The relationship between shyness, willingness to communicate, and foreign language anxiety

Alenka Mikulec1, Helena Prugovečki21 University of Zagreb, Faculty of Teacher Education 2 Primary School Sesvete, Zagreb |

|

Foreign languages education and research |

Number of the paper: 72 |

Original scientific paper |

Abstract |

|

Foreign language learning (FLL) has been considered a very complex process affected by a number of factors, some of which have been identified as significant barriers to successful language learning. Among these, language anxiety has frequently been singled out as a factor that may have a negative impact on FLL. Since previous studies have confirmed connection between shyness and willingness to communicate with foreign language anxiety, this research aimed to ascertain if the relationship between those three factors would also be confirmed on the sample of preservice primary teachers. It was hypothesized that the participants who have higher results on the shyness scale and those who are less willing to communicate would report a higher level of foreign language anxiety. The participants were 71 students enrolled at the Faculty of Teacher Education University in Zagreb. The research instrument was a four-part anonymous online questionnaire used to elicit the participants' 1) general information, 2) level of shyness (the McCroskey Shyness Scale), 3) willingness to communicate (the Willingness to Communicate (WTC) Scale), and 4) foreign language anxiety (Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale). Research results showed that the majority of the participants reported low or moderate levels of anxiety, shyness, and willingness to communicate. The relationship between FL anxiety and shyness was not confirmed, but it was found that the participants who reported less willingness to communicate also reported a higher level of FL anxiety. Therefore, it is proposed that these factors should be dedicated more attention in foreign language teaching and learning at the tertiary level as well. |

|

Key words |

|

anxiety; communication; foreign language learning; preservice teachers |

Introduction

During their education, some foreign language learners may struggle and experience great discomfort, and foreign language anxiety (FLA) has been identified as one of the significant factors contributing to such feelings. It has been defined by Horwitz et al. (1986, p. 128) as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process”. MacIntyre’s (2007) definition emphasizes a person’s worry and usually negative emotions exhibited when learning or using a FL, whereas Gardner and MacIntyre (1993, p. 5) defined it as “the apprehension experienced when a situation requires the use of a second language with which the individual is not fully proficient”. Hence, it may be proposed that FLA is manifested as uncomfortable feelings such as nervousness, tension, apprehension or similar feelings observed while listening, writing, reading, or/and speaking in a foreign language. Mihaljević Djigunović (2002) mentioned four language anxiety components: 1) cognitive, which refers to a feeling of inability to perform well in a social context caused by lack of self-esteem, 2) emotional, which “implies feelings of unease, discomfort and tension” (Puškar, 2013, p. 81), 3) behavioural, manifested as “clumsiness, restraint and disturbances in gesture and speech” (Puškar, 2013, p. 81), and 4) physiological, which includes high-blood pressure, sweating, etc.

Several factors have been identified as being closely related with FLA, such as shyness, test anxiety, fear of negative evaluation (Horwitz et al., 1986) and willingness to communicate. This paper will focus on two of these – shyness and willingness to communicate. Shyness has been defined as “discomfort in social-communicative situations, a tendency to withdraw, a tendency to be timid and lack confidence, and a tendency to be quiet, neither assertive nor responsive to others”” (McCroskey & Richmond, 1982, p. 460). The same authors also propose that shyness may result from social anxiety, low social skills or low self-esteem. ). However, according to Chu (2008, pp. 12-13), even researchers are not in complete agreement on a unified definition of shyness which has been described as a form of social anxiety (Buss, 1980; Leary & Schlenker, 1981; Zimbardo, 1977), “a pattern of avoidant, reticent, and inhibited behavior” (Phillips, 1980; Pilkonis, 1977a), or as a manifestation of anxious feelings and inhibited or avoidant behavior (Cheek & Buss, 1981; Crozier, 1979; Jones & Russell, 1982). Whichever of the above explanations of shyness we choose, it has to be remembered that, in addition to the behaviours described above, shy students may also be at risk of being overlooked or being invisible by teachers and peers in the classroom (Gresham & Kern, 2004; Nilsen, 2018). Therefore, it is considered a significant factor in the classroom in general, but even more so in foreign language classrooms which are predominantly based on communication, and shy students usually refuse to speak or speak quietly or briefly.

