more mentally active, development of intercultural competence (2013a; 2013b), acceptance of students as equal conversationalists, expension of their vocabulary, and differentiation of homework (2016). Regarding testing and knowledge assessment the meaning of principles of formative assessment is emphasized. Inclusion of student’s interests is also important, as is encouragement of curiosity and creativity, knowing one’s learning goals, cooperation in setting and achieving goals, defining, and applying evalution criteria, self-evaluation of students, analysis of test results and planning of follow-up activities depending on results (2013a; 2013b; 2016).

Differentiation in learning materials

Teaching materials for 1st to 3rd grade

Table 1. Number of collected points according to what learning materials for 1st to 3rd grade most often differentiate

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

f |

f % |

F |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

content |

60 |

42.0% |

83 |

58.0% |

143 |

100.0% |

|

process |

63 |

40.4% |

93 |

59.6% |

156 |

100.0% |

|

product |

0 |

0% |

39 |

100.0% |

39 |

100.0% |

Results show that learning materials for 1st to 3rd grade equally differentiate content (f% = 42.0%) and process (f% = 40.4%), on the other hand, product is never differentiated.

Table 2. Number of collected points based on what learning materials for 1st to 3rd grade most often differentiate

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

F |

f % |

f |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

readiness |

75 |

48.1% |

81 |

51.9% |

156 |

100.0% |

|

interest |

9 |

8.7% |

95 |

91.3% |

104 |

100.0% |

|

learning profile |

40 |

51.3% |

38 |

48.7% |

78 |

100.0% |

Most often differentiation is based on learning profile (f% = 51.3%), a less often differentiation is based on readiness (f% = 48.1%), but it is rarely based on interest (f% = 8.7%).

Table 3. Number of collected points according to what learning materials for 1st to 3rd grade are most often adjusted

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

f |

f % |

f |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

difficulty |

45 |

86.5% |

7 |

13.5% |

52 |

100.0% |

|

meaningfulness |

30 |

57.7% |

22 |

42.3% |

52 |

100.0% |

|

thoroughness |

2 |

3.8% |

50 |

96.2% |

52 |

100.0% |

|

flexibility and diversity |

42 |

26.9% |

114 |

73.1% |

156 |

100.0% |

Most adjustments are based on level of difficulty (f% = 86.5 %), followed by adjustments according to meaningfulness (f% = 57.7%), flexibility and diversity (f% = 26.9%), whereas thoroughness is rarely adjusted (f% = 3.8%).

Teaching material for 4th to 5th grade

Table 4 . Number of collected points according to what learning materials for 4th and 5th grade most often differentiate

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

F |

f % |

f |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

content |

67 |

50.8% |

65 |

49.2% |

132 |

100.0% |

|

process |

71 |

49.3% |

73 |

50.7% |

144 |

100.0% |

|

product |

0 |

0% |

36 |

100.0% |

36 |

100.0% |

Results show that learning materials for 4th and 5th grade equally differentiate content (f% = 50.8%) and process (f% = 49.3%), on the other hand, product is never differentiated.

Table 5. Number of collected points based on what learning materials for 4th and 5th grade most often differentiate

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

f |

f % |

f |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

readiness |

88 |

61.1% |

56 |

38.9% |

144 |

100.0% |

|

interest |

13 |

13.5% |

83 |

86.5% |

96 |

100.0% |

|

learning profile |

36 |

50.0% |

36 |

50.0% |

72 |

100.0% |

Most often differentiation is based on readiness (f% = 61.1%), less often differentiation is based on learning profile (f% = 48.1%), but it is rarely based on interest (f% = 13.5%).

Table 6. Number of collected points according to what learning materials for 4th and 5th grade are most often adjusted

|

YES |

NO |

SUM |

||||

|

f |

f % |

F |

f % |

f |

f% |

|

|

difficulty |

45 |

93.8% |

3 |

6.2% |

48 |

100.0% |

|

meaningfulness |

31 |

64.6% |

17 |

35.4% |

48 |

100.0% |

|

thoroughness |

12 |

25.0% |

36 |

75.0% |

48 |

100.0% |

|

flexibility and diversity |

37 |

25.7% |

107 |

74.3% |

144 |

100.0% |

Most adjustments are based on level of difficulty (f% = 93.8 %), followed by adjustments according to meaningfulness (f% = 64.6%), flexibility and diversity (f% = 25.7%) and thoroughness (f% = 25.0%).