In addition to shyness, willingness to communicate (WTC) i.e., a probability that someone will initiate communication in different social situations, has also been recognized as an important factor related to FLA. One’s willingness to communicate in L2 depends on a combination of variables such as personality, L2 self-confidence, interpersonal communication (MacIntyre et al., 1998), personal traits and a situation in which communication occurs (for instance, interlocutor’s appearance, status, a person’s feelings, conversation topic, etc.) (McCroskey, 1985). The model proposed by MacIntyre et al. (1998, p. 547) includes six categories of variables that have an impact on WTC. These categories have been divided into those representing situation-specific influences such as 1) L2 use, 2) willingness to communicate, 3) desire to communicate with a specific person and state communicative self-confidence, and the ones representing stable, enduring influences like 4) motivation and L2 self-confidence, 5) intergroup attitudes, social situation, communicative competence, and 6) social and individual context. Mihaljević Djigunović (2002) proposed that an individual analyses the social group and possible communicative outcomes, and if the group has not fulfilled the individual’s expectations, he or she may have low self-esteem and may avoid situations in which communication occurs, which may subsequently affect one’s willingness to communicate.

Finally, language proficiency has also been mentioned as a significant factor affecting FLA. It has been proposed that students who have better developed language skills have fewer negative experiences and thus their foreign language anxiety may gradually disappear (MacIntyre & Gardner, 1989; Mihaljević Djigunović, 2002).

Methods

Aim and hypotheses

The aim of this research was to establish the level of shyness, willingness to communicate, and foreign language anxiety among preservice teachers, and to find out if there is a positive or negative relationship between these three variables.

The following hypotheses were defined:

1. Students with higher results on the shyness scale will also report a higher level of foreign language anxiety.

2. Students with lower results on the willingness to communicate scale will report higher levels of foreign language anxiety.

Participants

The research participants were preservice teachers, i.e., 71 first, third, fourth, and fifth-year students of the Faculty of Teacher Education in Zagreb enrolled in two study programmes (Table 1). The average age of the participants was 22.7 years (SD = 1.1, min. 21, max. 25) and the majority were female (Table 1).The students’ average length of learning English was 11.97 years (SD = 2.45), and their average grade in English in primary school was 4.86 (SD = 0.42), whereas in secondary school it was somewhat lower at 4.59 (SD = 0.62). Most students reported not learning English outside school (n = 52) while the rest (n = 19) reported an average of 4.26 years.

Table 1. Research participants

|

Gender |

male |

n = 8, f = 11.3% |

|

female |

n = 63, f = 88.7% |

|

|

Study programme |

Primary and English/German Teacher Education (foreign language majors) |

n = 46, f = 64.8% |

|

Primary Teacher Education with modules (non-foreign language majors) |

n = 25, f = 35.2% |

|

|

Year of studies |

First |

n = 1, f =1.4% |

|

Third |

n = 20, f = 28.2% |

|

|

Fourth |

n = 13, f = 18.3% |

|

|

Fifth |

n = 37, f = 52.1% |

|

|

Exposure to English outside college more than 10 hours per week |

foreign language majors |

n = 26, f = 56.5% |

|

non-foreign language majors |

n = 3, f = 26% |

|

|

Self-assessed EFL proficiency |

foreign language majors |

M = 4.5 (SD = 0.69) |

|

non-foreign language majors |

M = 3.8 (SD = 0.71) |

All students reported some exposure to English outside college, with the majority (n = 32) reporting weekly exposure to English more than 10 hours per week, for 23 students the weekly exposure was only five hours while for the rest (n = 16) it was up to 10 hours. Differences in the exposure to English were observed when the results were compared between the foreign language majors and non-foreign language majors, with the former reporting more exposure than the latter (Table 1). Most participants seem fairly confident about their EFL proficiency, as the average self-assessed knowledge of English was 4.25 (SD = 0.77). However, here again, a difference between the foreign language majors and non-foreign language majors can be observed in favour of the former group (Table 1). As previously mentioned, language proficiency has been identified as an important factor related with FLA, therefore, the results were compared according to whether students were foreign language majors or not, following the assumption that foreign language majors are more proficient than the other group.

Results and discussion

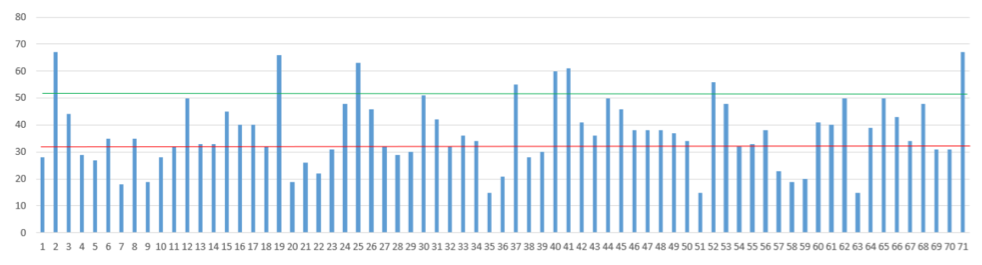

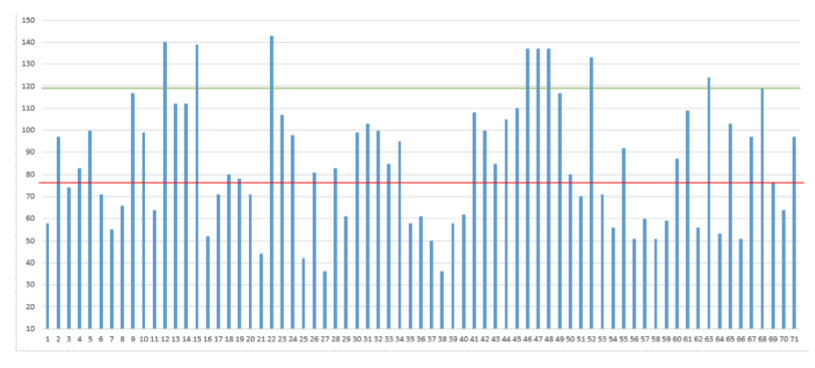

Figure 1. Students’ level of shyness

Figures 2 and 3 show the analysis of students’ levels of shyness according to their study programme.

Figure 2. The level of shyness among the foreign language majors

Based on the results, it was observed that 37% (n = 17) of the foreign language majors reported a low level of shyness compared to 24% (n = 6) of the students enrolled in the other study programme. None of the non-foreign language majors reported high levels of shyness compared to 17.4% (n = 8) of the foreign language majors. Finally, 45.6% (n = 21) of the foreign language majors reported a moderate level of shyness compared to 76% (n = 19) of the students in the other group.

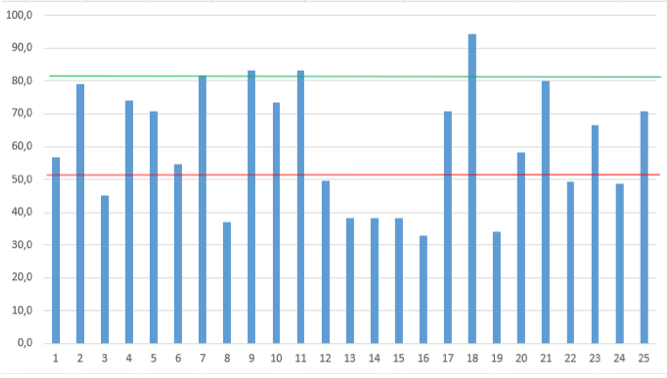

Figure 3. The level of shyness among the non-foreign language majors

The comparison of the levels of shyness according to the year of studies indicates that none of the fourth-year students reported a high level of shyness while 16.2 % (n = 6) of the fifth-year students and 10% (n = 2) of the third-year students did report a high level of shyness. The results further show that there is little difference among the students enrolled in the third, fourth, and fifth years of studies regarding their moderate (n = 11, f = 55%; n = 8, f = 61.5%; and n = 20, f = 54.1%, respectively) and low levels of shyness (n = 7, f = 35%, n = 5, f = 38.5%; and n = 11, f = 29.7%, respectively). The results of the fifth-year students are somewhat unexpected because, being in their final year of studies, they were expected to report the lowest levels of shyness. Namely, shyness has been related with environmental factors (Gard, 2000) and the fifth-year students have had the most experience in being in situations where they have had to overcome their shyness such as teaching primary school students and giving presentations in front of their colleagues, mentors, and teachers, so it was justifiably expected that they would report the lowest levels of shyness.