Diferentiation in lesson plans offered by publishing companies

We analysed 180 different lesson plans that publishing companies offer teachers who use their textbooks and workbooks; online or in manuals. The evaluation instrument was the same as for the research question 2.

The analysis showed that lesson plans don’t implement DI, exept for one learning material, otherwise they are poorly written, their main focus is completion of exercises in textbooks and workbooks, some exercises are sometimes added, but mostly they consist of numerous exercises that are not differentiated. Only lesson plans written by one publishing company upgrade learning material according readiness, interest and learning profile. They differentiate exercises in three levels of difficulty and based on different learning styles. Lesson plans in manuals have more quality but even there the lack of differentiation is significant. Lesson plans materials from foreign publishing companies include numerous extensions, review exercises, additional material and teaching tips that were missed in manuals and lesson plans material from Slovene publishing companies. We were also expecting inclusion of more differentiated and interesting exercises, bigger differentiation of products, also more frequent encouragement of students to think and actively participate and cooperate. While analysing lesson plans we detected more examples of diagnostic assessments in a form of brainstorming than in textbooks. There were word lists with known vocabulary, and also more of comprehension test with pictures. More precise definition of summative assessment of knowledge was not given. Futhermore, we miss more active participation of students in the whole learning process.

Conclusions

Our study shows that curricula for English as a foreign language detect differences among students, are focused on significance of differentiation and its instructions, with separate definitions of standards and minimal standards, with indirect and direct focus on the elements of differentiation, with consideration of different speed of students’ progress according to their abilities, with openness regarding content and spotlighting the danger of undifferentiated teaching they also offer a quality basis for differentiated content, process and product according to knowledge, interests and learning profiles. Quality curricula are the base for differentiation (Tomlinson, 2017) that is why our study aimed to find out if quality base is enough for quality implementation of differentiation in practice.

Quantitative analysis of learning materials showed consideration of differences among students regarding content and process in approximately half of the analysed learning materials. On the other hand, product is never differentiated. Most often differentiation is based on learning profile, only a little less on readiness and very rarely on interests. Most adjustments are based on difficulty, two-thirds on meaningfulness, one-third on flexibility and diversity, while thoroughness adjustments are rare. Based on our research we can conclude that more emphasis will need to be placed on product differentiation based on student interests. Therefore, we suggest that students should be more included as a central figure of the teaching process, which was previously suggested by Marentič Požarnik (2004). In this way we will get more active and motivated students.

In higher grades, they differentiate more often on the basis of readiness and less often on the basis of learning profile. Adaptation of tasks according to all selected criteria is also increasing, but thoroughness, flexibility and diversity still remain a very rarely used form of differentiation.

Our findings show that only one publishing company’s lesson plans include adjustments according to specific groups, others only suggest following the exercises in learning materials. Manuals are more detailed and include a variety of different ways a lesson could be taught. They even highlight critical points in teaching process, and yet most of them still neglect differentiation strategies. Learning materials can be implemented into teaching process in different ways. Therefore, we expected that more elements of differentiation would be included into lesson plans than in the learning materials.

The contribution of this study and its limitations

The purpose of this study was to get a general overview of the implementation of differentiation and consideration of students’ differences in teaching English as a foreign language from 1st to 5th grade. The study gave us a general insight into the researched topic and elements of differentiation that teachers don’t pay enough attention to.In the future neglected aspects should be thoroughly researched, their effective implementation into pedagogical practice of learning English at an early age should also be considered. While analysing lesson plan materials provided by publishing companies we realized it would be more appropriate to analyse teachers’ lesson plans to get a more direct insight into what is happening during lessons, but we could not provide enough material.

The analysis of learning materials and lesson plans was done by one person that used their own evaluation instrument. Therefore, we have to acknowledge that the results of the study could be different, if another person would be analysing the same materials using their own evaluation instrument.

Further possibilities of research

The focus of possible further studies should be directed into researching the reasons for less frequent use of certain elements of differentiation. It would also be useful to make a holistic model of DI according to the newest theories of foreign languages teaching to young learners and make thorough consideration of how this should be implemented into practice. That is also what Baker and Fleming (2005) and Smets and Struyven (2020) highlight as the most challenging part.