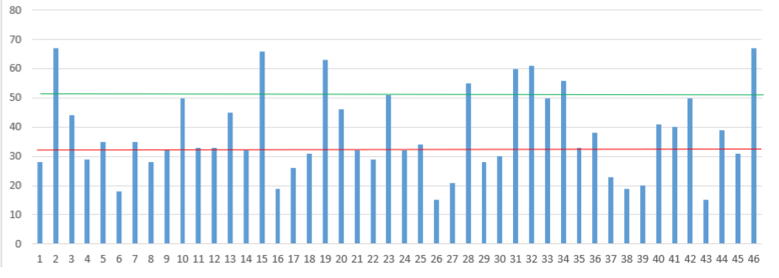

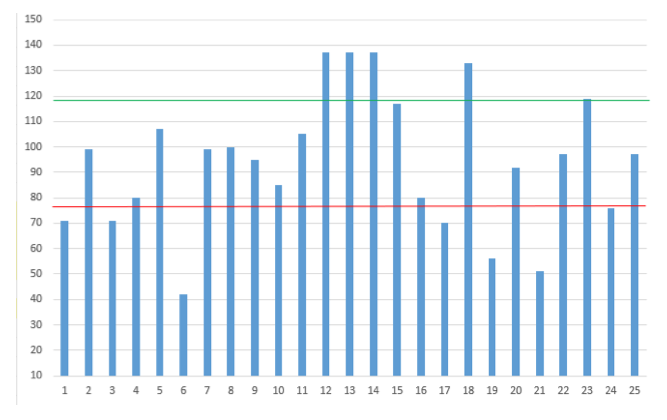

Figure 4. The level of students’ willingness to communicate

The results obtained for students’ willingness to communicate (Figure 4) show that most participants (n = 37, f = 52.1%) reported moderate, the minority (n = 8, f = 11.3%) reported a high level (scores above 82), and the rest (n = 26, f = 36.6%) reported a low level of willingness to communicate (scores below 52). The highest score was 95, reported by two students, and the lowest score was 16.3, reported by one student. Since the teaching profession requires frequent communication with students, parents, other teachers etc., it is surprising that a fairly high percentage of the participants reported moderate to low willingness to communicate.

Figure 5. The level of willingness to communicate among the foreign language majors

The analysis according to the study programme (Figures 5 and 6) has not indicated much difference between the students: 10.7% (n = 5) high, 35% (n = 16) low and 54% (n = 25) moderate willingness to communicate for foreign language majors and 12% (n = 3) high, 40% (n = 10) low and 48% (n = 12) moderate willingness to communicate for the non-foreign language majors. In both cases, the majority of the students reported moderate to low levels of willingness to communicate, with somewhat higher percentage of the non-foreign language majors reporting low levels.

Figure 6. The level of willingness to communicate among the non-foreign language majors

Analysis according to the year of studies shows that none of the fourth-year students and only few of the fifth (n = 4, f = 10.8%) and third-year (n = 4, f = 20%) students reported high levels of willingness to communicate. When their moderate and low levels of willingness to communicate are compared, little difference can be observed between the fifth (n = 14, f = 37.8% low and n = 19, f = 51.4% moderate), fourth (n = 5, f = 38.5% low and n = 8, f = 61.5% moderate), and third-year students (n = 6, F = 30% low and n = 10, f = 50% moderate). However, the results show that, somewhat surprisingly, the fewest of the youngest students (third-year students) reported the lowest level of willingness to communicate.

When the two scales (the McCroskey Shyness Scale and the Willingness to Communicate Scale) are compared, it may be observed that the majority of the participants have a moderate level of shyness (n = 40) as well as a moderate level of willingness to communicate (n = 37).

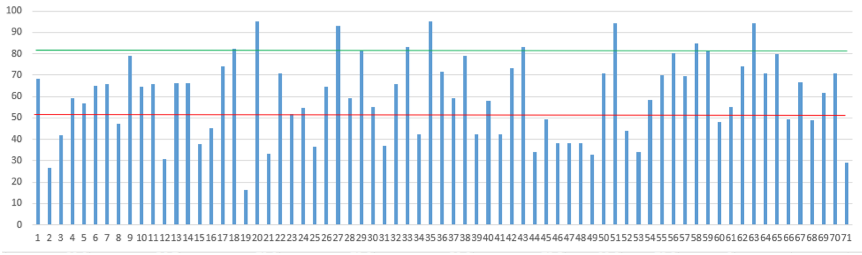

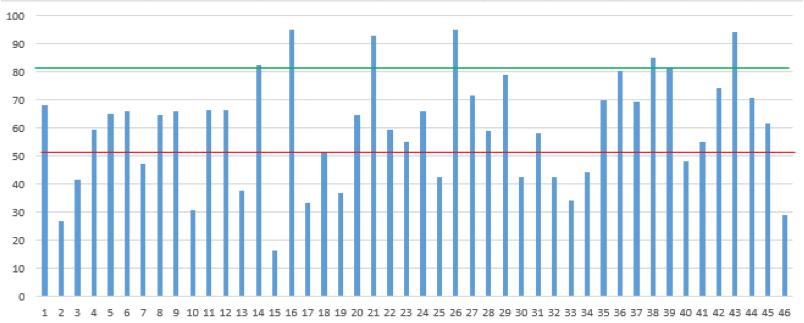

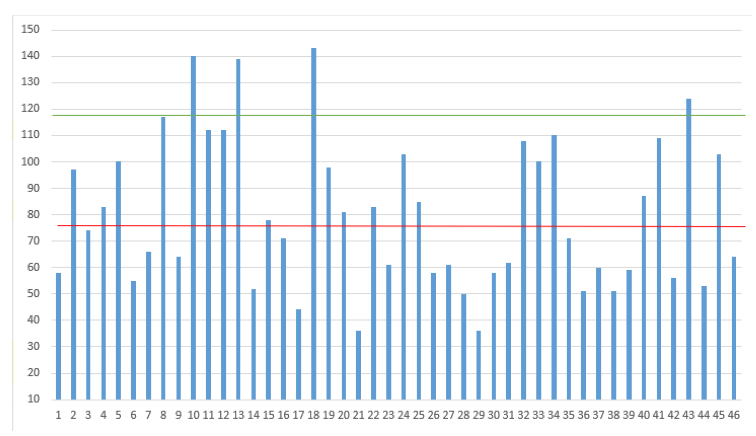

Foreign language anxiety

The results of the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (Figure 7) show that only several participants (11.3%, n = 8) reported a high level of foreign language anxiety (scores 120 or above). The number of the participants with scores lower than 76, i.e., a low level of anxiety (n = 30, f = 42.3%) or scores between 76 and 119, i.e., a moderate level of anxiety (n = 33, f = 46.5%) was similar. The highest score was 143, reported by one student, and the lowest was 36, also reported by only one student.

Figure 7. Results of the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale

Students’ foreign language anxiety level was also compared according to the study programme (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Foreign language anxiety level among the foreign language majors

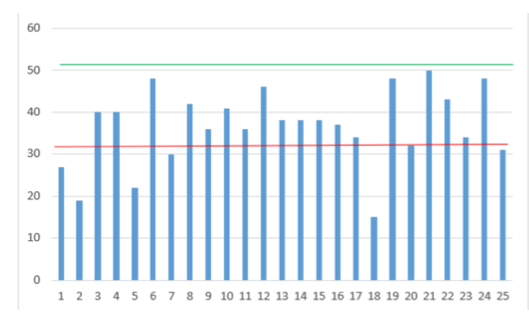

Foreign language (English/German) majors are required to listen to some lectures and study approximately four courses per semester in the foreign language. As expected, the analysis showed that only a few of the participants attending this study programme reported a high level of language anxiety (n = 4, f = 8.7%), while the majority reported low (n = 24, f = 52.2%) or moderate levels of anxiety (n = 18, f = 39.1%). On the other hand, the percentage of non-foreign language majors who reported a high level of foreign language anxiety was somewhat higher (n = 4, f = 16%). More than half of the students enrolled in this study programme reported a moderate level of language anxiety (n = 15, f = 60%) while the others (n = 6, f = 24%) indicated a low level.