References

Al-Subaiei, M. S. (2017). Challenges in Mixed Ability Classes and Strategies Utilized by ELI Teachers to Copewith Them. English Language Teaching, 10(6), 182–189.

Baartman, L. K., Bastiaens, T. J., Kirschner, P. A., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. (2006). The wheel of competency assessment: Presenting quality criteria for competency assessment programs. Studies in educational evaluation, 32(2), 153–170.

Baker, P. H., & Fleming, L. C. (2005). Lesson plan design for facilitating differentiated instruction.MIDWESTERN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER, 18(4), 35.

Blažič, M., Ivanuš Grmek, M., Kramar, M., & Strmčnik, F. (2003). Didaktika – visokošolski učbenik. Novomesto: Visokošolsko središče, Inštitut za raziskovalno in razvojno delo.

Blecker, N. S., & Boakes, N.J. (2010). “Creating a Learning Environment for All Children: Are TeachersAble and Willing?” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(5), 435–447.

Bourke, R., Mentis, N., & Todd, L. (2011). “Visibly Learning: Teachers’ Assessment Practices for Students with High and Very High Needs.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(4), 405–419.

Caldwell, D. W. (2012). Educating gifted students in the regular classroom: Efficacy, attitudes, and differentiation of instruction. Electronic Theses & Dissertations. Paper 822.

Cowley, S. (2018). The Ultimate Guide to Differentiation: Achieving Excellence for All. BloomsburyPublishing.

Dijkstra, E.M., Walraven, A., Mooij, T., & Kirschner, A. P. (2017). Factors affecting intervention fidelity of differentiated instruction in Kindergarten. Research Papers in Education, 32(2), 151–169.

Doubet, K. J., & Hockett, J. A. (2017). Differentiation in the elementary grades: Strategies to engage andequip All learners. ASCD.

Dudley, E., & Osváth, E. (2016). Mixed Ability Teaching-Into the Classroom. Oxford University Press.

Fautley, M., & Savage, J. (2013). Lesson planning for effective learning. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Fox, J., & Hoffman, W. (2011). The differentiated instruction book of lists (Vol. 6). John Wiley & Sons.

Gaitas, S., & Alves Martins, M. (2017). Teacher perceived difficulty in implementing differentiatedinstructional strategies in primary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(5), 544–556.

George, P. S. (2005). A rationale for differentiating instruction in the regular classroom. Theory Into Practice, 44(3), 185–193.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020). Good things come to those who wait: the importance of professional development for the implementation of differentiatedinstruction. Frontiers in Education, 5, 96.

Gregory, G. H., & Chapman, C. (2013). One size doesn't fit all. Differentiated instructional strategies: Onesize doesn't fit all. Corwin press.

Heacox, D. (2009). Diferenciacija za uspeh vseh. Ljubljana: Rokus Klett.

Kalin, J. (2006). Možnosti in meje notranje učne diferenciacije in individualizacije pri zagotavljanju enakihmožnosti. Sodobna pedagogika, 57, 78–93.

Khan, I., & Jahan, A. (2017). Relevance of differentiated instructions in english classrooms: an exploratorystudy in the saudi context. International research journal of human resource and socialsciences, 4.

Kotob, M. M., & Jbaili, F. (2020). Implementing Differentiation in Early Education: The Impact on Student’s Academic Achievement. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 7(2), 110–133.

Krashen, S. D. (1973). Lateralization, language learning, and the critical period: Some new evidence.Language learning, 23(1), 63–74.

Kubale, V. (2016). Priročnik za sodobno oblikovanje ali artikulacijo učnega procesa. Celje: samozaložba

Levy, H. M. (2008). Meeting the needs of all students through differentiated instruction: Helping everychild reach and exceed standards. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issuesand Ideas, 81(4), 161–164.

Luspa, D. (2018). Mixed ability classes in efl learning: problems and Solutions. Esteem: Journal of EnglishStudy Programme, 1(1).

Magajna, Z., & Umek, M. (2019). Učne priprave na nastope bodočih učiteljev. Journal of ElementaryEducation, 12(3), 325–350.

Mahmanazarova, F. (2018). Possible problems in mixed-ability classes. Вопросы науки и образования, 8, 130–132.