Figure 9. Foreign language anxiety level among the non-foreign language majors

In order to gain a better insight into the students’ foreign language anxiety, some of the statements which most of the students disagreed with were analysed. The greatest number of students strongly disagreed with the following statements, indicating a low level of anxiety: 5. During language class, I find myself thinking about things that have nothing to do with the course (M = 1.82, n = 35); 21. The more I study for a language test, the more confused I get (M = 1.65, n = 42); 25. Language class moves so quickly I worry about getting left behind (M = 1.96, n = 35); 26. I feel more tense and nervous in my language class than in my other classes (M = 2.2, n = 31); 31. I am afraid that the other students will laugh at me when I speak the foreign language (M = 2.27, n = 32). These statements present situations or aspects which mostly do not cause problems for the participants while learning and using a foreign language.

In order to gain a better insight into the students’ foreign language anxiety, some of the statements which most of the students disagreed with were analysed. The greatest number of students strongly disagreed with the following statements, indicating a low level of anxiety: 5.

During language class, I find myself thinking about things that have nothing to do with the course The more I study for a language test, the more confused I get Language class moves so quickly I worry about getting left behind I feel more tense and nervous in my language class than in my other classes

(M = 2.2, n = 31); 31. I am afraid that the other students will laugh at me when I speak the foreign language (M = 2.27, n = 32). These statements present situations or aspects which mostly do not cause problems for the participants while learning and using a foreign language.

Correlations between FLA, shyness and willingness to communicate

One of the objectives of the research was to ascertain if there was a correlation between the three studied variables. Spearman’s rho test was used in the analysis of a possible correlation between shyness and foreign language anxiety, and the result indicated no correlation between the two variables (Table 2). That is to say, the students who reported higher level of shyness did not report experiencing higher level of foreign language anxiety. These results are not in accordance with those obtained by Ordulj and Grabar (2014), who found that Croatian students learning Italian in foreign language schools did experience foreign language anxiety, and that although the level and years of learning were not related with anxiety, the level of foreign language anxiety was found to be higher among shy students. The authors proposed that the possible explanation of such results may be because “quite often there is teasing or making fun of a person who pronounces the word wrongly, applies rules in a wrong way, or finds it hard to answer a question using adequate words” (Ordulj & Grabar, 2014, p. 219). On the other hand, the results in this study are similar to those presented by Bashosh et al. (2013), who also found no significant relationship between shyness and foreign language anxiety among 60 undergraduates learning English as a foreign language in Iran.

Table 2. Correlations between willingness to communicate, shyness and FLA

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Spearman’s rho test was also used to establish if there is a correlation between willingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. The results confirmed a statistically significant correlation between the two variables (Table 2) indicating that the students who reported a high level of willingness to communicate, also reported a low level of foreign language anxiety while the students with a low level of willingness to communicate reported a high level of language anxiety. These results are in contrast with those obtained by Mihaljević Djigunović (2004), who found no relationship between the two variables. On the other hand, Manipuspika (2018) and MacIntyre and Charos (1996) did report correlation between willingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety.

Conclusion

The analysis of the results obtained with the shyness scale showed that the majority of the participants reported a moderate, and only a few reported a high level of shyness. In addition, it was found that the foreign language majors reported somewhat higher levels of shyness than the non-foreign language majors and that, somewhat unexpectedly, the fifth-year students reported higher level of shyness than the students in the lower years of studies.

The results of the scale measuring the students’ willingness to communicate were also rather unexpected considering that only a minority of the participants reported they would initiate communication in every situation, which is not really in accordance with the nature of the teaching profession. Moreover, similar levels of willingness to communicate were reported regardless of the participants’ study programme or the year of studies.

The third questionnaire, which measured foreign language anxiety among the students, yielded results indicating a moderate or a low level of foreign language anxiety. Foreign language majors mainly reported a low level of FLA, whereas most of the non-foreign language majors reported a moderate level of FLA. These results are not very surprising since the foreign language majors are exposed to the foreign language significantly more and on a regular basis which, according to Mihaljević Djigunović and Legac (2009), may prevent and reduce FLA.

The results of the research confirmed one of the proposed hypotheses, i.e., the students who reported less willingness to communicate also reported a higher level of language anxiety than the participants whose willingness to communicate was higher. The hypothesis testing a possible correlation between the students’ shyness and their level of foreign language anxiety was not confirmed. A possible explanation might be that, in the present sample, only a very small number of participants reported experiencing a high level of shyness.

Finally, the fact that the sample size was small and that it was a convenience sample has to be mentioned as one of the limitations of this research. In addition, since some of the results were unexpected and could not be explained based on the obtained data, future studies might also consider the following: factors causing shyness, establishing whether shyness is related to one of the language skills, investigating additional variables affecting learners’ WTC such as factors proposed in McIntyre et al.’ s model (L2 use, self-confidence, motivation, etc.), considering positive and negative reactions to anxiety (Matić, 2021), etc. In addition, since the data collected in this research were self-report measures, structured observation and some additional objective measures might be applied in future studies.

Implications

Although FLA may pose a barrier to learning and using a FL, there are certain activities both teachers and learners may use in order to reduce anxiety and increase the learners’ confidence. Tsiplakides and Keramida (2009) propose that in the classroom, students should be given control over project work because then they are not passive, and they use a foreign language in a meaningful context. It has also been proposed that teachers play a significant role in reducing FLA in the classroom, i.e., they need to establish a supportive classroom atmosphere to allow students to freely ask questions and make mistakes without any consequences and they need to ensure that students’ grades and scores are their private feedback and are not shared in front of everyone. Other activities that may help reduce anxiety are for students to write examples of language mistakes which occur and discuss them in terms of logical thinking, humour, originality etc., writing a learning diary in which students could describe their feelings about a certain aspect of language learning or writing letters about their learning issues, discussing them and replying to their peers who have anxiety in order to raise students’ awareness that they are not alone and that other students may have similar feelings towards learning a foreign language (Mihaljević Djigunović, 2002). Horwitz et al. (1986, p. 131) suggested “relaxation exercises, advice on effective language learning strategies, behavioral contracting, and journal keeping.”

To sum up, in addition to helping students reduce their foreign language anxiety, teachers should also be aware of aspects contributing to these feelings and try to control them, e.g., since reiterating negative experiences due to failures, for instance, in a FL classroom may contribute to increased FLA (MacIntyre & Gardner, 1989), the teacher may, at least occasionally, structure the lesson and activities so as to provide the learners with opportunities to complete them successfully.

References

Bashosh, S., Abbas Nejad, M., Rastegar, M., & Marzban, A. (2013). The Relationship between Shyness, Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety, Willingness to Communicate, Gender, and EFL Proficiency. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(11), 2098–2106.

Chu, H. N. R. (2008). Shyness and EFL Learning in Taiwan: A Study of Shy and Non-shy College Students’ Use of Strategies, Foreign Language Anxiety, Motivation, and Willingness to Communicate. Doctoral dissertation. Austin: University of Texas.

Gard, C. (2000). How to overcomes shyness. Current Health, 27(1), 28-30.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1993). A student’s contribution to second-language learning. Part II: Affective variables. Language Teaching, 26, 1–11.

Gresham, F. M., & Kern, L. (2004). Internalizing Behavior Problems in Children and Adolescents. In R. B. Rutherford, M. M. Quinn, & S. R. Mathur (Eds.), Handbook of research in emotional and behavioral disorders (pp. 262–281). The Guilford Press.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132.

Kent, H., & Fisher, D. (1997). Associations between teacher personality and classroom environment. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 407395). Retrieved on 4th April, 2022 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED407395.pdf

MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to Communicate in the Second Language: Understanding the Decision to Speak as a Volitional Process. The Modern Language Journal, 91(4), 564–576.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Charos, C. (1996). Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 15(1), 3–26.

MacIntyre, P., Clement, R., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation. Modern Language Journal, 82, 545–562.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1989). Anxiety and Second-Language Learning: Toward a Theoretical Clarification. Language Learning, 39(2), 251–275.

Manipuspika, Y. S. (2018). Correlation between Anxiety and Willingness to Communicate in the Indonesian EFL Context. Arab World English Journal, 9(2). doi: 10.24093/awej/vol9no2.14

Matić, I. (2021). Strah od čitanja na njemačkome kao stranome jeziku u izvornih govornika hrvatskoga jezika. Doctoral dissertation. Zagreb: University of Zagreb.

McCroskey, J. C. (1985). Willingness to Communicate: The Construct and its Measurement. The Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association, 71, 3–11.

McCroskey, J. C., & Baer, J. E. (1985). Willingness to Communicate: The Construct and Its

Measurement. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1987). Willingness to communicate. In J.C. McCroskey, & J.A.

Daly (Eds.), Personality and Interpersonal Communication (pp. 129–156). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1982). Communication apprehension and shyness: conceptual

and operational distinctions. Central State Speech Journal, 458–468.

McCutcheon, J. W., Schmidt, C.P., & Bolden, S. H. (1997). Relationships among selected personality

variables, academic achievement and student teaching behavior. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 24(3), 38–44.

McWilliams, S. E. (2019). Teacher Shyness and Self-Efficacy When Working with Shy Children in Early

Childhood Education: A Mixed Methods Study. Doctoral Dissertation. Lincoln; University of Nebraska.

Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2004). Beyond Language Anxiety. SRAZ, XLIX, 201–212.

Mihaljević Djigunović, J. (2002). Strah od stranoga jezika. Zagreb: Naklada Ljevak.

Mihaljević Djigunović, J., & Legac, V. (2009). Foreign Language Anxiety and Listening Comprehension of Monolingual and Bilingual EFL Learners. SRAZ, LIII, 327–347.

Nilsen, S. (2018). Inside but still on the outside? Teachers' experiences with the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs in general education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1e17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1503348

Ordulj, A., & Grabar, I. (2014). Shyness and Foreign Language Anxiety. 2nd International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, 215-227.

Puškar, K. (2013). Who’s Afraid of Language Still?. In J. Dombi, J. Horváth, & M. Nikolov (Eds.), UPRT 2013: Empirical Studies in English Applied Linguistics (pp. 80–95). Lingua Franca Csoport.

Roy, D. D. (1995). Differences in personality of experienced teachers, physicians, bank managers and fine artists. Psychological Studies, 40(1), 51–56.

Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2009). Helping Students Overcome Foreign Language Speaking Anxiety in the English Classroom: Theoretical Issues and Practical Recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39–44.

Vorkapic, S. T. (2012). The significance of preschool teacher’s personality in early childhood education: Analysis of Eysenck’s and big five dimensions of personality. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 28–37.

| 2. međunarodna znanstvena i umjetnička konferencija Učiteljskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Suvremene teme u odgoju i obrazovanju – STOO2 - in memoriam prof. emer. dr. sc. Milanu Matijeviću, Zagreb, Hrvatska |

Odnos između straha od stranoga jezika, spremnosti na komunikaciju i sramežljivosti

Sažetak |

|

Učenje stranih jezika smatra se vrlo složenim procesom na koji utječe niz čimbenika, od kojih su neki prepoznati kao značajne prepreke uspješnom učenju jezika. Među njima se strah od jezika često izdvaja kao čimbenik koji može imati negativan utjecaj na učenje stranih jezika. Budući da je prethodnim istraživanjima potvrđena povezanost sramežljivosti i spremnosti na komunikaciju sa strahom od stranoga jezika, ovo je istraživanje imalo za cilj utvrditi postoji li veza između tri navedena čimbenika i među budućim učiteljima. U istraživanju se krenulo od pretpostavke da će sudionici koji imaju više rezultate na ljestvici sramežljivosti i oni koji su manje spremni na komunikaciju osjećati veći strah od stranoga jezika. U istraživanju su sudjelovali 71 student i studentica Učiteljskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. Instrument korišten u istraživanju bio je četverodijelni anonimni online upitnik kojim su prikupljeni sljedeći podatci o sudionicima 1) opće informacije, 2) razina sramežljivosti (McCroskeyjeva skala sramežljivosti), 3) spremnost na komunikaciju (Skala spremnosti na komunikaciju), i 4) strah od stranoga jezika (Skala straha od stranoga jezika u učionici). Rezultati istraživanja pokazali su da većina sudionika osjeća nisku ili umjerenu razinu straha od stranoga jezika, sramežljivosti i spremnosti na komunikaciju. Povezanost između straha od stranoga jezika i sramežljivosti nije potvrđena, ali je utvrđeno da ispitanici koji smatraju da su manje spremni na komunikaciju na materinskom jeziku osjećaju izraženiji strah od stranoga jezika. Stoga se predlaže da se navedenim čimbenicima posveti više pažnje u poučavanju i učenju stranih jezika i na višim razinama obrazovanja. |

|

Ključne riječi |

|

budući učitelji; komunikacija; strah; učenje stranih jezika |