Marentič Požarnik, B. (2004). Konstruktivizem v šoli in izobraževanje učiteljev. Univerza v Ljubljani, Filozofska fakulteta, Center za izobraževanje učiteljev. Ljubljana.

Magableh, I. S. I., & Abdullah, A. (2020). Effectiveness of differentiated instruction on primary school students’ English reading comprehension Achievement. International Journal of Learning,Teaching and Educational Research, 19(3), 20–35.

Meyad, N. R., Roslan, S., Abdullah, M. C., & HajiMaming, P. (2014). The effect of Differentiated LearningMethod in Teaching Arabic Language on Students' Motivation. Journal of Social Sciences Research, 5(1), 671–678.

O’Rourke, J. (2015). “Inclusive Schooling: If It’s So Good – Why Is It So Hard to Sell?” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(5), 530–546.

Parsons, S. A., Vaughn, M., Scales, R. Q., Gallagher, M. A., Parsons, A. W., Davis, S. G., … Allen, M. (2018). Teachers’ instructional adaptations: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 205–242.

Skribe Dimec, D. (2013). Diferenciacija pri poučevanju naravoslovja v prvem in drugem vzgojno-izobraževalnem obdobju osnovne šole. Journal of Elementary Education, 6.

Smets, W., & Struyven, K. (2020). A teachers’ professional development programme to implement differentiated instruction in secondary education: How far do teachers reach?. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1742273.

Učni načrt. (2013a). Program osnovna šola. Tuji jezik v 1. razredu. Ljubljana: Ministrstvo za izobraževanje, znanost in šport: Zavod Republike Slovenije za šolstvo. Retrieved on 21st January 2021 from http://osfeng1.splet.arnes.si/files/2019/07/TJ_prvi_razred_izbirni_neobvezni.pdf

Učni načrt. (2013b). Program osnovna šola. Tuji jezik v 2. in 3. razredu. Ljubljana: Ministrstvo za izobraževanje, znanost in šport: Zavod Republike Slovenije za šolstvo. Retrieved on 21st January 2021 from https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MIZS/Dokumenti/Osnovna-sola/Ucninacrti/obvezni/UN_TJ_2._in_3._razred_OS.pd

Učni načrt. (2016). Program osnovna šola. Angleščina. Ljubljana: Ministrstvo za izobraževanje, znanost inšport: Zavod Republike Slovenije za šolstvo. Retrieved on 21st January 2021 from https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MIZS/Dokumenti/Osnovnasola/Ucninacrti/obvezni/UN_ anglescina.pdf

van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher, A. J. (2019). Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction. School effectiveness and schoolimprovement, 30(1), 51–67.

Retelj, A., & Puljić, B. K. (2016). » Potrebujemo več prakse!« Kako bodoče učiteljice in učitelji nemščine vrednotijo svoje izkušnje z mikropoučevanjem?. Journal of Elementary Education, 9(4), 139–154.

Sherin, M. G., & Drake, C. (2009). Curriculum strategy framework: investigating patterns in teachers’ useof a reform-based elementary mathematics curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 41(4), 467–500.

Shen, Q., & Zhang, J. (2020, July). A Good Lesson Plan is Half Done. In 2020 International Conference on Advanced Education, Management and Social Science (AEMSS2020), (pp. 16–18). Atlantis Press.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2003). Teach them all. Educational Leadership, 61(2), 7–9.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2004). “Point/Counterpoint: Sharing Responsibility for Differentiating Instruction.”Roeper Review, 26(4).

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms. Alexandria: ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.

Whipple, K. A. (2012). Differentiated instruction: A survey study of teacher understanding and implementation in a southeast Massachusetts school district (Doctoral dissertation) Northeastern University.

Wormeli, R. (2006). Fair isn’t Always Equal: Assessing and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Zakon o osnovni šoli. Uradni list RS, št. 81/06 uradno prečiščeno besedilo, 102/07, 107/10, 87/11, 40/12 –ZUJF, 63/13 in 46/16 –ZOFVI-L. Retrieved on 25th April 2021 from http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO448

Zakon o osnovni šoli. Uradni list RS, št. 81/06 uradno prečiščeno besedilo, 102/07, 107/10, 87/11, 40/12 –ZUJF, 63/13 in 46/16 –ZOFVI-L. Retrieved on 25th April 2021 from http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO448